My Sergei (4 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

If a young army club skater failed to show sufficient improvement during the year, he or she was not promoted to the next

grade in the sports school. To give you some idea of how difficult it was, when I first started skating there were about forty

kids in my class who skated at CSKA. By the time I graduated, just five boys and five girls remained.

The club always had a year-end competition that was like a final examination. My jumps were not strong, which is why I could

never have successfully competed as a singles skater. The highest I ever finished in these competitions was third; the lowest

was probably sixth. When I was nine, my father came to one of these competitions, which was held at seven in the morning.

I was very nervous because my father was there, and when I was putting on my costume, I somehow zipped my hair in my dress.

I started to skate, but I couldn’t move my head. My ponytail was stuck in the zipper, lashing my head in place. Finally I

stopped the program and went to the judge, and he let me unzip my hair and start over. Afterward my father had a very long

face and big frown, and he didn’t come to any of my competitions again until I was skating pairs.

My father’s dream was still for me to become a ballet dancer, so when I was ten years old he asked me to try out at the central

ballet school in Moscow. I did it only because he wanted me to. That’s how obedient I was. However, I cannot truthfully say

I tried my best. I went with a friend, Oksana Koval, who was also a skater and was a head taller than me. She passed, and

I did not, because I was too short. Oksana is now a ballerina, but if she had not passed this test, it might have been she

who skated with Sergei. Such is destiny.

My father was very disappointed in me when I failed the test, very upset, but my mother was a little relieved. She knew how

hard it was to be a good ballerina, and how easy it would have been to fail after being selected. As for me, I wasn’t at all

concerned, because one of my skating coaches had told me, “Don’t worry about this exam. You’re going to be a great pairs skater.”

He had a talk with my father, too, and assured him that they would find a nice partner for me, and that I had a good future

in skating. Still, my father wasn’t happy. I was never quite good enough to please him. Maybe in the Olympic Games I was okay.

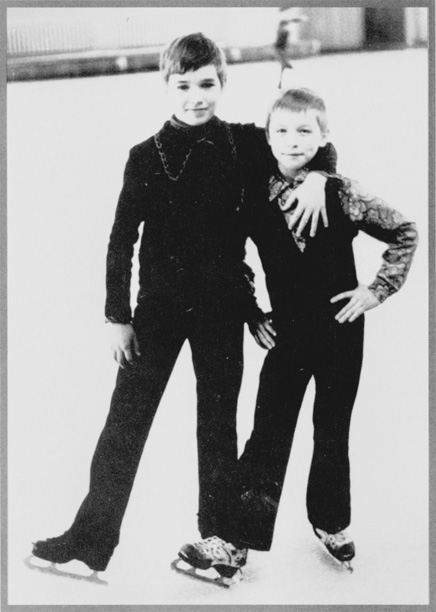

Sergei

(right)

was very tiny when he started to skate.

T

he spring I turned eleven, my friend Oksana Koval and

I were invited to skate on the large ice rink where the pairs and older boys practiced. Sergei was in this group. The coaches

had told us to come and skate, it’s no big deal, but my friend and I knew it was more than that and were proud that we were

the only two selected. As we circled the ice, we gathered from the conversations of the other skaters that it was Sergei for

whom they were seeking a partner.

That summer Oksana Koval joined the ballet school, and when I returned to the ice the next season, the pairs coach, Vladimir

Zaharov, told me to come early to practice. He had chosen a partner for me. I was very excited because I knew it was going

to be Sergei.

I had never spoken to him. I remembered seeing him on the ice with the older boys, and also in school, and he was slender

and narrow and handsome. But Sergei was so much older than me—four years, which at that age seems like a lifetime—that

I’d never thought it possible that we’d someday be paired together. At school Sergei had caught my eye because he sometimes

didn’t wear the mandatory blue uniform like the other boys. He wasn’t sloppy, though. He might wear a nice pair of slacks,

a jacket, and maybe a skinny black leather tie that was in fashion then. He didn’t carry a shoulder bag for his books like

everyone else but preferred to carry a briefcase. It was very stylish and made him stand out from the rest.

He was a good singles skater—he’d been skating at the army club since he was five years old—but he wasn’t a very strong

jumper, which is why they asked him to try pairs. There was some question as to whether he had enough upper-body strength.

Zaharov wasn’t sure. Sergei’s arms were tiny when we first started, so it helped that I was small. But once he began lifting

weights, he quickly matured. I have some pictures of him in the place where we trained in the summer, called Isikool, and

he was so beautiful. His upper body had already developed. But I was blind in those days and didn’t notice. I only thought

of him as a coworker.

He was always very quiet and shy, and didn’t like to tell stories about himself. Last summer, a few months before he died,

I said to him, “Serioque? I must be getting older. You know how old people are always thinking about their childhood? I’m

thinking more and more about my childhood.”

He told me, “Don’t worry, Katuuh. Me too. Let me tell you a couple of stories about myself.” Katuuh was the name he called

me in casual conversation. Katia he only used when he was serious: “

Katia,

we have to do the taxes today.” And when he wanted to call me his lovely, romantic wife, then he called me Katoosha, very

soft.

