My Sergei (2 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

He wanted to someday move to Idaho. To Sun Valley. We’d skated there a few times and both liked it very much. Sergei liked

to ski. I loved the mountains. We loved the nature there, the forests, the beautiful night sky brilliant with stars. The wildlife

and the great open spaces. This was a place for a family to dream.

He wanted to drive me through Europe. Or perhaps he would have taken me on the best train. He wanted to stop in all the cities,

to visit the cathedrals and museums. He wanted to eat at the sidewalk cafes, to have wine with our lunches, and long naps

in the afternoon when we were tired. He wanted to walk the boulevards while holding hands, to have no schedule to keep, or

exhibitions to skate in, or competitions to train for, as we’d had for so much of our lives. No more rushing around without

seeing. We talked of this trip many times.

I’m going to keep this list and add to it as I think of other things. Sergei wanted to do so much, so many different things

besides skate.

A

s I look back, I see that everything went too smoothly

for me. I had no experience with the sadness of life. Even before I met Sergei, I was a happy child, innocent and naive,

blessed with good health and much love.

My father, Alexander Alexeyevich Gordeev, was a dancer for the famous Moiseev Dance Company, a folk dancing troupe that performed

throughout the world. He had strong legs and a long neck like a ballet dancer, and a stomach that was absolutely flat. Everything

he did, he did fast, and he always moved quickly around the house. I can remember my father jumping over swords when he danced,

bringing his legs up to his chin as the knifelike blades flashed beneath him, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen times in a row. Or

he’d kneel down and kick, left and right, left and right, in the athletic manner of the folk dancers of Russia.

My father wanted me to be a ballet dancer. That was his big dream. He was disappointed that I became a skater. He had gray-blue

eyes, the same color as mine, and a kind face. But he was also strict and serious, as if his kind face didn’t quite match

the words that came out of his mouth.

He met my mother, Elena Levovna, at a dance class when she was fourteen. They married when she was nineteen, and I was born

when she was twenty. My mother was the sweet one, always perfect with children, the person I most admire on this earth. Selfless,

generous, she was also quite beautiful as a young woman, five feet six inches tall, with a tiny waist and a very feminine

figure. She walked like a ballerina, one foot just in front of the other. Her hair was brown, like mine, and wavy. Her fingernails

were strong, and she polished them red and wore makeup every day. I used to watch in fascination as she applied it. She was

always tender with my younger sister, Maria, and me, smiling much more often than my father.

My mother and me.

She worked as a teletype operator for the Soviet news agency Tass. She was proud of her job, which paid her 250 roubles a

month—more than my father made—and she liked to look nice when she went to work. She always wore high heels and beautiful

clothes that my father had brought back from overseas, attire that set her apart from most Soviet women. She, too, traveled

for her work. When I was eleven, my mother spent six months in Yugoslavia, and the next year she worked twelve months in Bonn,

West Germany. Even when she was based in Moscow, my mom worked long and irregular hours, from eight in the morning till eight

in the evening one day; then from eight in the evening till eight in the morning the next.

With my father in 1974.

So my maternal grandmother, Lydia Fedoseeva, took care of me and my sister. We didn’t have to worry about day care or babysitters.

We called her Babushka, and she was an important person in my life. She was short and a little heavy, but walked very nimbly

and was full of energy.

One time, when I was twelve, we were training at a place on the Black Sea, and one of the other skaters left my suitcase in

the Moscow airport. The boys were in charge of the bags, the girls were in charge of the tennis racquets, and when I got off

the plane, I had this boy’s tennis racquet but he’d forgotten my bag. I could have killed him. So I called home to ask them

to send my suitcase to me.

My grandmother went to the airport and picked up my bag, but she didn’t trust putting it on an airplane by itself. So she

took it on an overnight train to Krasnodar, five hundred miles, then took a bus to the resort where we trained. I got a call

from the guard at the gate saying my bag had arrived. I went to pick it up, and there was my grandmother. I wanted to cry

when I saw her. “Babushka, what are you doing here?” I asked.

She told me she had brought me my suitcase. She only stayed a few hours, then she walked to the bus and took the overnight

train back home to Moscow.

Her hair was always short and neatly styled. When my grandmother was nineteen years old, her hair turned completely white,

like paper, and ever since, she went regularly to the hairdresser. Her face was darling; her voice soft and soothing. I loved

to listen to her read to my sister and me at night. My favorites were Grimm’s fairy tales. Very, very scary. My grandmother

did most of the cooking, and I liked to help her in the kitchen. She taught me how to knit and sew, and made my skating costumes

for me until I was eleven. She taught me how to suck the yolks out of eggs and decorate the shells for Easter. That was one

of my family’s favorite holidays. A few weeks before Easter came, Babushka used to take a plate, fill it with earth, then

plant grass in the earth. She watered it and tended it until the grass grew up. Then on Easter morning we’d hide painted eggs

in the grass for my sister, Maria, to find.

