My Sergei (28 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

I was proud of myself for skating clean, landing both double axels after struggling with them for the last three years. Sergei,

I could see, wasn’t happy. Gold medal or not, he was not used to making mistakes. Still, his many friends on the speed-skating

team brought a smile to his lips as they screamed for him as we accepted our medals. I thought the audience clapped more for

Artur and Natalia than for us, which upset me a little bit.

But there were certainly no hard feelings between us, and we went back to the house and celebrated together for the next three

days. Artur knew he and Natalia had skated their best, and Sergei was the type of man who could beat you but afterward you

still wanted to go have a beer with him. He and Artur talked all the time the rest of the Olympics, and because they’re friends,

they could share their opinions about each other, and their skating, very easily. Natalia and I weren’t like this. But we

did go skiing together three times in Lillehammer. It was only my third time on snow skis, and I started at the very, very

small hill, like the little kids. Then I went with Natalia and Sergei to the bigger hill, and Natalia, who loves speed, left

me because I was falling down so often. Sergei was waiting for me all the time. “Serioque? Are you down there? I’m coming.”

It was fun.

The day after we won, we were invited to a party at the Russia House, a hospitality center for Russian visitors in Lillehammer,

to celebrate. We were driving with Evgenia Shishkova and Vadim Naumov, the Russian pairs team who had finished fourth, and

a month later won the World Championships. Naumov said to Sergei, “So, what was the reason you came back? Just to win another

gold medal? You didn’t improve. We could have won the bronze if you’d stayed professional.”

Sergei didn’t say anything in return. What can you say to a person with such a mentality? We have an expression in Russia:

After the fighting is over, don’t swing your fists.

We originally thought we would also go on to the World Championships in Chiba, Japan, but we were so relaxed after the Olymics,

we decided not to. This gold medal in 1994 satisfied me in a way no other medal I’d won ever had, even though we had made

this one mistake. I knew how hard we’d worked and how well we’d skated the whole year. I knew how much we’d sacrificed personally,

spending that time away from Daria. And I was satisfied it had been worth it. The first gold medal we had won for the Soviet

Union. This one we won for each other.

S

hortly after the Olympics,

People

magazine took a picture

of me for their issue naming the “50 Most Beautiful People in the World.” I didn’t like it when someone asked me to be in

a photo shoot, and not Sergei. I always thought, we’re a pair. We should be together in the magazines. But that didn’t stop

me from modeling for

People

for five hours. I asked Sergei if he wanted to come along to watch, but he told me to go ahead by myself. The photographer

had rented a suite at the Metropole in Moscow for the shoot, the same suite that Michael Jackson stayed in when he visited

the city. It even had a sauna in it. We changed dresses, chose costumes, put on jewelry, took off jewelry, carried skates,

took off skates. I did my own makeup. It was fun.

I didn’t realize how big a deal it was until the issue came out. We were on tour in the United States with Tom Collins’s World

and Olympic champions, and I remember being so proud until Marina Klimova showed me the magazine and said, “They made a bad

picture of you.”

“Maybe next time they’ll do a better job,” I said.

Then I showed the magazine to Sergei and asked him if he liked it.

He said, “Oh, it’s nice. But it’s not with me.”

Now I started to get upset about it. Lynn Plage gave me a big framed picture of the magazine photo, but by then I couldn’t

look at it without feeling badly, so I sent it to Moscow. My parents still have this picture hanging in their apartment, so

at least my mom and dad appreciated it.

There were thirteen Russians on Tommy’s tour that spring, more than ever before, which was great fun for us. We performed

in sixty-five cities, and during the last month Daria and my mom traveled with us. For some reason, Daria was afraid of all

men. As soon as she’d see Tom, she’d start to cry. But besides that, she was a good little traveler.

Tom wanted to give us a contract for the next three years, but he said he would have to pay us less per show than he was paying

us now. I talked to Jay Ogden at IMG, and he offered us a four-year deal for a little more money to skate in Stars on Ice.

It wasn’t as much as we’d heard some of the other gold medalists were making, or even as much as some silver medalists, if

they were American. Russian skaters, we’d been told, were never paid the same as North Americans. But I didn’t think I could

ask Oksana or Viktor or Scott—even the closest friends—how much they were making. I just couldn’t. All the time, we were

thinking that we’re being taken advantage of by the agents. They knew much more than we did, and they spoke their own language.

Not only the English language, which is how the contracts were written, but the legal language. It gives me a headache to

even look at these contracts. But what could we do? We ended up signing for what Jay suggested, and were happy with it. There

was nothing in our background to prepare Sergei and me for contract negotiations.

While we were on this tour, Bob Young came and talked to us about training in the new facility that he was managing in Simsbury,

Connecticut. We’d seen Bob a few times with the American teams, coaching pairs, and he told us that Viktor, Oksana, and Galina

Zmievskaya were all moving to Simsbury to train at this International Skating Center.

Ever since Daria was born, we knew that if we were going to make a living as professional skaters, we’d have to move to the

United States. There was nowhere for us to work in Russia. We could coach there, but for what salary? To get a five-room apartment

in Moscow, which we’d looked into, cost as much as our house in Florida, and certainly not less than a hundred thousand dollars.

