My Sergei (29 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

The closest thing we have to a Russian Thanksgiving is in February, the middle of winter, when we celebrate something called

Butter Holiday, just prior to a religious fast. It’s a week-long holiday in which the purpose, like Thanksgiving, is to eat

as much as you can. On Butter Holiday, though, Russians serve blini, which are Russian pancakes. They fill them with caviar,

or sausage, or sour cream, then fill them with jam for dessert. Unfortunately, I don’t particularly like to eat blini, so

this is not one of my favorite feasts.

Irene Ersek

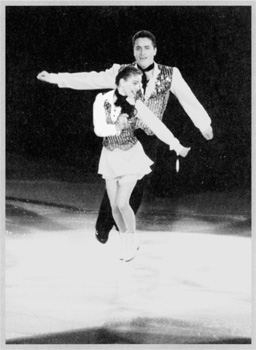

Skating to Gershwin’s “Crazy for You.”

In December, Sergei and I won the World Professional Championships for the third time, skating a Gershwin program as our technical

number and the Rodin number as our artistic one. My mother went home to celebrate Christmas with my father and sister, and

Daria stayed with us in Simsbury. The tour opened in Boston Garden on December 27, and we had no choice but to bring Daria

to the rehearsal there the day before. Debbie said she’d watch Daria for us. But dear Dasha, who was two, was scared of Debbie.

It was terrible. Every time we tried to rehearse something, she started screaming. Debbie was so distraught. She kept saying,

I came to help you, and I can’t. We’d put Dasha down in a chair beside the ice and tell her, “Look, Mommy and Daddy are going

to skate right there. You sit and watch, okay?” But as soon as the music started again, she’d begin screaming like someone

was torturing her. Sandra Bezic, the director of the show, tried to calm her. Michael Seibert, Sandra’s associate choreographer,

tried to calm her. But nothing worked. Sergei finally had to lift her in his arms and skate with her the whole rehearsal.

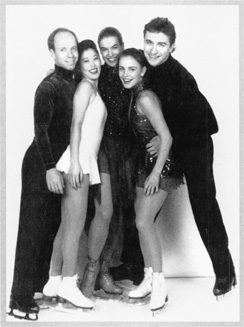

Heinz Kluetmeier

With the cast of Stars on Ice.

After that ordeal we called my mother in Moscow. Mom? How was your Christmas? When are you coming back? Not tomorrow? Why

not? Here’s a ticket we bought for you.

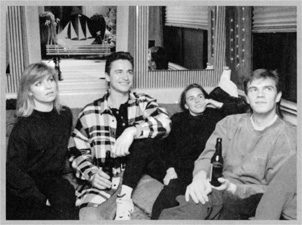

Peter Bregg

On the Stars on Ice tour bus.

The tour—forty-seven cities from Portland, Oregon, to Portland, Maine, over the next three months—was great fun. The luggage

traveled everywhere by bus, and we had our choice of whether to go with the luggage or fly. The bus rides themselves were

quite comfortable. The driver always had homemade soup for us, and there was a refrigerator stocked with cold beer, a coffee

maker, two televisions, and a dozen or so sleeping bunks. For the first time there were four other Russians in Stars on Ice,

Elena Bechke and Denis Petrov and ice dancers Natalia Annenko and Genrikh Sretenski. The six of us usually sat together in

one of the booths in the back, which the North American skaters started calling the Russia Room. Kurt Browning and Scott Hamilton

used to come back and ask, “Can I have a seat in the Russia Room, please?” Kurt, in fact, gave us a poster of the Russian

Tea Room in New York to hang on the wall back there.

A lot of the arenas we skated in were ones we’d performed in before, and what amazed me was that Sergei remembered everybody.

We’d be standing beside the ice, and he’d say, “That’s the same Zamboni driver as last year.” Or he’d remember the dressing

room attendants or the security guards. Sometimes even individual fans. For me, I don’t even see these people. But Sergei

was the absolute opposite of a snob. In fact, I think he’d have preferred to spend an evening with these people than in the

company, even, of skaters.

What he disliked were the receptions afterward, when the fancy people would come up and whisper, so the other skaters wouldn’t

hear, “I think you were the best.” Sergei hated flattery. That was the worst for him.

This tour finally ended in April. Back home in Simsbury, we were so exhausted from the season that all we wanted to do was

relax. It was spring, and all the flowers were out. We sat out on the porch and had long breakfasts every day, and Sergei

would feed bread to the squirrels. It was so nice not to rush, not to have to put anything in a suitcase. We didn’t watch

anything. We watched only each other, and Daria.

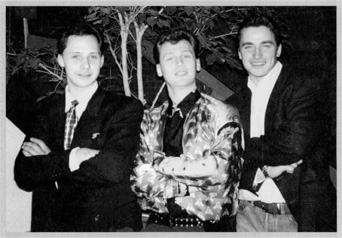

At home in Simsbury with our neighbors Vladimir and Victor Petrenko.

We had one more exhibition in Lausanne, Switzerland. The weather was beautiful, and Sergei and I walked around town holding

hands. It was a weekday, yet all the people were walking outside, enjoying the sunshine. It looked like a Sunday. We talked

about how great that was, how these people didn’t live to work. How they hadn’t forgotten they had just one life to live.

