My Sergei (10 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

It was the first time my family did this. My mother dropped the plate at the first stroke of midnight, and we all scrambled

to grab a piece and ran away. I don’t remember where I hid my piece, but I do remember what I wished. I wished I would skate

well in the Olympics. And I guess it came true.

That year the European Championships were held in Prague. I still wasn’t in very good condition. Since my fall, I’d lost some

weight and strength, and I was still having headaches. I wasn’t eating well, for whatever reason, and was nervous about everything.

Sergei and I didn’t skate our best, but we won anyway. I missed something—a jump or a throw, I don’t remember—and I was

so upset, as if I’d done something terrible. Sergei said, “Don’t worry about it. It’s not the Olympic Games yet. We’ll be

ready in time.”

But at that championship it became clearer than ever to me that Sergei felt more responsible for me on the ice. I liked it

very much. I’d always been a little nervous about whether he’d pay enough attention to training, but now that I wasn’t as

strong as I should have been, Sergei had become stronger, more secure, more serious. I felt that despite my weakness, Sergei

would take care of me. During the Europeans we ate breakfast, lunch, and dinner together. Then, after we had won, we danced

together at the banquet. It was a fast dance, but it was the first time I remember just the two of us dancing. Sergei never

really liked to dance.

Then we went to Navagorsk for the final preparations before Calgary. The whole Winter Olympic team was there, and the doctors

checked our blood pressure and weight every day. I was down to eighty-four pounds, having started the season weighing ninety.

I felt okay, but I was very stressed out and tired. I couldn’t relax or eat properly. I think because all season everyone

was so serious about the Olympics, because we kept being tested by the doctors, because the coaches kept telling us we had

to be in the best shape of our life, I just assumed I should lose weight. The Olympics, I believe, are a year-long celebration

of the nerves, and I was too young to understand what it was doing to my body.

I remember having lots of meetings at Navagorsk where team officials went through the schedule with us many times, and talked

about the spirit of the Olympic Games. They told us about Canada, how we had to be a team, to help each other, be more friendly

with each other, take care of our health—all this stuff. I don’t think anyone was listening. I didn’t like it, because they

were taking up time when we could have been resting.

Then we were given our Olympic uniforms. I got boots for the opening ceremonies, but they weren’t my size, so I saved them

for my mom. This happened to me all the time. The skirt and jacket they gave me to wear were huge, so huge that not even my

grandmother could tailor them to fit me. I looked terrible in them. I was always so jealous of the Canadian and American teams,

because they always had sizes that fit even the tiny girls. Meanwhile I was wearing these big ugly things that made me look

like a bag lady.

As the day of departure neared, everyone began giving me advice. They were all so worried about me because I was so young

and tiny. It was driving me crazy. “Did you ever read this book?” someone I barely knew would ask. “Maybe you should read

this book.” It got so crazy that after all the waiting, all the hard work and training, when the day finally came to leave

for the Olympic Games I didn’t want to go. I missed my mother so much. We’d been training in one facility after another, and

going from one competition to the next, and I felt almost like I’d been taken from my family against my will. It really surprised

me, but all I wanted was to stay home with my mom.

O

n January 27, 1988, we flew to Montreal, spent the night,

then took a morning flight to Calgary. Sergei held my hand the entire plane ride. It’s strange, but it didn’t mean anything

to me. It was just nice, and I was a little proud to have his hand on mine. But I was so focused on myself, so consumed with

the thought of the Olympics, that it didn’t say anything to me about his feelings. I should have been in heaven, but I was

quiet and withdrawn, thinking only of our training. Maybe that’s why everyone was so worried about me and always giving me

advice.

After picking up our credentials, we drove to the nearby town of Okotoks. It was more than two weeks before the opening ceremonies,

but our coaches wanted us there early to get accustomed to the time change. It was a quiet town, and we stayed at the Okotoks

Inn, a cute, small hotel. It was very cold, but there wasn’t a lot of snow.

Townspeople came to our practices every day, which presented some problems. It’s tough to have people clapping when you’re

trying to work on an element. Practice isn’t supposed to be a performance. You’re concentrating, then another skater makes

a jump and suddenly there’s a burst of applause. I found it very distracting. But the people were certainly nice, and the

first day one of the spectators gave me a doll.

Sergei’s twenty-first birthday was on February 4, and they presented him with an ice-cream cake after the morning practice.

Elena Valova gave him a card that showed a stork bringing something in a blanket, and when you opened the card you saw it

was a bottle of liquor. He could now legally drink. For luck, Sergei wore a gold chain around his neck with a horseshoe charm,

and I gave him a pendant with the Calgary Olympic symbol on it to wear on this chain. I was nervous about giving it to him,

and afterward everyone teased him: Whooo, Katia gave something to Sergei. But it made me happy when he wore it.

The ice dancers arrived in Okotoks a week after we had, and Tatiana Tarasova, who coached the team of Natalia Bestemianova

and Andrei Bukin and would one day coach Sergei and me, brought me some gifts from my parents: chocolates, a letter, and a

picture of them with my sister, Maria. And caviar. When athletes from the Soviet Union traveled, we always carried extra caviar,

and it was invaluable when bartering for Levi’s, music tapes, or cash. But in Calgary we didn’t have any caviar to trade,

because when the team officials gave it to us, they opened it. They wanted us to eat it for the protein.

We moved into the Olympic Village on February 8, which was beautiful and very well laid out. Each time we went in we had to

go through security, and they checked our bags carefully, which took a long time. It took forever if we were on a bus. Also,

all the women athletes had to go through sex control, to make sure we were really women. They took a little scraping from

the inside of your cheek, examined it in a lab, then gave you a card that said you had passed.

