My Sergei (6 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

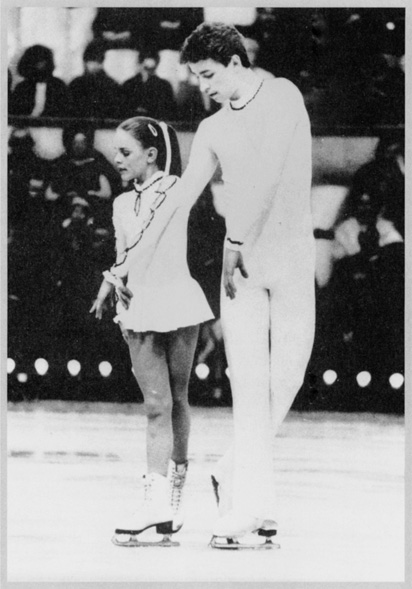

Another early program choreographed by Marina.

After the competition there was a banquet, and what I remember best was Sergei staying around the girl ice dancers, all of

whom wore beautiful dresses. He didn’t pay much attention to me off the ice. We were not very close friends yet and I was

very young, both in years and in experience. For example, on the plane ride home, I sat with Vladimir Petrenko, who was Viktor’s

younger brother and my age exactly. We ate ice cream, and this was unbelievable to us, beyond the realm of possibility, how

they could keep ice cream frozen for so many hours on the plane.

Sergei turned eighteen on February 4, and, for the first time, I gave him a gift. It was a key chain that my father had brought

back from Spain. It had a little gun on it that could shoot caps, and although this was a small gift, I was so shy that I

worried about it endlessly. But Sergei liked it and kept it with him, which made me happy.

That spring we competed in a Friendship Cup at a beautiful mountain resort in Bulgaria. After the competition our team went

outside together, and we were playing in the snow, having fun, throwing snowballs. Sergei loved that kind of horseplay. It

was then that, for the first time, I remember becoming aware that I found him attractive, and that it was nice to be with

him.

I never told anyone these feelings. To my great regret, I never had any close girlfriends to confide in. Maybe if I had been

spending more time at home, I’d have talked about my feelings with my mom. But we were so often at training camps or competitions

that I spent more time with Sergei than I did with my family. Among the other skaters in our club, Anna Kondrashova was the

girl I spent the most time with, but she was seven years older than me. To Anna, I was a child. Most of my life was like this.

I was seldom around kids my own age.

I had to try to figure out all these mysterious feelings on my own, which I was not equipped to do. I knew that I felt sad

sometimes, but I always thought I was sad because I was homesick. Not because I was lonely. I was so disciplined about training

when I was thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen that I never went to a friend’s house just to talk and gossip and do stupid

teenage things. That’s the age that girls discuss boyfriends and crushes and feelings. It’s a void in my life I’ll never be

able to fill.

And that’s one of the reasons I was so attracted to Sergei. He always had friends around him. He could go wherever he wanted

and do whatever he wanted to do. His life seemed very different from mine.

I

n May 1985 I turned fourteen. Sergei was too shy to come

to my birthday party, but he called me on the phone to ask if we could meet. We settled on a spot near the subway, a short

distance from my house. I was obviously excited. As I mentioned, Sergei seldom spent time with me off the ice. When he arrived

at the meeting place, he had with him a huge toy dog, white and light brown in color. It was quite expensive. Looking back

now, remembering how seldom Sergei ever surprised me with gifts, I’m amazed he had the courage to buy me this wonderful present.

Afterward, this dog was always in my bed.

Marina Zueva had created a difficult short program for us for the 1985–86 season, which was done to music by Scott Joplin

and involved lots of footwork and pantomime with our faces. Sergei had a nice, understated way of acting, using very natural

expressions that never distracted from our skating. Marina used to have me watch Sergei and try to do what he did. They thought

alike. She was closer to Sergei than to me, because he was older, and also because he shared her interest in reading. In her

eyes, I was always the little girl, too small for some of their philosophical conversations.

Marina also made a difficult long program for us to a medley of music by Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. The music was

much more sophisticated than what other pairs were skating to, and we liked it very much. But the choreography was hard. In

an early competition that year, Skate Canada, I fell as we did our side-by-side triple salchow, a challenging jump that Shevalovskaya

had added to our elements.

The head coach of the army club at that time was Stanislav Alexeyvich Zhuk, who by any definition was a miserable, pitiless

man. After my mistake, Zhuk told Marina that I had fallen down because it was a bad program. He would create a new program

for us, one that was plain and simple and showcased only elements, not choreography. He also said that he was coaching us

from now on, not Nadezheda Shevalovskaya. Thus began the longest year of skating that Sergei and I ever endured.

Zhuk, too, had been a pairs skater, finishing second three times in the European Championships from 1958 to 1960. He was in

his mid-fifties, short, with a big stomach and a round face. His most arresting feature was his eyes, which were small and

dark and looked very deep into you. They were very scary, peering at you from beneath his hairy eyebrows. All of Zhuk’s movements

were fast. He also had very strong but not very nice hands. I didn’t like it when he showed us movements with his hands. And

on the ice, when he demonstrated something to us with his feet, he couldn’t straighten his leg. It looked ridiculous.

Sergei used to laugh at Zhuk, but not to his face. We used to imitate the way he walked fast, taking very small steps. Sergei

didn’t like him as a person. Zhuk drank every night, and he used to speak harshly, even filthily, to the boys. He liked to

order them around as if they were soldiers, because they skated for the army club. “Shut up,” he would say, “I’m higher than

you in rank.” Zhuk liked these army rules.

