Nat Tate: An American Artist: 1928-1960 (7 page)

Read Nat Tate: An American Artist: 1928-1960 Online

Authors: William Boyd

Hart Crane, portrait by David Alfaro Siqueiros, from The Hart Crane Collection, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University, New York

Logan Mountstuart’s journal:

. . . the place was immaculate, tidy and ordered. In the kitchen glasses were clean and stacked, wastepaper baskets had been emptied. In the studio we saw one large canvas placed against the wall, obviously recently started, a crosshatched mass of bruised blues, purples and blacks. Its title

Orizaba/Return to Union Beach

was scrawled on the back and neither Janet or Barkasian picked up the reference. I told them that ‘Orizaba’ was the name of the ship that was carrying Hart Crane home from Havana on his last fatal journey in 1932. ‘Fatal?’ Barkasian said. ‘How did he die?’ Janet shrugged. I felt I had to tell him: ‘He drowned,’ I said, ‘he jumped overboard.’ Barkasian was shocked, driven to tears: the painting, inchoate and mystifying, was suddenly the only suicide note available. If poor Nat could not have contrived to live his life as an artist he at least ensured that the symbolic weight of its end was apt and to be duly noted.

Why did Nat Tate kill himself? What made him throw himself into the icy confluence of the Hudson and the East River that January day in 1960? There are many theories, some glib, some complex. Mountstuart decided initially that he had fallen into a depression, drink-fuelled perhaps – ‘simply gone barking mad’ – and decided to kill himself. Janet Felzer considered that there was a deeper insecurity: she always suspected something had in fact occurred between Barkasian and van Taller, some deal had been struck – which Barkasian had denied but which, perhaps, Nat had unwittingly unearthed. This was the only way she could account for the almost wholesale destruction of his work. There was a desire there to frustrate Barkasian from beyond the grave, to punish him for an unforgivable betrayal.

Standing there in Alice Singer’s gallery, thirty-seven years later, looking at

Bridge no. 122

, one of perhaps a dozen works by Nat Tate that survive (and wondering if it had once been one of Logan Mountstuart’s), I thought that the mystery of Nat Tate’s untimely death was explained perhaps by all of these answers, and more. Nat Tate had a talent, for sure, an uncertain gift, but perhaps he knew in the core of his being that it did not amount to much. Van Taller’s arrival was the presaging of a future he did not welcome. Tate was one of those rare artists who did not need, and did not seek, the transformation of his painting into a valuable commodity to be bought and sold on the whim of a market and its marketeers. He had seen the future and it stank.

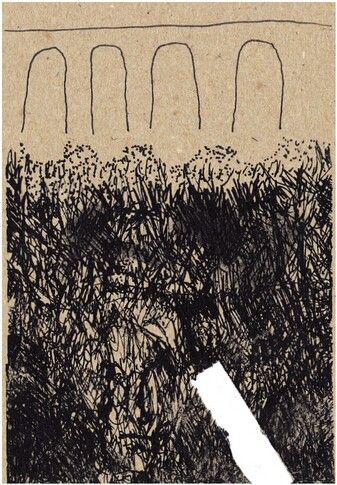

Un-numbered

Bridge

drawing, 1959. Private Collection

Larry Rivers giving the oration at Frank O’Hara’s funeral, July 28, 1966. Logan Mountstuart, present amongst the two hundred mourners, wrote: ‘a blazing, stifling hot day. Bizarre sight of hundreds of people in sunglasses. Larry’s speech surprisingly affecting. It was as if we all felt some kind of full stop had been made to our era. Nat Tate dead at 32. O’Hara at 40. I suppose they will become our plaster saints – something to be said for dying young.’

My own feeling is that the meeting with Braque and the opportunity to see some of Braque’s great final paintings removed the last supports from a person and a personality that was, by all accounts, a fragile one, however charming and easy on the eye. The example of a truly great artist at the summit of his powers will – and perhaps should – have a daunting effect on a lesser talent, particularly one still finding its way. The difference in the case of Nat Tate was that it was not so much awe or reverence or a natural sense of inadequacy that he felt – as shame. And shame was an emotion he found impossible to live with.

Logan Mountstuart later softened his brutal diagnosis, realising there were too many signs and signals about Nat’s final acts for them to be incoherent and deranged. He cited the quiet guile employed in reclaiming the work, the thoroughgoing and systematic destruction of everything he could lay his hands on (99 per cent, Felzer ruefully calculated), the careful positioning of the incomplete

Orizaba

canvas with its encoded Hart Crane message, even the choice of death and its location. ‘He is one whose name is writ on water,’ Mountstuart commented a year or so after Nat Tate’s death – very wisely, I think. ‘It was all about drowning, in the end, I’m sure. Nat was drowning – literally and figuratively – and so he headed out to sea making for the Jersey shore where it all began, where he had been conceived, perhaps. There was in his suicide a great unhappy massing of symbols – of art, of blissful escape, of despair – and in his own desperate willed death by water lay a final bitter gesture towards the drowned father that he never knew.’

I would like to thank Sally Felzer for making available notes, photographs

and documentation that her late sister had compiled about Nat Tate. I am

grateful to the Alice Singer Gallery in New York, and Sander-Lynde Institute, Philadelphia, for permission to reproduce, respectively,

Bridge no. 122

and

Portrait of K

. The help and encouragement provided by Gudrun Ingridsdottir (administrator of the Estate of Logan Mountstuart) has been invaluable.

Logan Mountstuart: The Intimate Journals, edited by William Boyd, was published in September 1999.

Janet Felzer’s letters to Logan Mountstuart © the Estate of Logan Mountstuart 1997.

Hart Crane (1899–1932), American poet. Crane published only two collections of poetry in his lifetime, White Buildings (1926) and The Bridge (1930), but is still recognised as the outstanding poet of his generation. A neurotic, unstable personality, he became convinced that his creative talent had become dissipated, and he committed suicide by jumping from a ship that was bringing him home from a year’s residence in Mexico.

Letter to the author, 1997.

Letter to the author, 1997.

This account of Nat Tate’s last days was compiled by Janet Felzer in the year after his death.

Copyright © William Boyd 1998

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury USA, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them.

Published by Bloomsbury USA, New York

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: 978-1-60819-580-0 (hardcover)

This edition published by Bloomsbury USA in 2011

This e-book edition published in 2011

E-book ISBN: 978-1-60819-726-2