Sergei got a bad stomach flu and a fever the day we moved into the Village, and he became so ill that he couldn’t skate for

two days. The speed skating doctor put him in his own room to tend to him. It was scary for me. This doctor, whose name was

Viktor Anikanov, wouldn’t let Sergei eat anything for two days. Sergei was so pale that I was worried he wouldn’t be able

to compete. But by the third day he’d recovered and was fine.

About the only thing I was eating was cheesecake. The cheesecake they served in the athletes’ cafeteria was the best I’d ever

tasted, and every day that was my meal. I ate salad, too, and maybe yoghurts and fruit. But no meat. Nobody told me not to

eat meat, but I’d decided on my own that I was not going to eat it. In fact, everyone was telling me to eat this and this

and that too, worried that I was too thin, and it was driving me crazy.

Because the boys were living on a different floor from the girl skaters, I didn’t see Sergei as much as usual. I was rooming

with Anna Kondrashova. Once in a while I’d bump into Sergei around the Village, and he’d be with Sasha, who was his roommate,

or with some other friend. But I didn’t feel comfortable just coming up to their room and talking to them, or sitting with

them if they were already eating. Elena Valova and Oleg Vassiliev were nice to me, but because I was so small they would tease

me with remarks like “What are you eating?” or “Why don’t you eat anything?” I didn’t feel like listening to it. So I’d go

to meals by myself and eat whatever I wanted. I wrote in my journal that I missed home very much. There I was, about to compete

in the Olympics, and all I wanted was to go home. Can you imagine?

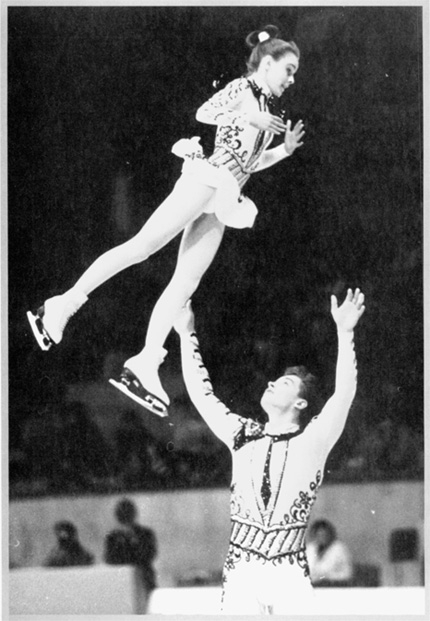

A difficult element from our short program.

The ice rinks in Calgary presented some problems. The Saddledome, where the competition was going to be held, was huge and

comfortable and had a regulation Olympicsize surface. But it was seldom available to us for practice, since so many hockey

games were being played there. So we practiced every day in a Canadian-size arena, which was shorter and narrower than we

were used to at home. Sergei and I had to be careful not to hit the boards all the time, and it was unsettling to go back

and forth between these different-size ice surfaces.

We had decided not to march in the opening ceremonies, since the short program was the following day, and we had a practice

that afternoon. Instead, we watched them on television. The next morning the head coach of CSKA, Viktor Ryshkin, visited to

wish us luck. We felt close to him, and it was great for my morale to see him. He also brought me hugs and kisses from my

parents, plus candies and still more caviar and another letter from my mom. Reading it brought me lots of energy. I now remembered

who I had to skate for: my parents, who had given me so much. I also wrote in my journal that today was my first Valentine’s

Day, which in North America, I’d been told, was when lovers exchanged gifts. But it wasn’t a holiday for Russians, so Sergei

and I didn’t exchange anything.

I was confident. I can’t explain why. All the waiting was finally over, and I think the anticipation had been what was making

me crazy. The short program, the toreador march, went almost perfectly, and we were scored first. The only problem, a small

one, was when we finished we had our backs to the judges. We looked up and—oops—no judges. We’d lost our bearings during

our final spin. But we just laughed a little bit and turned around to make our first bow, and no one knew about this mistake

except us.

I’d already decided how I was going to celebrate when it was over. There was a special soda fountain in the game room of the

athletes’ village, where you could have ice cream dishes made up any way you wanted: toppings and whipped cream, a hundred

flavors to choose from. I promised myself I would go there every day when the pairs skating was over. I was always like this.

I wasn’t able to spoil myself until after a competition. Anna Kondrashova had no such qualms, and every day I jealously watched

her eat one of these fabulous sundaes. She let me try a little bite, and it was every bit as good as it looked.

Before the free program, I remember looking at Leonovich, and he was so pale and wan it made me smile. I said to him, “Stanislav

Viktorovich, please try to look happy. It can’t be as bad as you’re making it look with your face.” Leonovich always used

to get quieter and quieter and quieter before we skated. He never had any last words for us. Even if he’d tried to say something,

we never would have heard it, because he’d speak so softly. All the strength went out of him before we competed. The funniest

things sometimes popped into my head at such times, and this time I was thinking, Poor Stas, why must he be so nervous for

us? He could be home with his wife and kids, completely relaxed and enjoying the skating on television.

We skated the long program as well as we’d ever done it, and by a unanimous vote of the judges, we won the gold medal. Afterward

I was proud, but not ecstatic. We didn’t organize any special celebration, at least not one in which I was included. Leonovich

didn’t take me anywhere. Elena and Oleg, who won the silver medal, went out with Sergei, leaving me behind. I was left to

enjoy my ice cream by myself, but as it turned out, even that fell through. After waiting all those days, when I went to the

game room to create a fabulous sundae, I found they had closed the soda fountain for good. I was so angry that I went to the

regular cafeteria and took three bowls of ice cream, but it wasn’t the same.