Napoleon in Egypt (15 page)

VI

The March on Cairo

N

APOLEON

planned to begin his march on Cairo as soon as possible. Desaix’s division, which had secured the beachhead at Marabout and had not taken part in the assault on Alexandria, had afterwards advanced and camped on the outskirts of the city.

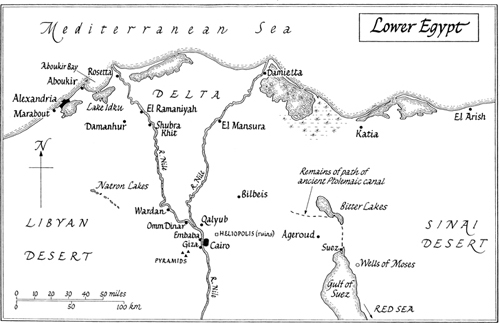

As early as the evening of July 3, just a day after the fall of Alexandria, Desaix was ordered to set out for Damanhur, forty miles to the southeast, the first stage of the 150-mile march to Cairo. Before he left, Napoleon advised him: “If attacked, screen your cavalry, show the enemy only your infantry platoons. Do not use light artillery. It is necessary to save this for the great day when we shall have to fight four or five thousand enemy horse.”

1

At this stage, such advice was superfluous. The unloading of the fleet was still under way in the port, and Desaix was forced to leave with no artillery, and minimal cavalry support. Even this small contingent was in no fit state to embark upon a long march across the desert, let alone take part in a battle; the horses had not yet recovered from their long sea journey, and according to Desaix, in a vain appeal to Napoleon, “we have only two days’ supply of oats for the horses, and no other fodder.”

2

The men each had just four days’ supply of dry biscuits, and their individual canteens of water.

Initially, the route followed the dried-up bed of the canal linking Alexandria to the Nile. Despite the state of the canal, Desaix’s Bedouin guide assured him that there would be sufficient wells at the villages on the way, and that Damanhur itself was a highly civilized city four times larger than Alexandria.

Two days later, Reynier’s division marched from Alexandria along the same route, to be followed by two more divisions on the subsequent days. Meanwhile a fifth division under General Dugua left for Rosetta, some thirty miles along the coast to the east, at the entrance to the western navigational channel of the Nile. In parallel with Dugua’s division, a flotilla under Captain Perrée set off for Rosetta by sea. This consisted of over a dozen gunboats and ships with a draft of less than five feet, with a complement of 600 sailors. Once Rosetta was taken, Desaix’s division was to march south and rendezvous with the other four divisions at El Ramaniyah. Perrée’s flotilla, augmented by captured river boats from the port at Rosetta, would transport bulk supplies of rice, lentils and other provisions down the Nile to victual all the divisions converging on El Ramaniyah.

On July 5 Napoleon held a meeting in Alexandria with thirteen local Bedouin chieftains, organized for him by El-Koraïm. These were the very men who had harassed Napoleon during his advance on Alexandria, but he succeeded in persuading them that he came as a supporter of Islam, and as such was their true friend. He assured them that the sole purpose of his presence in Egypt was to rid the country of the Mamelukes, and that once he had done this he would return to the Bedouin the land from which they had been dispossessed by the Mamelukes. The Bedouin chieftains agreed to sell Napoleon 300 good horses for use as cavalry, and 500 riding camels, as well as allowing him to hire a further 1,000 pack camels along with their minders for transport duties. They also supplied him with spies, who would travel ahead of his army during its march on Cairo, seeking out information about the Mamelukes’ military movements.

For a payment of 100 piastres, the Bedouin also agreed to release the thirteen French prisoners they had taken during the advance on Alexandria. According to Bourrienne, these were duly returned and brought before Napoleon, who sought to obtain from them intelligence about life amongst “these semi-savages.”

3

He asked one of the returned prisoners, “How did they treat you?” whereupon the man dissolved into tears.

“Why are you crying?” demanded Napoleon.