We told Bob Young to talk to Jay Ogden about it, and Jay made a deal with him that in return for doing two shows a year at

this new facility, we could have a free condominium in Simsbury to live in, and free ice time. It made much more sense for

us to do this, and live near other Russian friends, than to move to the home we’d bought in Tampa.

In mid-August we decided to visit this Simsbury facility and see what this condominium looked like. We told our parents that

we were going, but we didn’t know where we were going. We weren’t thinking of it as a permanent move. We flew to New York,

drove the two hours to Simsbury, and when we saw the condominium Bob had arranged for us, we fell in love with it right away.

We liked the nearness to New York and the small-town feeling of Simsbury. Debbie Nast, who worked with Jay at IMG, had gotten

us a bed, a coffee maker, towels, and sheets. Bob gave us a television and telephone. And those were the only pieces of furniture

we had in this condominium for the first six months. It felt like a place for a honeymoon, for making a little nest.

Then Bob took us to see the place where the rink was to be built. They hadn’t even poured the cement yet. It was just sand

and boards. He showed us the plans, but we were laughing, figuring we wouldn’t be staying in this great condominium for long.

It was just a wonderful dream. The way they build buildings in Moscow, we were sure it would be another five years before

Simsbury had its training center.

But by October it was finished. My mom came over with Daria, and for the first time in our lives, Sergei and I felt like we

had our own home. Daria had a bedroom of her own, which Sergei had wallpapered by himself as a surprise to both of us. He

set up her bed and hung the pictures and mirror on the wall, all of it very professionally. It was the first time he’d ever

done anything like that with his hands, and he enjoyed it. He was good at it. Sergei generally believed that if you were going

to do something, you might as well excel at it or not get started at all. His father had been quite a carpenter. He had built

their dacha outside Moscow by himself, driving up every weekend to work on this dacha alone. It gave me reason to think maybe

someday Sergei would build a house for me.

• • •

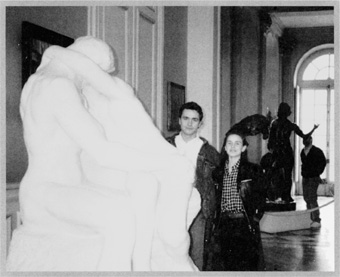

That summer Marina created a new program for us which we began to refer to as “the Rodin number.” This was my favorite exhibition

program. Every night it was like a new story to tell.

It was set to the music of Rachmaninoff, who was one of Marina’s favorite composers, and the program was based on the sculptures

of Auguste Rodin. I don’t know where Marina got this idea, but she gave us a book of Rodin’s sculptures, which we’d bring

to the ice rink. Then Sergei and I would try to copy some of the poses in the book.

It was unbelievably difficult, because most of the sculptures were of people in fantastic positions. They weren’t merely standing.

Some looked as if they were weightlessly reaching out in the sky, and we had to try to reenact these poses while skating.

It was all new, different, hard, but also quite interesting. We tried even to mimic the way he had sculpted a pair of hands,

intertwined. In one part I had to come around the back of Sergei, which I’d never done before on the ice. He was always the

one holding me in front of him. At the end of the program, Sergei lay on the ice, pulled his knees up, and I lay on his knees

on my back. Then I threw my head back to look into his eyes.

In the Rodin Museum in Paris with the statue that inspired my favorite program.

All the poses were about love, pure and unspoiled. The idea of this program was to show how love is beautiful, how a man and

woman’s body are beautiful. For costumes, we first considered tan bodysuits, so we’d look like nude statues, because many

of Rodin’s sculptures are erotic. Not pornographic, but erotic in a natural way. But we settled on a very simple, wraparound

skirt for me, tan colored, and rust-colored pants and T-shirt for Sergei. They showed the beauty of the body and the beauty

of the forms we were making on the ice. Essentially, we were skating as moving artworks.

Marina wanted this number to be entitled “The Kiss,” because that was the name of her favorite sculpture, and the one we posed

as at the beginning. We didn’t actually kiss, but we almost did. What I found magical about this program was that every time

we skated it, it was different. One day I could touch Sergei here, touch him there; the next day I could touch him someplace

different. Marina only said to me, “In this part, make him warm.” She said to Sergei, “Feel her touch. Show us that you feel

it.”

I never got tired of skating this program. Although it was too difficult to be sensual for us, we continued to get new feelings

from it throughout the year, and we continued to improve it. We started working on it in August 1994, and I think we skated

our best performance in April 1995. Every night I heard the music as if for the first time. That was the magic.

• • •

My grandfather, Diaka, died in September 1994. I still think of this gentle man whenever I see mushrooms growing in the wild,

and I hope I am able to teach Daria the things he taught me. Soon after this, on my mother’s birthday, Veld, our Great Dane,

also died. Our string of bad luck had begun.

Sergei and I traveled so much that fall that we never even had a week in our condominium. Always, another exhibition or competition.

But it was great to feel we could come back to our own house, to go to work then return and see our baby. We couldn’t wish

for anything better.

We spent a month in Lake Placid in the fall rehearsing for that year’s Stars on Ice, but this time Debbie Nast helped get

us a condominium. So Daria and Mom were also with us. The whole cast, which we thought of as our extended family, got together

for a big Thanksgiving dinner, which is a holiday we don’t have in Russia. We don’t have turkey in Russia, or sweet potatoes,

or cranberry sauce—my favorite—so for us this Thanksgiving dinner was fairly exotic.