Napoleon in Egypt (20 page)

Murad Bey’s fellow ruler Ibrahim Bey was in many ways his opposite. Where Murad Bey was passionate and extravagant, Ibrahim Bey was more cautious and devious. Although he was capable of dismissing one pasha after another, almost at whim, whenever they displeased him, and dispatching them back to Constantinople, he also made sure that the annual tribute, the

miry

, was sent to Constantinople without fail. Where Murad Bey acted on impulse, Ibrahim Bey was a calculating realist. On occasion, he would attempt to restrain his fellow ruler from his worst excesses, but only when these resulted in indignant delegations of merchants or beys descending upon Cairo, or a further flight of

fellahin

to Syria. Even so, his interventions had little effect. Between the two of them they were ruining a country which had already sunk into a sorry state of neglect. The chaotic rule of the Mamelukes seriously hampered trade, as even the European traders found it difficult to meet the whimsical tariffs demanded by the beys. And beyond the cultivated regions of the Nile valley and the delta, the wilderness territory had fallen to the Bedouin tribes, who had to be bribed to ensure safe passage.

The Mameluke “taxes”—in effect little more than demands for money with menaces—had reduced the

fellahin

to penury. The Mamelukes claimed possession of the land, only allowing the

fellahin

to rent out plots, and extracting a tithe at every harvest. In recent years there had been several “bad Niles,” when the annual flooding had been insufficient to water more than the fields nearest to the irrigation channels of the Nile valley and the delta, and the

fellahin

were more wretched than ever. The harvest was gathered in May, and from then on the land lay uncultivated, becoming increasingly parched by the unrelenting sun until the Nile flooded once more in August, covering much of the delta in water, leaving a similar sight to that observed by Herodotus over twenty centuries previously.

Under Mameluke rule there was no provision for improving the irrigation canals and saving water, or even for basic maintenance of the water systems upon which all agriculture depended. As a result, the

fellahin

lived much as they had done in Herodotus’ time; indeed, much as they had done during the time of the pharaohs well over three millennia previously, when things had in fact been much better organized. The crops remained the same as they had been since time immemorial: a rotation of wheat, barley, beans and lentils, with rice as a staple and flax for mats and building materials. The lack of social stability, which had lasted through much of the five centuries of Mameluke rule, meant that there was no possibility of progress. The country that had once built the pyramids had yet to see the introduction of the wheelbarrow. Its most technically complex method of raising water from one level to another, a process upon which its very survival depended, remained the Archimedes Screw.

*

The administration of the country, such as it was, remained incorrigibly corrupt and unsystematic. The law rested on the judgment of the kadis, who turned to the Koran for their authority; outside the teachings of the Koran there was no legal code as such. Life for the impoverished downtrodden

fellahin

was a long, hard daily toil, with only the occasional grim and dangerous distraction, as their Mameluke masters fought amongst themselves. The historian Christopher Herold admirably evokes the scene:

The peasants, glancing up from their labours, would observe [the Mamelukes’] gleaming cavalcades, all aglitter with steel and resplendent in multi-coloured turbans and flowing silken gowns, galloping toward their equally glittering foes, skirmishing for a while, then either entering the capital victoriously or tearing south at a lightning gallop toward Upper Egypt, where they would lie low until there arose an opportunity to fight another day.

9

The historic stasis of the countryside also extended into the towns and cities it enveloped. Cairo’s era of greatness had reached its pinnacle during the early fourteenth century, when it had a population of almost half a million, making it larger than any city in Europe or the Middle East. And this greatness extended to far more than just its size: culturally no city outside China could match it. Profiting from the influx of Islamic scholars fleeing the Moguls during the previous century, along with the decline of Baghdad and Damascus, Cairo’s Al-Azhar mosque and university had become the major center of religious teaching throughout the Islamic world, a region that extended from Morocco to the Philippines. This wealth of learning extended into mathematics and the sciences, as well as medicine, knowledge of which subjects far exceeded that in medieval Europe. Such intellectual wealth was supported by the more tangible wealth of the spice trade between the Far East and Europe, whose sea route passed up the Red Sea, then overland to the Mediterranean. Almost all of Cairo’s great religious, and to a lesser extent secular, architecture dated from this period.