He had seldom talked about his childhood before. Of course I knew that both his parents—Anna Filipovna and Mikhail Kondrateyevich

Grinkov—worked as policemen in Moscow. It may seem strange that the son of policemen with no artistic background would become

a figure skater, but in the 1970s figure skating was very popular in Moscow. It was a young and growing sport, new to most

people but shown so frequently on television that a lot of kids wanted to try. And parents definitely encouraged their kids

to get involved in sports—any sports.

The Grinkovs were originally from the city of Lipetsk, which is eight hours away by train. So Sergei had no grandparents at

home to take care of him. Consequently his mother and father would bring him to day care when he was a young boy—six, seven,

eight years old—to a place where the children stayed all day and night. They’d drop him off on Monday and pick him up after

work on Friday. Sometimes his parents told him, “Don’t worry, Sergei, we’ll be back to pick you up early, maybe on Wednesday

or Thursday.” He’d wait and wait, his little face peering out the window at the street, and when they didn’t keep their word,

he’d cry.

The other story he told me was that in the winter his parents sent him to some sort of camp where the children took their

naps outdoors in hammocks—outdoors in winter. It must have been freezing. But the sun was so bright as it reflected off

the snow that Sergei and the other children had to shut their eyes against it. Then they quickly fell asleep. If you slept

well and didn’t cry, afterward you’d get a piece of chocolate.

After he told me these two stories, he observed that he’d come out of it all right, so we needn’t feel guilty about sending

Daria to American day care, where we picked her up each day at noon.

Anna, Sergei’s mother, has told me that she couldn’t keep Sergei’s clothes clean as a child. She’d change him for school,

warn him not to get dirty, and the next thing she knew, Sergei would have fallen into a tub of water. I can’t imagine that

she took such a thing in stride. He never complained about his mother, but Anna is quite a serious woman, severe even, as

one would expect of a Soviet policewoman. Nor was Sergei a model citizen at school. It wasn’t that he was particularly naughty,

or disrespectful, but Sergei hated conformity. And he despised hypocrisy even more. He didn’t see why he should smile at someone

he didn’t like. He never understood why I tried to be nice to people, to everyone, even if they had done something to hurt

me. We were very different in this way.

Sergei on a camping trip as a young boy.

He lived on the very border of Moscow, in an apartment beside the Moscow River. It was the last street before it became another

town, and you could actually swim in the river there. It was clean, and there was a little beach. Sergei liked the sea and

swimming, which he always preferred to hiking. He liked to play all sports—tennis, soccer, hockey—and like most boys,

he liked to play with toy soldiers. Anna told me he could sit in the bath for two hours with these soldiers.

Mikhail Kondrateyevich Grinkov, Sergei’s father.

I only met his father two times before his death in 1990, but Mikhail Kondrateyevich was very quiet, like Sergei, and also

big and calm. It was from his father that Sergei got his character. Sergei’s father was almost too huge to fit into his car,

and the first thing Sergei did when he had money was to buy his father a bigger automobile.

Their apartment had two bedrooms, a living room, and a small kitchen. Sergei’s sister, Natalia, lived there as well. She was

seven years older than Sergei and resembled him greatly—same eyes, same mouth, same shyness. He felt closer to Natalia than

anyone else. With both parents working, Natalia was like a surrogate mother to Sergei, and they looked to each other for company.

Natalia could always handle pain, which, to Sergei, was the most important trait a person could have. To not show your pain.

He was a stoic. He told me once that when he was five or six years old, he slammed Natalia’s finger in the door by accident.

They were playing some game, and she was chasing him. She grabbed her finger and ran into the bathroom to try to stop the

bleeding, shutting the door behind her so Sergei wouldn’t see the blood. She didn’t want to scare him. It was quite a severe

cut—she still has a nasty scar—but she never cried, and she never showed it to him until it had healed. He was still amazed

at this years later, that she could be so strong. She’s needed to be. Natalia’s had a difficult life.

Like so many young Russians, she was married briefly and had a daughter, Svetlana, but the marriage ended in divorce. Divorce

was very common in Russia in the 1980s, and one of the reasons for this was the lack of apartments. It wasn’t possible to

just buy an apartment. You had to go to the government officials, tell them you were married and living with your parents,

that your husband was also living with his parents, and that you needed an apartment. Then you had to wait until the government

gave you one. They put you on a list, but no one knew how long it would take. In the meantime, you had no privacy, you were

living with either one set of parents or the other, and there was a lot of stress that usually led to divorce. That’s what

happened to Natalia.

• • •

Zaharov was a great coach for beginning pairs skaters. He had been a pairs skater himself, from Sverdlovsk, which was the

home of many very good pairs skaters. He knew the best way to do all the elements, the easiest way. We have a saying in Russia:

It’s stupid to reinvent the bicycle. I think that’s one of the problems that pairs skaters have in the United States and Canada:

they try to learn all the elements their own way, as if it’s the first time it’s ever been done.

Zaharov was basically a calm man, nice and quiet, who was patient when he explained things at first. Only later did he begin

to lose his patience. He had olive-colored skin that became very tan in the summer, and also had blue, blue eyes. Zaharov

was about forty years old, not very tall, but was strong and tough. I especially remember his powerful hands. He was so professional,

and he could easily lift me off the ice to show Sergei the correct way to do the lifts. Sergei was just a teenager, and it

wasn’t at all easy for him. Zaharov used to make him practice all the lifts with a heavy chair made of iron, because a chair

is quite awkward to hold, and so is a person.