Napoleon in Egypt (56 page)

The Siege of Acre

T

HE

historic port of Acre (modern Akko) was first mentioned in an ancient Egyptian document dating from the nineteenth century

BC

; its natural harbor, overlooked by a fortified hill, made it one of the best-defended locations in all the Levant. Originally a Phoenician city, it was taken by Alexander the Great in 336

BC

early on his march to India, and in the twelfth century

AD

it became the capital city of the Crusaders, who named it St. Jean d’Acre (the name still used by the French at the time of Napoleon’s invasion).

Ahmed Pasha el-Djezzar, to give him his full title, had been governor of Acre and the surrounding

pashalik

(pasha’s domain, or province) for almost twenty-five years, during which time he had reinforced the ancient walls to the point where they appeared all but impregnable. Djezzar was now an old man, judged to be somewhere in his late sixties or early seventies, but he still lived up to his title of “Butcher.” He had been born with the name Ahmed, growing up in a remote mountain region of Bosnia at the western edge of the Ottoman Empire. During his youth he became involved in a murder, fled Bosnia and joined the Ottoman navy. But he proved unsuited to naval life, and deserted his ship after a quarrel, ending up on the streets of Constantinople, where he was soon penniless and starving. In order to survive, he took the drastic step of selling himself into slavery, and was shipped to Egypt to become a Mameluke, where he was taken into the service of the ruler Ali Bey. (His youthful service may well have coincided with that of the equally fearsome Murad Bey, who would later marry Ali Bey’s wife Setty-Nefissa.) Ali Bey was still struggling to establish himself, and the young Bosnian played a leading role in the elimination of his rivals. His behavior towards those enemies unwise enough to fall into his hands alive soon led to him earning the nickname Djezzar (“The Butcher”), which was proudly incorporated into his name.

After the death of Ali Bey in 1773, Djezzar had fled from the powerful Mamelukes (among them Murad Bey and Ibrahim Bey) who fought to take over Egypt, eventually being taken into the service of the Bedouin sheik Dahr al-Omar, emir of Syria, who appointed him governor of Beirut. Djezzar repaid this generosity by overthrowing and murdering him. In characteristic fashion he then wreaked his vengeance on those who had supported Dahr al-Omar, notably the local Jewish, Druze and Greek Orthodox populations

*

—often cutting off their noses, ears or feet, gouging out their eyes, or having their feet shod with horseshoes. It was around this time, in 1777, that Baron de Tott visited the region, but as he recorded in his journal, “I did not choose to have any connection with [Djezzar],” citing as his reasons “the cruelties for which he was infamous, and the oppression which made him dreaded.”

1

Even so, de Tott still saw chilling evidence of Djezzar’s handiwork: “He had walled in alive a number of Greek Orthodox Christians, when he rebuilt the walls of Beirut to defend it from the invasion of the Russians. One could still see the heads of these unfortunate victims, which the Butcher had left exposed, in order the better to enjoy their torments.”

Djezzar remained a loyal servant of the Ottoman Empire, promptly paying his

miry

in full to the sultan, an unusual generosity not displayed by all distant governors of this far-flung empire. Yet in reality he was virtually independent, and despite his growing years remained an energetic and fearsome character. According to an intrepid English visitor who was bold enough to accept his offer of hospitality:

Djezzar was at the same time his own chief minister, chancellor, treasurer and secretary, often even his own cook and gardener. . . . In his antechambers one encountered his servants, who were mutilated in all kinds of ways; one had lost an ear, another an arm, another an eye. We English were announced into his presence by a Jew, formerly his secretary, who had paid for an indiscretion with the loss of an ear and an eye. After a pilgrimage to Mecca [Djezzar] had killed with his own hands seven women from his harem whom he suspected of infidelity. He was sixty years old; but his vigour was still that of a man in the prime of life. We found him seated on a mat in a room without furnishings; he was wearing the clothes of a simple Arab and his white beard fell down over his chest; tucked into his waistband was a dagger encrusted with diamonds . . . we had a long conversation with him, during which he cut all sorts of shapes in paper with some scissors; this was how he occupied himself all the time when foreigners were introduced to him. He presented to Captain Culverhouse a cannon which he had made out of paper, saying to him: “This is the symbol of your profession.” All his conversation was in allegories, symbols and images.