You go to Europe, and your eyes just relax from the beauty around you, and you see the people having wine with their lunch

in the sun, and you wonder, Is every day here a holiday? In America, people go to the gym instead of having lunch.

We talked about how the villages in Russia, like the one where Yegor lived on the Volga River, were also like this. If it’s

a nice day, maybe the people skip work. They don’t care that it’s a day they don’t put another dollar in their pocket. And

this was Sergei’s nature, too.

F

or my twenty-fourth birthday Sergei drove me to

New York—to drive in a car with Sergei was still my favorite thing to do—and he bought me a Louis Vuitton handbag. Then,

just when I thought it was another year without a surprise, the next morning he made me breakfast in bed.

This was my dream. I had mentioned it to Lynn Plage when she asked me for the Stars on Ice program what my perfect day would

be. I told her it would begin with Sergei making me breakfast in bed. This was quite a fantasy, since Sergei didn’t even know

how to make coffee. But Scott Hamilton found out from Lynn what I had said, and he made Sergei promise to fulfill my dream.

Scott told me that Sergei had given him this promise, so I began to tease him a little.

“Serioque, are you going to make me breakfast in bed sometime?”

“Yes, yes. But first I have to watch you do it.” He asked me how to work the coffee maker, and I showed him. I think he already

knew how to work the toaster.

Then the morning after my birthday, after staying up very late, he crept out of bed while I was sleeping. He had to make the

coffee twice, because the first time it didn’t work—I don’t know what he did wrong. He poured the orange juice and made

the toast. Then he got the idea to add flowers. He had to drive to the grocery store to get them, and he was so worried that

he’d wake me when starting the car, ruining the surprise, that he pushed the car out of the garage first. Then he brought

me all these things on a tray, and I was so, so surprised. I made him take a picture of me with this breakfast.

Sergei’s back had been seriously bothering him. He’d done something to it just after the Olympics while practicing a death

spiral, then had hurt it again while doing the Rodin number. Just before my birthday, he had reinjured it in the gym. We thought

it was some sort of a slipped disc that was pinching a nerve, because when it happened it sent pain shooting all the way down

to his toes. In fact, he was losing the feeling in the toes of his left foot.

It was bothering him too much to practice. Still, Marina came to Simsbury in late May so we could begin working on our new

program. She’d selected music from Grieg’s Second Symphony, Concert in A minor, and the theme was that I was a weak person,

and Sergei must lift me up and get me going. If I lose my energy and lie on the ice, Sergei will give me second life and give

me power.

Marina always saw music in terms of either color or weather or seasons. This Grieg music she saw in waves, first very high,

then very low. The high waves would be for the lifts. Then when the music fell low I would go around Sergei and lie down on

the ice. Sergei would lay his hand on me and ask me to stand up. Marina would tell him, “You have the perfect warm hand; your

hand should give her life.” The music was almost like broken glass, much colder than the Rachmaninoff music that accompanied

the Rodin program.

Sergei began seeing a wide array of doctors about his back. In Moscow, one doctor told him it was probably caused by air-conditioning

from driving in the car. So we stopped using the air-conditioning. Still, his back continued to get worse. Sergei had problems

even getting his foot into his skate boot because he couldn’t straighten his toes. He couldn’t skate. He took one step onto

the ice, and he didn’t feel his foot at all.

We went to see Dr. Abrams in Princeton. He had fixed the rotator cuff injury in Sergei’s shoulder. After a series of tests

confirmed that one of Sergei’s discs in his back was quite swollen, Dr. Abrams told us it was a serious problem that might

require surgery. We didn’t like that idea at all.

We talked to Galina Zmievskaya, who knew a chiropractor in Odessa, in Ukraine, who had fixed a similar problem with Viktor

Petrenko’s back. She made us an appointment, and we flew immediately to Moscow. I stayed with my parents and Daria at our

dacha, while Sergei bought a ticket to fly to Odessa to see Viktor’s chiropractor. They sold him the ticket, no problem, but

when he went to the plane, they told Sergei they had no more seats. But if you’d like to stand? So he stood the whole flight

to Odessa in the place where the stewardesses work. Unbelievable.

The next day he went to the chiropractor, and this man began working on his back, rearranging things in the most agonizing

fashion. Sergei couldn’t even walk the next day. The doctor told him not even to try, just to lie down all day. “It’s almost

mini-surgery I did for you,” the man said.

He worked on him one more time, two days later, then we flew back to the States. We started skating slowly—one day on, one

day off. But Sergei still couldn’t feel his foot on the ice. So we went to see Dr. Abrams again in Princeton, and he told

us now that surgery might not be necessary. First he wanted to do more tests, one of which involved taking fluid out of Sergei’s

spine with a long needle. It made me crazy to even think about it. I was trying to talk to Sergei, to make him feel calm about

the procedure, when I almost passed out. Sergei took one look at me and said, “Katia, what’s going on with you?”

I felt like I had to sit or I’d faint. I didn’t watch as they took the fluid out, but afterward Sergei felt so terrible they

made him lie down for two hours before we could drive home. Sergei was never rude to me, ever. But this time I tried to ask

him how he felt, and he was so mad about his back, so frustrated with the doctors and uncomfortable with the pain, that he

didn’t talk to me. I was almost afraid to ask him anything. He was reading his book and wouldn’t even look at me.