We used to skate in the morning from 9:00 to 10:45, then afterward we’d spend forty more minutes practicing lifts. Then I

went to school, did my homework, and came back for the evening practice from 6:30 to 9:30.

Sergei and me with Alexeyvich Zhuk, 1985.

Sergei had finished high school, and during the day he liked to take a nap. But Zhuk believed you should not sleep for more

than forty-five minutes in the afternoon, or you would be too relaxed to train well that night. Our good friend Alexander

Fadeev, the singles skater who also trained with Zhuk, used to sleep for three hours in the afternoon. So did Sergei. As a

result Zhuk started telling people that Sergei was lazy and undisciplined. That he didn’t listen to the coach. That he missed

practices. He told me that I should change partners because of Sergei’s habits.

I hated him when he said that. I always believed Sergei was the only one who could skate with me. I never, ever thought I’d

change my partner. But Zhuk kept telling me bad things, and he had an expression he liked to use, accusing Sergei of “infringing

on the regimen.”

It made Zhuk furious that Sergei didn’t take him seriously, that he just ignored him off the ice. Sergei used to say to Zhuk,

“After practice, what I do is none of your business. If I want a beer, I’ll have one. If it’s Saturday and we don’t skate,

I won’t get up at 7:00

A.M.

”

Zhuk could have told me anything, and I would have done it. I was, if nothing else, obedient. So I worried that Sergei wasn’t

doing what he needed to be doing to become a champion. This was stupid of me, because in fact Sergei was lifting weights to

make himself stronger and was skating beautifully. No matter what he did—tennis, soccer, running—Sergei was always very

competitive with the other boys. He had his own code for living. Even though he never told anybody this code, he always lived

by it. Sergei knew what was right and what wasn’t. I knew only what I was told.

Zhuk’s goal seemed to be to keep us as busy as possible, and to keep us around him as much as possible. Maybe because he was

very lonely. Maybe because it was the only way he could keep himself from drinking. Zhuk wanted to control our lives. He used

to tell us, “If I don’t coach you, you’ll never be on the World or Olympic team.” He tried to make us completely dependent

on him, to make us think he was the only one who could look after our health and teach us how to eat and sleep.

He had us keep journals: how many jumps we attempted, how many we landed, how many throws, how many spins; how we felt before

practice, how we felt afterward. Every night we were supposed to update these things. Sergei wouldn’t do it. He’d take my

journal and copy it. But of course I kept mine scrupulously. I was so good about it. We had to bring our journals to practice

every day so Zhuk could see that we were doing them properly. And every month we’d have to add everything up—how many hours

altogether on the ice, how many jumps, how many landings, how many misses. Very, very scary.

In the summers Zhuk had two places he liked to take us for off-ice conditioning. One was to a resort on the Black Sea, with

a very mild climate, sort of like South Carolina or Virginia. We’d go there in mid-May and early June. We’d meet at 7:00

A.M.

every morning, and Zhuk would tell us what lay ahead for the day. Then we’d run from 7:15 till 8:45, always on a normal road,

never a special track, and never a special distance. Zhuk would just say run over there and run back. Do it twice, or whatever.

Sometimes we’d run along the beach, on the rocks and shells and sand, which was uncomfortable but probably good for strengthening

our ankles.

At 9:00

A.M.

we’d have breakfast, then we’d do exercises that were good for the arms. We’d go to a special place near the sea that had

big, round rocks, and we’d take these rocks and throw them forward, backward, and to the side. It was supposed to make our

jumps better. The rocks weighed about five pounds, and we’d throw them back and forth fifty, sixty, seventy times. Zhuk was

always very specific about how many repetitions. And of course I always did them exactly as he ordered. Then maybe we did

some pushups and situps.

The worst was running the stairs. Zhuk always took us to places that had stairs. The longest was 225 steps; another had 175

steps. Sometimes he made us not run, but jump up the stairs, first with one leg and then with the other. Always with a stopwatch,

and always we’d have to record what we’d done in the journals. Then at night, at our evening meeting, he could say “Today

you were better” or “Today you were worse; we’ll have to do something with you.”

Zhuk also thought that undersea diving was important for skaters. Snorkeling. He said it helped you control your breathing.

You learned to take a deep breath and to hold it. But in skating, you don’t have to control your breathing. Only Zhuk, this

madman, thought you did. I remember once in the middle of May he told everyone we were going spearfishing with him. It was

his favorite hobby. Naturally I was the only skater to show up, and I was so angry at the others for not telling me they weren’t

going to come. Just me and Zhuk. It wasn’t summer yet, and the sea was cold as ice. I was freezing. He told me to put some

clothes on over my swimsuit, so I would be warmer. So I did. The flippers were too big because they didn’t have a small enough

size for my feet, so I added a couple of pairs of socks. I put on a sweater, warm pants, and even a warm hat. I hate the sea

anyway, and since I don’t swim well, it was so scary. Then Zhuk went into the water with his speargun and made me follow behind

him.

In July, when the weather got hot and humid, Zhuk used to take us to Isikool, a health resort in the mountains. I preferred

this place to the Black Sea, even though the altitude made the training on the stairs very difficult and painful. There was

a beautiful, deep lake at Isikool about which there were lots of legends, and in the afternoons we used to go on long hikes

through the woods. We played soccer and tennis, and sometimes Sergei and I would play mixed doubles together. Although he

was always very competitive when he played with other boys, he was never competitive with me. I, however, used to get upset

when I made a mistake, and Sergei would laugh and shake his head and ask me what I was getting upset about. We were supposed

to be playing to have fun.