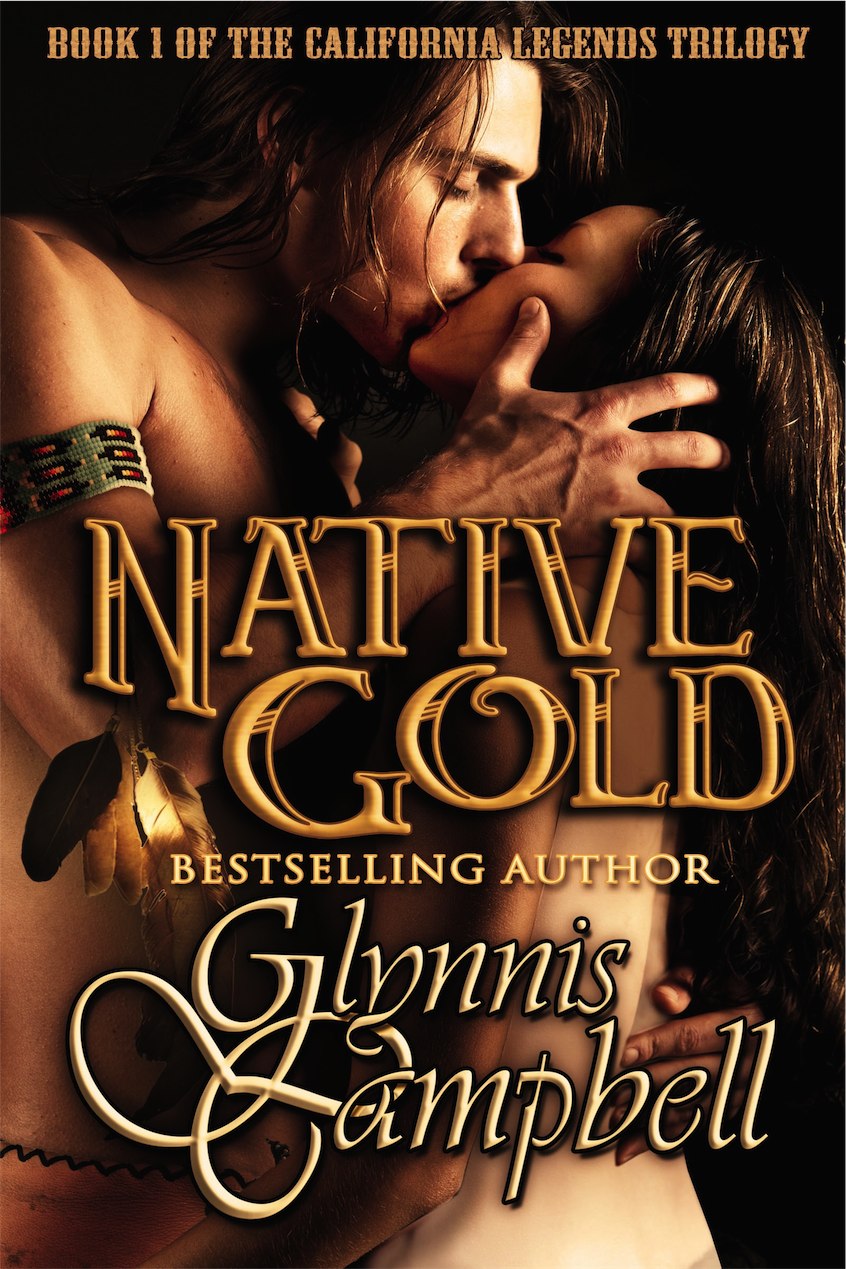

Native Gold

by Glynnis Campbell

Copyright 2014 Glynnis Campbell

Native Gold by Glynnis Campbell

Published by Glynnis Campbell

COPYRIGHT © Glynnis Campbell 2014

ISBN 9781938114113

1st Edition, October 2014

Produced with

Typesetter

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced or transmitted in any manner whatsoever, electronically, in print, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of both Glynnis Campbell and Glynnis Campbell, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

PUBLISHER'S NOTE: This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each reader. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

For the good people of Paradise

from the

Gold Nugget Queen of 1975

- Title Page

- Prologue

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Epilogue

- Thank You

AUTUMN 1850

NEW YORK

"Ladies and gentlemen, if you please!" Ambrose Hardwicke clapped his hands, earning the attention of the American nobility packed into his glittering ballroom.

