My Sergei (12 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

So while the other skaters flew off to America, Sergei and I went back to Moscow. Life there hadn’t changed appreciably for

us as a result of our Olympic gold medal. We were a little more recognizable perhaps, but I didn’t feel like a celebrity at

home. Moscow was so big and busy, and a lot of successful athletes were living there. Our friends still treated us the same.

But I got a big surprise when my parents took me on a two-week vacation to the Black Sea. While there, I got a call from our

state department inviting me to a dinner that President Mikhail Gorbachev was holding for President Ronald Reagan.

It was exciting, and I just assumed Sergei would be invited too. I thought it would be fun to be there with him, so I rushed

back to Moscow, and when I got in I gave Sergei a call. He told me he hadn’t been invited to the banquet, but that I should

go ahead and attend it alone. I didn’t know what I should do. I went, but without Sergei there, or any other friends, I was

very bored. I was put at a table with President Reagan, and Raisa Gorbachev was seated beside me. But she didn’t talk to me,

and I didn’t have a very good time.

When I went back to my apartment, I discovered that while I’d been at the Black Sea resort, Sergei had brought me flowers

and perfume for my seventeenth birthday. I hadn’t told him that I was going to be away. So Sergei had left these gifts with

my grandmother, who was almost as excited about them as I was. “Look what Sergei brought you!” She was crazy about Sergei

and used to ask me to bring him home for lunch after practice all the time. “Why don’t you bring Sergei?” she would say. “I

made him his favorite, meatloaf.” I sent him a telegram thanking him for the birthday presents. I don’t remember why I didn’t

call him. I think maybe he wasn’t home.

I didn’t see him for two more weeks, then we met up at a training camp on the Baltic Sea in Jurmala. He looked as if he’d

lost weight, and when I looked at him more closely, I saw that he had scars on his arms, with stitches. “What’s this?” I asked

him, frightened.

He wouldn’t tell me. He said, “It’s not important for you to know.” All I ever learned was that it was some sort of fight.

He never talked about such things with me. Or when he was in pain. Or anything bad. It was like he didn’t think I should hear

about that side of life.

I was growing then, maturing physically. I’d gained a couple of inches in height, so I was now almost five feet two inches

tall and weighed ninety-five pounds. My thinking was changing, too, about everything. Absolutely everything. My mom told me

it was because of my age, that all girls underwent such changes as their bodies matured, but I still couldn’t get used to

all these changes and new feelings.

I wrote in my journal that my own nature was driving me crazy. I began being rude to Leonovich, who I now believed wasn’t

training us hard enough. Sergei would tell me, “Katuuh, he’s trying to make us happy in the practice. He’s okay.” But I wouldn’t

listen. Because of the changes in my body, I was having trouble landing my jumps. It was like I had to learn everything over

again. And then Leonovich would come to the practice and say something like, “Okay, do what you feel like doing this practice.

Listen to how your legs are feeling.” And I’d get furious, telling Sergei, “He’s the coach. He has to tell us what we’re supposed

to do.”

Then I’d get mad at myself for behaving badly to him, and the next day I’d wonder if I was behaving badly or not. Everything

I did, I had two opinions about. And I’d try to correct my mood swings. If I was sad, I’d try to make myself happy, which

of course I couldn’t do.

I didn’t have anyone to talk to about these things, except the other half of my Gemini personality. I couldn’t talk about

it with my sister, who was four years younger than me, or my mother, because I was so often away from home. Or with Anna,

who was not that type of friend. So I had no one. I was always keeping my thoughts to myself.

But when I told Sergei about some of my self-doubts, about how I was unsure whether I was too rude to Leonovich for criticizing

him for not training us hard enough, Sergei made me very happy by saying he liked me just the way I was.

My heart leaped when he said it, because to me, Sergei was always so much more mature than me, more solid than me, more knowledgeable

and sensible. He knew how to get joy from life, how to talk to friends, how to talk to coaches. He knew what he wanted in

life. I loved to watch him with his friends, how comfortable he made them feel, how comfortable he was around them. I was

even jealous of his friends, because I doubted I could make him feel as happy as they did. I was particularly jealous of Marina,

because she could keep Sergei’s attention and have long conversations with him. I thought that she had more talent than me,

more education, more musical knowledge. With me, Marina only wanted to discuss work and the programs, but with Sergei she

talked about other things. It’s probably why I became so focused on skating. I assumed they—Marina especially—thought

that I was the last person who knew about anything other than skating.

