Nabokov in America (16 page)

Read Nabokov in America Online

Authors: Robert Roper

and the prosperity

13

of the numerous Cokers [founders of Coker College], who seem to own half of Hartsville, is founded on this very cotton industry. It is picking time now, and the “darkies” (an expression that jars me, reminding me … of the “Zhidok” [“Yid”]

of western Russian landowners) pick in the fields, getting a dollar for a hundred “bushels”—I am reporting these interesting facts because they stuck mechanically in my ears.

He is not a Northern liberal shocked to see that things are different in South Carolina, but he goes far, for him, in the direction of recognizing a social evil and showing concern. “My lecture about Pushkin … was greeted with almost comical enthusiasm,” he tells Véra, after informing his Spelman audience that Pushkin had had an African grandfather. He is pandering, a little, but pandering with a wholesome truth.

These letters later figured in plans for a sequel to

Speak, Memory

, a book he hoped to write someday about his American experience. He would call that book

Speak On, Memory

(or maybe

More Evidence

, or maybe

Speak, America

)—it was to have been about his friendship with Bunny Wilson and his years of exploring the West, with his college lecture tour from the first year of the war as foundation. The bundled letters followed him to Switzerland when he resettled there in the sixties, but the book never quite took form. Rereading his letters was for the older Nabokov intensely moving. “

I need not tell you

14

what agony it was,” he wrote Edmund Wilson’s widow in 1974, two years after Wilson’s death, “rereading the exchanges belonging to the early radiant era of our correspondence.” He had waited too long to harvest the book, as sometimes happens, even with writers of “genius.”

In May ’43, Nabokov told Laughlin that he had finally finished

Nikolai Gogol

, a book that “has

cost me more trouble

15

than any other I have composed… . I never would have accepted your suggestion to do it had I known how many gallons of brain-blood it would absorb.” It had been hard to write because “I had first to create” the writer (that is, translate him) “and then discuss him… . The recurrent jerk of switching from one rhythm of work to the other has quite exhausted me… . I am very weak, smiling a weak smile, as I lie in my private maternity ward, and expect roses.”

Laughlin was puzzled by the manuscript. He had wanted a sturdy introduction, to bring Gogol to the attention of readers who might have barely heard of him, and Nabokov had written an eccentric gloss in the manner of William Carlos Williams’s

In the American Grain

or D. H. Lawrence’s

Studies in Classic American Literature

. Those works had first appeared in the twenties. Lawrence was another European

exile, someone who had struggled to find himself in America, and his study, like Nabokov’s, is furiously concerned with the flavor of authorial voice. Hoping to salvage some “classic” American writers—Franklin, Cooper, Crèvecoeur, Poe, Hawthorne, Melville, Dana, Whitman—from their reputation as authors of “children’s books,” Lawrence argues for their irreducible “

art-speech

16

.” The “old American art-speech contains an alien quality,” he says,

which belongs

17

to the American continent and to nowhere else… . There is a new voice in the old American classics. The world has declined to hear it, and has babbled about children’s stories… . The world fears a new experience more than it fears anything… . The world is a great dodger, and the Americans the greatest.

Lawrence’s book cost him

18

much trouble, as did Nabokov’s. It grew out of a similar hope: to find in America an audience to replace an audience in Europe with which he felt increasingly out of step. He roughs up his classic Americans in much the way Nabokov does Gogol.

*

Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that Nabokov had read Lawrence’s book. Lawrence was one of the authors he never mentioned without an ostentatious sneer; he had read some Lawrence, he admitted (the novels probably), and Lawrence’s daring way with sex and the immense notoriety of

Lady Chatterley’s Lover

, the most banned book of the twentieth century, were Lawrentian developments so relevant to Nabokov’s future career that his sneer, when he affected it, might have signaled a debt of an uncomfortable size.