However, after the initial stability brought about by Mameluke rule, there were increasing periods of decline, caused by a nexus of calamitous circumstances: the devastation wreaked by the Black Death in 1348, the consequent inability of the rulers to control the Mamelukes, and the collapse of the spice-trade sea route monopoly after Vasco da Gama pioneered the route around Africa to India in 1497. The Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517 merely confirmed Cairo’s status as a provincial backwater, and the two ensuing centuries witnessed the city’s decline into cultural aridity—maintained by chaotic rule, fundamentalist religious teaching appropriate to a seventh-century desert society, and a majority population of illiterate and dispirited peasantry.

Revolutionary France saw itself as the liberator of mankind. Its army had defeated kings and princes in Europe, and even the pope, in the name of freedom. Age-old ruling dynasties quailed at the approach of its idealistically inspired soldiers. Even during the reign of the Directory this remained much how the French army liked to see itself, and Napoleon too subscribed to this fading myth, though very much for his own purposes. The French had come to Egypt to liberate the downtrodden Egyptians from their Mameluke tyrants, to bring to a backward people the benefits of European civilization and culture. Who could resist the chance of such enlightenment? As such, the French expected that they would be welcomed, once the initial suspicions of the people had been overcome. Their oppressive Mameluke masters would soon be put to flight.

But the reality was to hold some unexpected surprises. When news first reached Cairo that the French invasion fleet had arrived off Alexandria, “the beys and their henchmen let out cries of joy; Cairo was lit up in celebration. ‘It will be like slicing open watermelons,’ they cried. ‘Every Mameluke will vow to bring back a hundred heads.’” Or so the story goes. These words appear in Napoleon’s memoirs, and seem to be confirmed by very similar words in the memoirs of several French officers.

10

Nicolas Turc paints a somewhat different picture: “When Murad Bey learned [of the invasion] he threw the letter to the ground and called for his soldiers with a roar. His eyes became red and fire devoured his entrails. He ordered his horse to be brought and arrived at the residence of Ibrahim Bey in a passionate state. Soon news of the infidel invasion spread through the city, where it caused strife and confusion, the inhabitants pouring out of their houses filled with consternation and anxiety.”

11

Ibrahim Bey and Murad Bey called a

divan

, a council of state that was attended by the pasha Abu Bakr, as well as the senior beys, sheiks and

ulema

. Murad Bey immediately confronted the pasha: “The French could only have arrived here with the consent of the Porte, and being their representative here you must have known of this. Destiny will aid us in our struggle against you and against them.”

The pasha rejected this accusation, adding: “Be courageous and steadfast, rise up like the brave men you are, prepare to fight and resist with force, before placing your fate in the hands of God.” Some of the beys and

ulema

insisted: “We must exterminate the Christians in our midst before marching against the infidels.” Already the mob had begun to desecrate Christian churches and was threatening houses in the European quarter, crying out, “Cursed infidels, your last hour has arrived. We are now allowed to kill you and ransack your houses.” But the word of Ibrahim Bey and Pasha Abu Bakr prevailed. Ibrahim Bey ordered that the European quarter be sealed off, and its inhabitants were escorted to the Citadel for their own safety, while at the same time a collective fine of 20,000 francs was imposed on them for good measure. Later they were given shelter in the palace of Ibrahim Bey’s wife, a woman renowned for her piety and charity, who saw no anomaly in offering hospitality to the compatriots of the very people her husband might soon be fighting against.

The duplicitous letter that Napoleon sent to Pasha Abu Bakr from Alexandria, claiming that the Porte had “withdrawn its protection from the beys,” and inviting the pasha to come and meet him, evidently did not reach its intended recipient. The pasha summoned Bardeuf, the leader of the French community in Cairo, for an explanation of the French invasion, but he too said that he knew nothing about it, though significantly he did suggest that the French army might perhaps be on its way to India. Meanwhile Murad Bey assembled a force of around 6,000 Mamelukes, 15,000 armed Egyptians and 3,000 Bedouin, and set forth from Cairo, heading north. According to El-Djabarti, “As soon as Murad Bey left Cairo a mood of sadness and fear descended on the city. . . . At sunset the crowd deserted the streets. Seeing this state of affairs, Ibrahim Bey ordered the cafés to stay open during the night and ordered the inhabitants to light lanterns in front of their houses and shops.”