2

Djezzar had seemingly always had a particular hatred for the French, and when Napoleon invaded Egypt this blossomed into a fanatical obsession: he would crush the infidels who had the temerity to launch another crusade into the lands of Islam. But when Napoleon started his full-scale invasion of Syria, Djezzar was soon intimidated. His raging and threats against Napoleon had included a degree of bluff, and he watched warily as Napoleon advanced in apparently unstoppable fashion up the coast towards him. After losing Gaza, Djezzar had quickly withdrawn his troops from Haifa, and had been on the point of withdrawing from Acre when two more remarkable characters arrived on the scene, both of whom had previously had dealings with Napoleon.

One of the British ships arriving off Acre had put ashore a French engineer by the name of Louis-Edmond Phélippeaux, and it was he who had persuaded Djezzar to stay and resist the French, advising him on the best tactics to adopt against Napoleon, and how to build up the defenses of Acre. This was the very same Phélippeaux who had shared a desk with Napoleon at military school in Paris, topping the class and subjecting his neighbor to frequent kicks. When the Revolution broke out, the young Count Phélippeaux had gone into exile, later serving as a lieutenant-general under the Prince de Condé when he landed in the Vendée in 1793 at the time of the Royalist uprising. Sometime later he had been taken prisoner, but had managed to escape on the very night before he was due to be guillotined. His accomplices in this escape had been a male ballet dancer and the descendant of an English earl, and in 1797 the three of them returned clandestinely to Paris with the aim of rescuing prisoners of the Revolution. Eventually they hatched a plot to free three Englishmen from the Temple, the notorious prison where Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette had been held prior to their execution. After a series of adventures worthy of the Scarlet Pimpernel, the plot succeeded. One of the English escapees was the maverick naval captain Sir Sidney Smith, who consequently managed to get Phélippeaux commissioned into the British army as a colonel. He then took Phélippeaux on board when he was put in charge of the English battleship

Tigre

, which ended up off Acre when Napoleon arrived in March 1799.

3

The life of Sir Sidney Smith was as remarkable as that of Djezzar and Phélippeaux. He too had had previous dealings with Napoleon, at the siege of Toulon in 1793 when the young Captain Bonaparte’s artillery fire had forced the British to withdraw from the city. In the course of this withdrawal, Sir Sidney Smith had remained ashore until the last minutes, detonating the arsenal and setting fire to the remaining ships in an attempt to prevent them falling into French hands—one of many such acts of reckless bravery which he would display during his extraordinary naval career.

Sidney Smith had been born in 1764 in London, the son of a rakish naval captain and a disinherited heiress. He had joined the navy at the age of thirteen, soon experiencing a hurricane, a mutiny, and action in the Atlantic against the French. Distinguishing himself under fire, he rose to the rank of captain at the extraordinary age of nineteen. When peace was signed with France, he embarked upon a prolonged tour of the French ports and became friends with several of the naval officers against whom he had previously fought. Acting on his own initiative, he also became a spy for the British Admiralty, whilst at the same time conducting a number of love affairs (“I let the heart go as it will”).

4

In 1790 he set off for Sweden, sailing up the Baltic in a seven-foot longboat with only a Portuguese cabin boy as crew, making a spectacular entry into the Swedish naval base at Karlskrona. King Gustav III was so impressed by the dashing young Englishman that he appointed him as his chief naval adviser, a post Smith gratefully accepted despite having been expressly forbidden to do so by the British Admiralty. During the Swedish war against the Russians, he showed extreme bravery under fire, on one occasion saving the king’s life and preventing him from being captured, for which he was knighted by the grateful Gustav before he returned to England.