In the first chapter of

Studies

Lawrence says,

There is a new feeling

19

in the old American books, far more than there is in the modern American books, which are pretty empty of any feeling… . Art-speech is the only truth. An artist is usually a … liar, but his art, if it be art, will tell you the truth of his day… . The old American artists were hopeless liars. But they were artists… . And you can please yourself, when you read

The Scarlet Letter

, whether you accept what that sugary, blue-eyed little darling of a Hawthorne has to say for himself, false as all darlings are, or whether you read the impeccable truth of his art-speech… .

Like Dostoevsky posing as a sort of Jesus, but most truthfully revealing himself all the while as a little horror.

Lawrence seems to be winking at the future Nabokov here, Dostoevsky being the Russian writer whom Nabokov most scorned.

Style is what makes meaning

20

for Lawrence; primitive America makes itself known, becomes real, only in the voices of homegrown artists, whom, however, Lawrence does not exalt as geniuses, whom he regards with a mixture of love and condescension.

March of ’43, Nabokov learned he had

gotten his Guggenheim

21

: $2,500. Wellesley invited him back to teach again, and the MCZ renewed his research position at $1,200 a year. Immediately he began planning another trip west. On the California trip, he had had fun in New Mexico, collecting “

near a place which

22

had some connection with Lawrence,” he told Wilson (probably somewhere in Taos County). “You were

going to tell me

23

about a place you knew, when something interrupted us… . What we want is a modest, but good boarding-house, in hilly surroundings.”

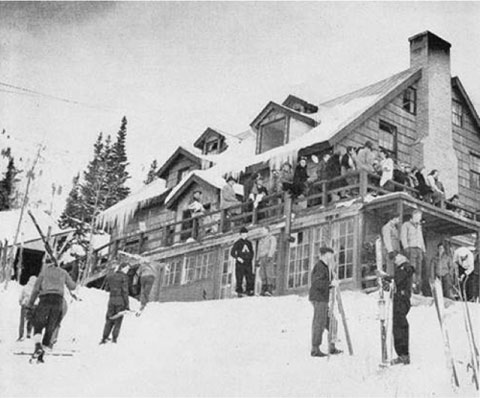

Mountains were important, because mountain terrain favored the evolution of new species. Laughlin, who had not yet read the Gogol book, invited the Nabokovs to stay at a ski lodge he co-owned near the village of Sandy, Utah, southeast of Salt Lake City. The place was at an elevation of 8,600 feet, in a long,

tumbling canyon

24

full of aspens and granite, under high peaks that reach to 11,000 feet. Utah had been only lightly harvested by lepidopterists. The family traveled west by train.

This was the summer during which Dmitri helped his father bag specimens of

Lycaeides melissa annetta

. In a letter at the end of the war to his sister Elena, who was riding out the war in Prague, Nabokov sketched Dmitri’s character. He noted “

a propensity for pensiveness and dawdling… . He does extremely well at school, but that is thanks to Véra who goes over every bit of homework with him.” Dmitri had “an exceptionally gifted nature” but, again, “a dose of indolence,” and he could “forget everything in the world” to submerge himself in an “aviation magazine—airplanes, to him, are what butterflies are to me

25

.”

†

His son was “

vain, quick-tempered

26

, pugnacious, and flaunts American

expressions” that were “pretty crude,” although, by the standard of American schoolboys, he was “infinitely gentle and generally very lovable.”

Aged eleven, Dmitri was still being sent to school in that “gray suit with a red jockey cap.”

The waywardness

27

that Nabokov emphasized would be a theme years later, in scolding, loving, anxious letters that Véra wrote her son when he was a student at Harvard and then in Italy, where he was starting an operatic career. While granting Dmitri great freedom, which he used to cultivate excitements of many kinds, the Nabokovs were also shaping him for a kind of work that in the long run would confer honor on him and sustain him morally and financially, in part. They made him a worker in the family cottage industry, whose product was books signed “Nabokov.” His Russian, which was his because his parents had made sure to speak it with him, was expressive but “appalling” as a written language; in his first year in college, Vladimir wrote Roman Jakobson, the renowned Harvard structuralist linguist, saying that the boy was “very

anxious to take a course

28

with you” and badly needed work on his grammar. This was a step, though by no means the first step, in a long campaign to equip him to translate his father’s work.