12

This perhaps accounts for the reports which reached Napoleon of the city being lit up in rejoicing at the prospect of defeating the French. El-Djabarti also records how, “after the departure of Murad Bey from Cairo the

ulema

gathered every day at the El-Azhar mosque and read the Holy Books for the success of the Egyptians; the sheiks of the main sects also assembled in their mosques and called upon God, while the holy scholars did the same in their schools.”

13

By the time Murad Bey and his forces returned after the indecisive encounter at Shubra Khit, Ibrahim Bey had assembled a force on the eastern bank of the Nile at Boulac outside the gates of Cairo. Again, estimates vary as to its strength, but it seems he certainly had at least 1,000 Mameluke cavalry, along with their attendants. (Each Mameluke took into battle as many as three or four attendants; during a charge the riders would fire their pistols and then simply toss them over their shoulders to be gathered up by their attendants, who would also, occasionally, be used as infantry support.) Ibrahim Bey’s force also included a number of artillery pieces, as well as several thousand separate infantry. Perhaps as many as half of these would have been trained militia; the rest would have been conscripts,

fellahin

and the urban poor, most of whom would only have been armed with sticks and the like. These in turn were accompanied by a throng of women, children and spectators, amongst whom were musicians playing tambourines and flutes, as well as others chanting—all of whom had come along to watch the battle against the infidels. Sources indicate that this gave something of a holiday atmosphere to the proceedings, though others mention that this procession also chanted fervent prayers for victory. Judging from the previous consternation on the streets of Cairo, many in this procession would certainly have been frightened and fearful of what might happen to them if the infidels from faraway Europe prevailed.

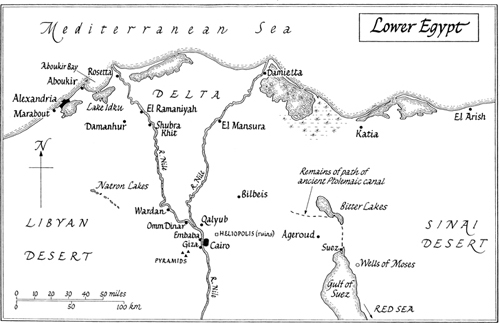

Meanwhile Murad Bey and his forces took up their positions across the Nile at the village of Embaba. Nikola and his boats were ordered to blockade the Nile, then dig in and mount artillery around the village itself. When Napoleon was informed that the Mameluke forces were split in two, he could hardly believe his luck. This tactical blunder was probably due to the headstrong Murad Bey. Had he crossed the river and joined forces with Ibrahim Bey outside the city walls, not only would this have consolidated the Mameluke fighting strength, it would also have forced Napoleon to make a river crossing if he was to take Cairo. Such an operation would have left him highly vulnerable, especially from cavalry attack and the artillery of Nikola’s flotilla.

By the evening of July 20, Napoleon’s five divisions were assembled at Omm-Dinar, at the head of the Nile delta, where they were allowed but a few hours’ rest. At one in the morning the drums began sounding through the darkness, wakening the men and beating the call to arms; an hour later the men were ready to depart on the final leg of their march on Cairo. One by one the divisions moved away into the darkness in battle formation. Just over two hours later, as first light broke over the eastern horizon, the French soldiers were greeted by a spectacular sight, the like of which not even the hardiest of well-traveled veterans had seen before. To the left of them, across the Nile, they could see the myriad domes and mosques of Cairo rising against the pink dawn. Dominating this skyline were the castellated walls of the Citadel, which dated from the time of the great warrior Saladin, the scourge of the Crusaders, who had retaken Jerusalem in 1187. According to Napoleon, his soldiers greeted their first sight of Cairo with “a thousand cries of joy”:

14

they had at last arrived at their destination. As the sun rose above the low Moqattam hills to the east, its rays passed over the expanse of the flat plain to the west of the Nile, and the soldiers could see in the distance the triangular mounds of the Pyramids, their stone flanks turning golden in the sunlight. Gradually, as they marched towards the three pyramids, their solid stone forms began to shimmer and melt in the heat haze, and across the floor of the plain could be distinguished a long arc, which glinted like jewels in the sunlight, stretching between the banks of the Nile and the pyramids, a distance of some eight miles. This, the soldiers soon realized, was the line of Murad Bey’s Mameluke cavalry with its attendants and accompanying infantry.