That’s why I was so happy when Sergei started to prefer to spend time with me, and talked to me like a friend. Like one of

his good friends. When I said something rude to Leonovich in practice, or acted moody, Sergei used to just make a face and

say something like, “It’s not a good idea what you’re doing right now.” He never raised his voice. If I kicked the boards

with my skate, which he hated, he never yelled. He’d say, “Don’t put yourself down. You’re not a little kid. If you’re disappointed

in yourself, don’t show it to people. You have to have enough strength to handle it.”

I don’t know where Sergei got his equanimity from, because his mother was not this way at all. Probably his father had this

same mentality. It’s why all of Sergei’s friends were proud to know him. He was capable of being as wild and crazy as anyone,

but when he needed to be strong, he was strong. I saw in Sergei what I was missing in myself, what I was looking for in myself:

confidence, stability, maturity. It’s why I idolized him so much, why I considered him beyond me and unattainable. He was

just a man for my dreams.

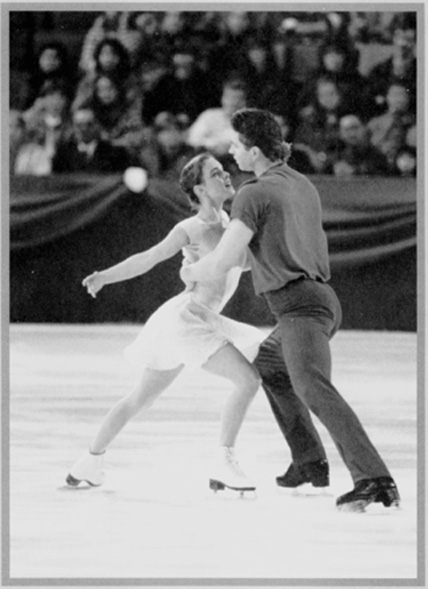

Stephan Potopnyk

I

didn’t eat properly in the fall of 1988. I suppose I was

trying to lose some of the weight I’d put on as my body was maturing. My guess is I wasn’t getting enough calcium in my diet,

but whatever the reason, I suffered a stress fracture in my right foot, which was diagnosed in November.

My father had driven me to the hospital, and he wouldn’t talk to me the whole way home. I was crying, very upset. My foot

was already in a cast, and I remember thinking that I shouldn’t have said anything about it, that I should have just kept

skating with the pain, which was endurable. That’s the way my father made me feel. The cast would stay on for a month, then

it would be another four weeks before I could get on the ice. It put the entire season in jeopardy, but this time off the

ice ended up being a very important period of my life. If I had been healthy, I wonder if things would have turned out as

they did.

I began studying English two days a week with a tutor. I had forgotten everything I’d learned in school, and even had to memorize

the letters again. But this was the international language, and I knew it was something I had to do. With my injury, I now

had the time. My mother had two grammar books she had saved from when she’d studied English in school, and they helped me

a great deal. I had also made a friend in California, a man named Terry Foley, who had sent me a pair of gold earrings after

we won the gold medal. He was an engineer with McDonnell Douglas, and during the summer he had come and visited us in Moscow

with his three daughters. I wrote him letters a couple of times a month in English, and he would send back my letters with

corrections. This, too, helped me to learn.

Sergei either visited or called me every day. Sometimes he came over to dinner, and once I made him a cake. I began to think

of myself as someone special in his eyes. My cast came off in mid-December, but the foot was still too painful and weak for

skating. Marina told me that ballet exercises were good for rehabilitation, and I went to Navagorsk to work with her on them.

I also lifted weights, swam, and practiced lifts with Sergei. He, of course, was also skating and used to run through the

new program Marina had created for us by himself.