My grandfather—my mother’s father—also lived with us. His name was Lev Faloseev, and I called him Diaka, which is short

for

diadushka:

grandfather. He had been a colonel in a tank division during World War II, a prestigious position that enabled us to live

in a lifestyle that was, while not extravagant, quite comfortable by Soviet Union standards. He taught about tank warfare

at the Red Army academy in Moscow. He always wore a uniform to work, covered by a warm gray coat in winter, and a big fur

hat and strong leather boots. His uniform always smelled very weird to me, pungent and musty, so he took it off as soon as

he came home. Then he would have a nice long dinner, followed by a glass or two of cognac.

He called me Katrine—nobody else called me this—and he liked both me and my sister very much. He was a calm man, a quiet

man, who used to let Maria and me play with his medals from the war. We also liked to look at his books. I remember thumbing

through his history books and geography books, which were very old and filled with maps of famous battles, much more interesting

than our fairy tales.

We lived in a five-room apartment on the eleventh floor of a twelve-story building on Kalinina Prospekt, near the Russian

White House, where the parliament meets. It was a fantastic location, with a good view of the Moscow River. From the balcony

we used to be able to watch the soldiers on parade march past our building on their way to Red Square. It was also a beautiful

spot to watch holiday fireworks, which were aimed so they’d come down in the river. The Olympic torch in 1980 was also exchanged

on our street. I remember watching the ceremony from our balcony when I was nine years old.

From what I could tell, I was the luckiest girl on earth, wanting for nothing. Like most children, I never thought much about

the rest of the world. I never heard bad things about the United States, either on television or in school, was never frightened

that someone would drop bombs on us, and never worried that the United States and the Soviet Union would go to war. It was

more like: We’re the happiest country; we’re the greatest nation. I was fourteen before I began to learn anything about politics,

and by then I understood, or started to, that when the government tells you something, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s true.

• • •

My parents used to vacation for a month every summer at the Black Sea. I hated to swim. I’ve always hated to swim, I don’t

know why. I’m not very good at it, and my mother tells me that the only time I ever got angry as a child was when I couldn’t

do something well. But in a roundabout way, a Black Sea vacation was how I got started skating.

On one trip my parents met a skater who trained at the Central Red Army Club. The club was known by its initials: CSKA, an

acronym that we pronounced

cesska.

The army, like many trade unions in the former Soviet Union—automobile manufacturers, farm equipment makers, coal miners,

steel workers—sponsored sports clubs throughout the country, and the biggest and most prestigious of these was CSKA. These

sports clubs—and there were hundreds and hundreds of them nationwide—were quite professionally run, with the best coaches

and facilities. They turned out the elite athletes that made the Soviet Union an international powerhouse in sports.

One key to the success of the clubs was identifying talented children at a young age and teaching them sound fundamentals

so they could reach their full potential. Tryouts were held by age group, and they were open to anyone. Your parents didn’t

have to have any army affiliation to join CSKA. If your child was selected, the club was free of charge. It was affiliated

with a sports school in Moscow that also provided the young athletes with an education. It was a great honor to be admitted

to any sports club, but particularly CSKA, because sports was one of the few means by which a Soviet citizen could travel

and see the world; and top athletes also got many privileges unavailable to the ordinary citizen, like hard-to-find Moscow

apartments, cars, and relatively generous monthly stipends.

This skater knew of my father’s dance company, and he suggested that my parents bring me to the rink at the army club in September

to try out. I was only four years old, too young to start ballet and too young even to try out for skating. But this friend

lied to CSKA officials and told them I was five, which was the age at which you were allowed to join. I was very tiny, which

is an advantage for a girl in skating, and they took me right away.

It was impossible to find skates small enough to fit me in Moscow at that time, so I wore several pairs of socks beneath the

smallest skates my mother could find. The first year I skated twice a week, a regimen that increased to four times a week

when I was five. It was just an activity to me, something to give me exercise. I didn’t have any goals in mind. If it hadn’t

been skating, it would have been gymnastics or dance. My mom never really believed I’d be anything special as a skater until

Sergei and I won the Junior World Championships when I was thirteen. She just wanted me to be a normal kid and thought whatever

I was doing was great. I never dreamed about Olympic medals or traveling the world like my parents. On the ice, I was not

a good jumper. I just liked to skate.

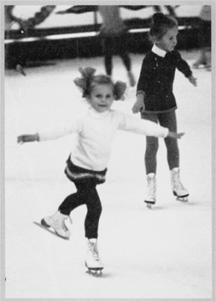

I started skating at age four.