Nat Tate: An American Artist: 1928-1960 (2 page)

Read Nat Tate: An American Artist: 1928-1960 Online

Authors: William Boyd

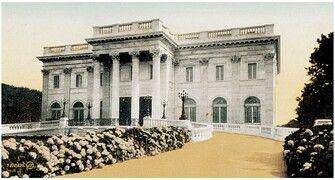

He bought a small but elegant summer house, Windrose, on the north fork of Long Island, where he and Irina lived in some style. Windrose was a curiosity: built in the 1890s, it was loosely modelled on the Petit Trianon and was designed by an architect called Fairfield Douglas who had worked for a while in the firm of Richard Morris Hunt. Barkasian had two long wings added in the same white stucco, neo-classical manner, had the garden re-landscaped and a small hill bull-dozed flat to afford a better southern view of Peconic Bay.

Windrose, Fairfield Douglas

More than two thousand trees and ornamental shrubs were planted. His ‘retirement’ was to be in the grandest style. The couple were childless: Irina concerned herself with local charities; Peter, cash rich in the Depression, travelled to New York once a week, where he diligently managed his portfolio of stocks and shares and established a small reputation as a connoisseur and collector – Tiffany lamps were his particular passion, but he also bought and sold pictures in a modest way and he had a fine collection of John Marin watercolours.

The eastern reaches of Long Island in the 1930s presented a picture of bleakness and deprivation: flat potato fields and isolated village communities of clam and scallop fishers, many of which still did not have electricity. Here and there were pockets of more cosmopolitan activity. East Hampton and Amagansett, on the south shore, had been attracting artists for decades, but Peconic, on the north of the bay, was on the wrong side of the tracks, artistically speaking, or ‘below the bridge’, as the local expression ran. Windrose seemed to be a rich man’s folly, but Peter Barkasian did not care: it was his own world, bought and paid for.

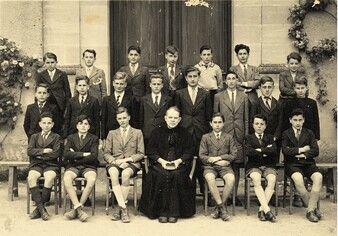

Nat Tate, aged sixteen, at Briarcliff, middle row, fourth from the right

Mary Tate was killed by a speeding delivery van as she stepped out of a drugstore in Riverhead, Long Island, one February morning in 1936. Nat was eight years old. He recalled to Mountstuart that he learnt of his mother’s death when a boy leaned out of a window overlooking the schoolyard where he was playing and bawled, ‘Hey, Tate, your mom’s been run over by a truck.’ He thought it was a cruel joke, shrugged and carried on with his softball game. It was only when he saw the headmaster grimly crossing the playground towards him that he realised he was an orphan.

It was natural – inevitable? – that the Barkasians should adopt Mary Tate’s orphan boy; it was also Nat Tate’s first substantial stroke of good fortune, if the enormous personal tragedy of the loss of one’s mother can be looked at in such a way. Little is known of the next few years, unfamiliarly cossetted and privileged as they must have been. ‘I hated my adolescence,’ he once cryptically told Mountstuart, ‘all spunk and shame’, and he never talked much about his teenage years or about the boarding school he was sent to – Briarcliff in Connecticut, now defunct. There is a poignant and touching photograph of him at home in Peconic on a holiday (it can’t have been long after his mother’s death). The boy, standing on a lawn, awkward, arms akimbo, looking away from the camera, the new soccer ball on the grass between his feet, perhaps kicked over towards him by a genial Peter Barkasian, learning to be a ‘Dad’. A few years later (in 1944) a more formal pose reveals the sixteen-year-old standing behind the left shoulder of the Dean of Briarcliff (Reverend Davis Trigg). Nat’s unsmiling face, plump with puppy fat, this time seems to stare out at the camera resentfully, his thick butter-blond hair scraped back from his forehead in a damp, disciplined lick.

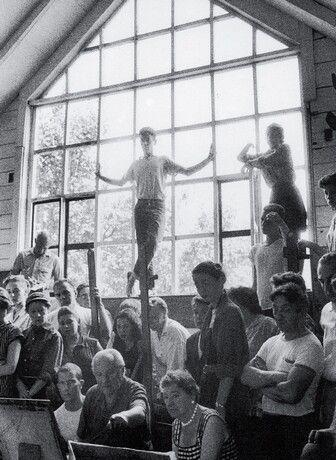

Academically, Nat did not excel. The only subject that engaged him was art, or ‘Paint and Drawing’ as it was known at Briarcliff. Nat did graduate but his grades were disappointing – only in ‘Paint and Drawing’ was he an ‘A’ student. And at this stage of his life his second stroke of luck occurred. Keen to capitalise on any vestige of a gift that his son might display, Peter Barkasian managed to have Nat enrolled in an art school, the celebrated Hofmann Summer School – which moved from its downtown Manhattan base each summer to Provincetown, Massachusetts. Nat never attended classes at West 9th Street in Manhattan, but for the four summers of 1947–51 he studied under the eccentric but vigorously modern tutelage of Hans Hofmann in the small fishing village on Cape Cod Bay.