I went down to the rink to watch him one day in late December. It made my heart ache to have to stand on the side while Sergei

skated through our program without me, and silly as it sounds, I worried every day that he might suddenly decide he was not

going to wait for me to get healthy and would choose a new partner.

“You look so sad, Katuuh,” he said to me, skating over. “So, you’d like to skate?”

“Of course I’m sad. Serioque, you’re jumping so well, and when I finally get on skates, I won’t be able to jump even two inches

off the ice.”

He smiled his wonderful, warming smile. “Come on. I’ll give you a little ride.” And with that he lifted me in his arms and

skated me all through our program. It was like flying, and my heart was beating so loudly I was sure he could hear it. It

was better than being well.

We invited Sergei to join us again for New Year’s, which we were spending this year up at the Volga River home of Yegor Guba.

Sergei said he didn’t know whether he would come or not. I bought him a bottle of grapefruit liqueur for Christmas. I was

so shy, and I thought I’d get him a good bottle of liqueur. It was called Paradise, and came in a green bottle with birds

on the label. I found out later this was really the kind of gift you’d give a girl, since it was a sweet liqueur with only

17 percent alcohol. But I didn’t know. I was just excited to do it.

On the morning of the thirty-first, my parents drove to Navagorsk to get me, but Sergei said he was going to celebrate New

Year’s with Alexander Fadeev instead. So I was quite upset. I wouldn’t show him my tears, though, and I gave him my little

gift and kissed him on the cheek. I could tell he was happy I did it.

We arrived at Yegor’s in the middle of the afternoon, and, still upset, I went up to one of the bedrooms to take a nap. In

the meantime Sergei and Sasha had changed their minds. The problem was, they didn’t have a car to get to Yegor’s, so they

had to flag someone down and pay him. On the way they drank the entire bottle of Paradise liqueur.

Sergei came up to my room to wake me. I was so surprised and happy to see him. I think he was a little drunk, because when

I asked him about the drive, he said, “Your liqueur was just perfect.” Then he asked if I would come with them to see Sasha’s

property. Fadeev had bought some land nearby, and he’d built a sauna on it. Only a sauna.

I assumed Sergei didn’t really want to take a sauna, since Yegor also had one, but was going there to get me away from my

parents. The three of us drove to Sasha’s land, and Sasha heated up the sauna. In Russia, saunas are usually small log houses

that have three rooms. The first room is for taking off the clothes. The next room has benches and a table, because in Russia

you must eat and drink, then sauna, then eat and drink some more. The third room has the sauna, which is heated by a wood-burning

stove.

Only Sasha took a sauna that day. Sergei and I sat out at the table and talked, and he gave me a small glass of vodka. He

said, “I want to tell you something.” But whatever it was, he was having trouble saying it. Even the vodka didn’t help. I

could see he wasn’t comfortable, but I knew there was something special on his mind.

Then he said, “Why don’t we kiss?” Something like that. It wasn’t really a question. He could probably see I wanted it, too.

He gave me a gentle kiss on the mouth, and when he saw that I liked it, he gave me another one that was longer. This one was

interrupted by Sasha coming out of the sauna to get something to eat. I was so embarrassed I couldn’t even look at him.

Sasha must have said something. I don’t remember, except I can picture him grabbing something off the table then disappearing

back into the sauna by himself. Sergei was smiling. I was probably blushing. Then when Sasha was settled back in the sauna,

we kissed a couple times more. This went on for quite a while. Sasha, poor guy, kept staggering out of the sauna to drink

vodka and breathe the cool air, embarrassed to interrupt us, but fearful if he didn’t he would die of the heat in the sauna.

Sergei and I would pretend to be happy to see him, making small talk and biding our time until he plunged back in. Finally

at nine o’clock at night Sasha said we’d better get back, since my parents would be wondering where I’d gone. I think he’d

lost about ten pounds.

I remember walking back and listening to the cold crunching of the snow beneath our footsteps. The fields were all blanketed

in white, and the moon gave us shadows. It was so beautiful, and I was so happy. I wondered, Why me? Why am I so lucky? I

was so young and small and shy, and Sergei could have had any nice long-legged girl. Why should he choose me? This is what

was going on in my head. I felt much older all of a sudden.