Between sobs, the man explained that they had been subjected to what Bourrienne tactfully describes as “the treatment so well known in the Orient.”

“You big booby,” remonstrated Napoleon. “That’s not too bad. Serves you right for falling behind the column. You should thank heaven for having come out of it so lightly. Now stop blubbing and answer my question.” But as Bourrienne drily observed, “the little time that he had spent amongst the Arabs, and the way they had treated him, had prevented him from making the least observation, and he was unable to tell his commander anything at all.”

News of what had happened to these prisoners quickly spread through the ranks, leaving them with no illusions about the consequences if they were captured and their lives spared. Although this was more than half a century before the Geneva Convention (of 1863), in Europe historic practice had established various rules of war concerning the treatment of prisoners; these were on occasion violated, by mistreatment or even slaughter, but the French soldiers were unprepared for this particular violation.

In the event, the return of these prisoners was to be the only part of the agreement the Bedouin fulfilled. When the chieftains returned to their tribes they received word from Cairo that the grand mufti (the chief expert in Muslim law) had decided that the French should be placed under a

fetfa

, or

fatwa,

a decree declaring that all true Muslims should take up arms against them. In one fell swoop, Napoleon had not only lost his promised transport, but the wilderness through which his army was marching had been transformed once more into hostile territory.

Among the first to become aware of this were the columns of Dugua’s division, who were forced to fend off Bedouin attacks as they made their way up the coast, then along the narrow sand spit separating the brackish Lake Idku from the sea. Only when they were halfway along the spit did they discover that their maps had not taken into account a recent change in the ever-shifting geography in and around the Nile delta. The small channel linking the lake to the sea had become wider and deeper. Dugua now found himself trapped, with the Bedouin waiting behind him at the entrance to the spit, while his entire division could muster less than half a dozen vessels, each capable of transporting only fifteen men at a time across the water. Fortunately Dugua managed to signal to Captain Perrée, whose flotilla was keeping up with them, just off the coast, and the flat landing craft came inshore and assisted in carrying the men across the channel. In an attempt to speed up this painfully slow operation, the horses and requisitioned pack camels laden with equipment were coaxed into swimming alongside the craft; despite this, the entire operation lasted from first light until well into the night. The forty-mile march to Rosetta, which should have taken less than three days, ended up taking almost twice as long, with Dugua’s division not sighting the minarets of the city until the morning of July 8.

But time was made up when they reached Rosetta, which offered no resistance. At the approach of the French the hated Mameluke governor Selim Bey had called upon the local population to slam closed the gates and take to the walls in defense of their city. But already several copies of Napoleon’s declaration to the people of Egypt had reached Rosetta, and the population was in no mood to respond to Selim Bey’s call to arms. Quickly sensing the situation, he and his attendant Mamelukes had fled the city.

In contrast to the dusty ruins of Alexandria, the French soldiers found Rosetta “surrounded by gardens filled with palms and orchards containing dates, lemons, oranges, figs, apricots and all manner of other fruit.”

4

The town itself had well-built modern houses belonging to European merchants along the quayside bordering the Nile. The inhabitants stood at the doorways of their houses watching as the columns of French troops marched past, some of the locals even coming out to offer bread, fruit and water to the soldiers. Soon the plentiful market reopened and the soldiers were able to replenish their rations of dry biscuit with fresh fruit (at only slightly exaggerated prices). According to the journal kept by Dugua’s chief of staff, Colonel Laugier, Rosetta “was the first pleasant impression we have experienced since our arrival in Egypt.”

5

The troops were similarly impressed.

In line with Napoleon’s orders to all his commanders to “make friends and respect the mosques,” Dugua quickly summoned the local dignitaries, making plain to them his peaceful intentions and his respect for Islam. He assured them that all promissory notes issued by the French army in payment for provisions would be honored by the paymaster-general in Alexandria. As a result he was able to start purchasing in bulk the rice and lentils to be transported by Perrée’s flotilla down the Nile. But this pleasant interlude would not last long. Just over twenty-four hours after Dugua’s arrival, he received a messenger from Napoleon, who had assumed that Dugua had already arrived at his rendezvous thirty miles down the Nile at El Ramaniyah. It looked as if Dugua was now in danger of holding up the entire advance on Cairo; there was nothing for it but to secure Rosetta and set off up the Nile at once.