Hans Hofmann’s Summer School in Provincetown, 1956. Photograph by Arnold Newman

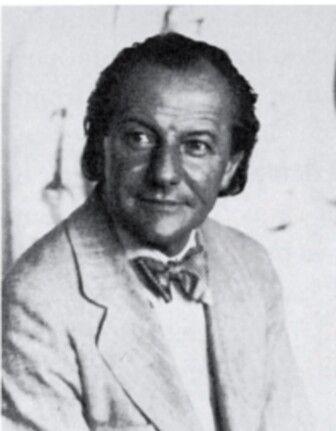

Hans Hofmann was a German émigré who had come to America in 1930. A big, blustering man with an adamantine ego and sense of mission, he was steeped in European Modernism and armed with redoubtable and abstruse theories about the integrity of the two-dimensional plane of the canvas. Its ‘flatness’ was its defining feature, and the artist’s sole task was to respect this as he arranged his coloured pigments upon it. Paint was ‘inert’, representation was wrongheaded, abstraction was God. In the ’40s and the ’50s, Hofmann’s dogmatic asseverations, delivered at his art school in downtown Manhattan and in the summer in Provincetown, profoundly influenced a whole generation of American artists.

At Provincetown, Nat Tate was still socially ill-at-ease during those Cape Cod summers, shy and unsure of himself. He did not mix much with the other students, guilty, so he told Mountstuart, about being so well off, and he is barely remembered by any of the school’s more celebrated alumni. He dressed soberly, almost old-fashionedly, in jackets and ties (a habit he was never fully to abandon), worked hard and, out of classroom hours, kept himself largely to himself.

Hans Hofmann

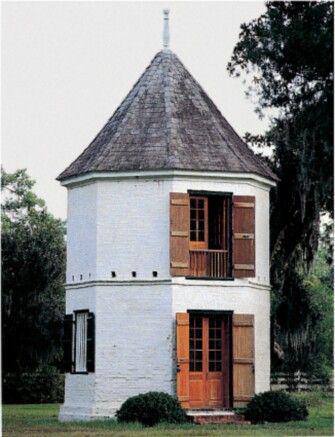

For the rest of the year he lived with the Barkasians. Peter was excited by the genuine talent that Nat was showing, and for the first time, one senses, he truly began to take an interest in his adopted son, renovating and transforming a small summer-house in the garden at Windrose, which Nat used as a studio and den. Logan Mountstuart observed that ‘although Nat has two parents he only ever talks about Peter – Peter this, Peter that – Irina was there, somewhere, but always in the distant background; it was as if, now Nat had left school, her role was over and Peter stepped in.’ Janet Felzer, in a letter to Mountstuart in 1961, put it more bluntly: ‘the fact was that during the Provincetown years Peter B. slowly but surely fell in love with his son.’

Nat Tate’s studio at Windrose

Whether Felzer’s assessment is true or false, the relationship between the two grew closer. Peter Barkasian paid Nat a generous monthly allowance in return for which he was given all the art that Nat wished to see preserved. In 1950 Barkasian began to catalogue every sketch and painting he received. Each work was labelled, dated and, if not hung, was stored carefully away in a strong room in the main house. Felzer again: ‘Peter thought he had a genius working at the bottom of the garden – so he started to log and collect his output for posterity.’

No one knows when Nat Tate began his

Bridge

sequence of drawings, or why he was so taken with the Hart Crane poem

3

. The best guess puts it some time in 1950. Certainly by the time Janet Felzer first saw some of the drawings in 1952 their numberings were already up in the eighties and nineties.

Felzer was driving back from Long Island to New York – she had been weekending in Southampton – with the poet and critic Frank O’Hara. They stopped for a drink in Islip and, killing some time, wandered into a local gallery there, which happened to be run by a friend of Peter Barkasian (from whom Barkasian had bought two Winslow Homer watercolours, it seemed). Half a dozen of Nat Tate’s

Bridge

drawings were hung in a back room.