Alta,

Laughlin’s lodge, now an iconic American powder-skiing destination, was a kind of mountain fastness. The family took the train to Salt Lake and then caught a ride into the mountains, but then they were more or less stranded, since no one among them drove, and they had no car anyway. Véra was uncomfortable in the weather. She would come to marvel at mountain thunderstorms and hailstorms, but Alta was windy and cold that summer. Relations with Laughlin and his wife were also edgy, verging on chilly. Laughlin had promised “moderate” terms for a room, but in Laughlin the “

landlord and the poet

29

are fiercely competing,” Nabokov wrote Wilson, “with the first winning by a neck.” Like other scions of great fortunes, the publisher was eager not to be taken for a mark, and he drove hard bargains with many of his writers. His argument with Nabokov about the Gogol book was real and inflected what happened over the summer. He wanted plot summaries of Gogol’s works, among other additions that Nabokov found laughable. Vladimir grudgingly supplied a chronology and a new final chapter, “Commentaries,” which holds the publisher up to ridicule, but which Laughlin had the good form to publish as Nabokov wrote it.

The tone of the chapter—recalling the famous sketch by Hemingway, “One Reader Writes”—reports Laughlin saying such things as “ ‘

Well … I like it—but I do think the student ought … to be told more about Gogol’s books… . He would want to know what those books are

about

.’ ” Vladimir replies that he

said

what they are about, to which Laughlin answers, “ ‘No… . I have gone through it carefully and so has my wife, and we have not found the plots… . The student ought to be able to find his way, otherwise he would be puzzled and would not bother to read further

30

.’ ”

In Hemingway’s sketch, published in

Winner Take Nothing

(1933), a woman whose husband has contracted syphilis writes to an advice columnist asking for basic information about the disease. Her prudery invites ridicule and seems intended as an indictment of American women, or maybe just of American wives. Nabokov’s sketch is almost entirely dialogue: usually he disdained writing that was heavily dialogue-based, Hemingway’s most definitely included in the derogation, but here he uses naturalistic speech to clever effect, showing the thickness of the character identified as “the publisher” with every word out of his mouth. The “I” of the dialogue is patient and sane by contrast and justified in feeling exasperated; he is the victim of someone enamored of his own ideas who also, unfortunately, signs the checks. A technique often said to be an invention of Hemingway’s, leaving out

passages for a reader to infer, has a near-parodic demonstration in the sixteenth paragraph, when, after the patient author is asked to recite the plot events of

The Inspector General

, and gives a laughably literal summary, the publisher says, “Yes, of course you may use it,” in reply to an unvoiced request to put it in the revised manuscript.

Nabokov had an

especially keen disregard

31

for Hemingway.

Faulkner he dismissed

32

with similarly appalled commentary, but Hemingway bestrode the era of Nabokov’s arrival in America as a colossus, his fame and sales evoking in many writers a troubled response. In the year of Nabokov’s arrival, 1940, Hemingway was dominatingly present, with the publication in October of

For Whom the Bell Tolls

, his long, sporadically excellent, crowd-pleasing novel of the Spanish Civil War. Nabokov admitted to having read Hemingway. In an interview in the sixties he said, “

As to Hemingway

33

, I read him for the first time in the early forties, something about bells, balls, and bulls, and loathed it. Later I read his admirable ‘The Killers’ and the wonderful fish story.” “Bells, balls, and bulls” conflates

For Whom the Bell Tolls

with

The Sun Also Rises

, and “the wonderful fish story” is probably

The Old Man and the Sea

, another crowd-pleaser but definitely minor Hemingway. “The Killers” is an early dialogue-based story, virtually a screenplay. It has

influenced American film

34

but gives a decidedly narrow idea of Hemingway’s resources as a writer.