As per instructions, Dugua proceeded to garrison Rosetta, leaving behind Menou, who was still recovering from the wounds he had received in the taking of Alexandria, as military governor of the city. Shortly after midnight on July 10, his division began the march south, with Perrée’s flotilla following them up the Nile. As dawn broke, the marching French columns were greeted by the timeless sight of the lush Nile delta. Colonel Laugier recorded, “We followed the main channel of the Nile, passing through cultivated fields criss-crossed by irrigation ditches filled with water. The local peasants stood beside the road to welcome us and watch us pass. They seemed prosperous enough and had a proud almost majestic air. Their women were joyful and greeted us with soft cries which uncannily resembled the cooing of doves.”

6

The soldiers gathered watermelons to supplement their rations, with their officers understrict orders that these should be paid for. On July 11 the advance columns of Dugua’s division began arriving at El Ramaniyah, where they linked up with the divisions led by Desaix and Reynier, and the two following divisions, which had marched overland from Alexandria. By contrast with Dugua’s men, these four divisions were in a pitiful state.

Desaix’s men had departed from Alexandria during the night of July 3-4. As night faded and the sun rose over the vast arid wilderness, the soldiers began to experience the debilitating heat and privations of the Egyptian desert, conditions for which they were particularly ill-prepared. In the interests of secrecy at the embarkation ports, the men had been issued with no equipment suitable for the desert. Their woolen uniforms, intended for campaigning in Europe, soon proved all but unbearable as the heat rose to 35ºC (95ºF) and beyond. Their individual water canteens were quickly emptied, and there were no water wagons to replenish them. The men soon began to suffer from extremes of thirst and the debilitating effects of dehydration, and as if this was not enough, the increasingly bedraggled columns trudging across the sand now faced the

khamsin

, or “poisoned wind.” According to Lieutenant Thurman, “in the midst of a fine morning the atmosphere became darkened by a reddish haze, consisting of infinitely many tiny particles of burning dust. Soon we could barely see the disc of the sun. The unbearable wind dried our tongues, burned our eyelids, and induced an insatiable thirst. All sweating ceased, breathing became difficult, arms and legs became leaden with fatigue, and it was all but impossible even to speak.”

7

Since time immemorial the fierce hot

khamsin

from the hinterland desert had been the curse of Egypt, its dust and grit finding its way into everything—penetrating the eyes and the nostrils, getting into bread and all food, to such an extent that teeth were ground down during eating. This is particularly noticeable in the ancient Egyptian mummies, whose teeth were sanded so smooth that some of the first archaeologists speculated that they belonged to an earlier evolutionary stage in our dental development.

In time the leading columns of Desaix’s division began to come across a number of remote villages. These typically consisted of “makeshift dwellings just four feet high with walls made of earth or sometimes mud bricks baked in the sun. They differed in size according to the size of the families which lived in them. You could only enter them bent low, and inside you couldn’t stand upright.”

8

When Desaix’s columns came to the first villages, the soldiers broke ranks and besieged the wells, quickly drinking them dry. At word of the advancing French army, the villagers had fled, taking their livestock with them. The villages themselves were eerily deserted, with no sign of food, which meant there was no opportunity to supplement the soldiers’ meager rations of dried biscuits, many of which had become worm-eaten during the long sea voyage. As the men pressed on, they found that the village wells had been filled with stones and refuse, which the sappers labored to clear. According to the savant Denon, “at the bottom of these wells they would find just a little brackish muddy water, which they would scrape up with cups and distribute amongst the men in small measures like shots of brandy.”

9

By now there was no mistaking the fact that they were traveling through territory that was more than just geographically hostile, and once again lines of mounted Bedouin began harassing the flanks, threatening to carry off any stragglers.