In 1792 Sir Sidney Smith, now dismissively nicknamed “the Swedish knight,” was dispatched on a spying mission to Constantinople, where his brother was in charge of the British Embassy. Despite his undercover mission he cut such a conspicuous figure at court that he gained the friendship of Sultan Selim III, and then joined the Turkish navy as a volunteer. On hearing that Britain and France had declared war, he bought a small lateen-rig at Smyrna, which he renamed

Swallow

, and sailed across the Mediterranean to join Hood at the siege of Toulon, where he was to thwart Captain Bonaparte and earn the enmity of the French for his rearguard action. With some justification, the French regarded Smith as a pirate, owing to the fact that when he turned up at Toulon he was acting in a freelance capacity, and had not been recommissioned by the British navy. On his return to Britain, he was duly commissioned, given command of a ship, and led a series of flamboyant raids against enemy shipping along the French coast. During one of these raids he was captured, taken to Paris to face a charge of piracy, and incarcerated in the Temple prison. It was from here that he was rescued by Phélippeaux.

Back in Britain, Smith was appointed to command the

Tigre

, an eighty-gun battleship which had been captured from the French. He was given orders to join the British fleet in the Mediterranean, and given the diplomatic title “minister plenipotentiary,” authorizing him to deal with the Ottoman sultan on Britain’s behalf. He sailed forthwith for Constantinople, taking along his new friend Phélippeaux. Surprisingly, considering that Smith was officially a deserter from the Turkish navy, he received a warm welcome from Sultan Selim when he arrived back at Constantinople in December 1798. This must at least in part have been due to the expert diplomatic skills of his brother Spencer Smith, who had recently negotiated the Treaty of Friendship between Britain and the Porte.

5

In fact, the sultan proved so captivated by the return of his friend that he gave Sidney Smith charge of the entire Turkish land and sea forces which were being assembled with the aim of driving the French out of the Levant, and appointed him a member of his

divan

, an unprecedented honor for a foreigner. Smith suggested that his friend Phélippeaux be made a colonel in the Turkish army, a request which was generously granted, and in a characteristic gesture he also requested the release of forty French galley slaves, in recognition of the gentlemanly treatment he had received from the prison governor of the Temple.

Calling himself Commodore Smith, a rank to which he was not en titled, Smith set sail in the

Tigre

for the Mediterranean. After making contact with the British navy, he clashed with Nelson over who precisely was in charge of Britain’s Mediterranean fleet, and then sailed to Alexandria, where in early March 1799 he took over command of the blockading British squadron (thus officially qualifying for the rank of commodore). Within days of his arrival he received an intelligence report that Napoleon had taken Jaffa and was marching on Acre. He immediately dispatched Phélippeaux on the

Theseus

to Acre, to liaise with Djezzar. Phélippeaux used his aristocratic charm, reinforced by his newly acquired commission in the Turkish army, to overcome Djezzar’s visceral hatred of the French. He managed to dissuade the worried pasha from abandoning his stronghold, assuring him that help was on the way in the shape of a British naval squadron, aided by Turkish warships. After a tour of inspection of the city’s defenses, Phélippeaux made use of his considerable military talents to suggest reinforcements and improvements.

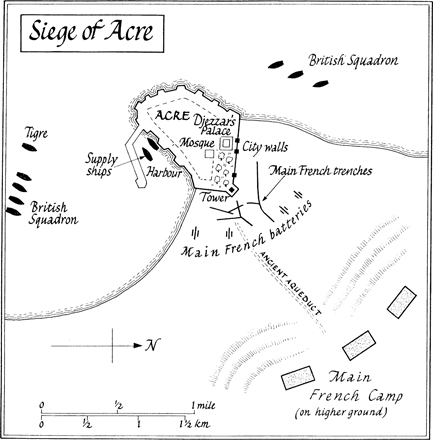

Acre was built on a peninsula jutting out into the sea in such a way as to protect the harbor below its southern walls. Facing the landward side was a crenellated wall incorporating a number of defensive towers. From inside the walls rose the dome and minaret of the main mosque, clumps of palm trees and the walls of Djezzar’s palace, which emerged out of the cramped maze of narrow streets and ramshackle low rooftops. Along the defensive wall some 250 guns were positioned to fire on the enemy on the plain below.