Mattie creased the rose satin of her too-tight gown with her nail-bitten fingers. This was her moment.

It wasn’t the first time her uncle had paraded her before the cream of New York society. Ambrose never forgot his duties to his five charges—the four daughters who were his by blood, and seventeen-year-old Mathilda, who’d been thrust upon him as an orphan two years ago. Chief among those duties was seeing that his girls married well.

To marry well, Ambrose said, one had to possess Quality. Something Mattie apparently lacked. Something Ambrose worked hard to instill in her.

His four daughters, blessed with their mother’s beauty and poise, would grace the arm of any man he chose for them.

Mathilda, however, didn’t have their porcelain skin, pale gold tresses, or angelic features.

Some of her flaws were a matter of birth. Some of them she owed to her affection for the sun and her aversion to bonnets. Her complexion bordered on tawny. Her brown hair was streaked with lighter strands of a most contrary color, which were in startling contrast to her bright green eyes. And to everyone’s horror, she had a sprinkling of tiny freckles across her nose that no amount of powder could hide.

But worse than her appearance, according to Uncle Ambrose, was her temperament. She didn’t have her cousins’ gentle manner. She tended to speak before she was spoken to. And often, what came out of her mouth wasn’t suited to polite society.

So Ambrose had decided that wayward Mattie must be marketed by merit of what he regarded as her only gift—her talent for painting.

"If I may have your attention!" he bellowed.

Mattie chewed at her lower lip. Aunt Emily smiled tightly, sending her a chiding glare. Proper ladies didn’t fidget. None of her cousins, currently lined up in graceful ascending height beside their mother, ever moved a muscle that wasn’t absolutely essential. Even now, the sisters seemed to float above the hubbub of the evening unperturbed, like thistledown atop a swirling eddy.

Not Mattie. She was wound as tight as a clock spring.

It didn’t matter that Uncle Ambrose hosted these galas at least twice a season and that they always included a viewing of Mathilda’s latest work.

Tonight was different. Tonight she’d show the audience a masterpiece. Tonight she’d bare her soul.

This painting was the best she’d ever done. The image had emerged upon the canvas in a rush of passion, like a fevered outpouring from her heart. It seemed like she’d painted it with her own blood and tears.

A thrill of improper excitement coursed through her as she thought about what sat upon the easel beneath the velvet drape. This was no muted, delicate watercolor of the countryside. This painting would take their breath away. It would open their eyes, the way her eyes had been opened by the artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood—Millais, Rossetti, and Hunt—whose work she’d seen in London last year.

Just thinking of how those young artists had brazenly challenged the Royal Academy made her heart race.

They followed no rules but those of nature. Gone were the stifling standards of Sir Joshua Reynolds. Dead were the outdated concepts of the Renaissance.

Art was no longer slave to man, but expression to truth—a truth Mattie was about to reveal to the guests, who were silent now except for soft murmurs and the rustle of silk skirts.

"My niece informs me," Ambrose announced, smoothing one waxed tip of his gray mustache, "that she has abandoned landscapes this time in favor of a portrait."

A few polite ahs and approving nods were sent her way.

"She has chosen to paint, from recollection, her dearly departed parents—my brother, Lawrence, and his wife, Mary."

There were a few sympathetic whispers as he grasped the corner of the drape. Mattie held her breath. Then, in a dramatic sweep of velvet, he revealed the painting.

The crowd gasped, awestruck.

Mattie knew intimately every brush stroke, every shadow, each strand of hair and droplet of water, but the painting amazed even her. Had she truly done it herself? Or had the spirit of the Pre-Raphaelites possessed her soul, guiding her hand?

Her mother and father, lost at sea, she’d depicted in vibrant oils as a Siren and a sailor.

On the left, the nude female figure half-reclined upon stark black rock, her scaly fish tail barely visible beneath the swirling emerald depths of the sea, her pale bosom slashed by strands of her dark, wet hair. Her lips were parted as if in melancholy song, and her face appeared to glow with ethereal light.

Below her, the sailor, his shirt torn from his shoulders, his bronze hair drenched, his face tormented by wondrous obsession and fatigue, sank in the waters at her feet, one hand reaching up towards her in supplication.

Just looking at the painting, Mattie could feel their tragedy. Yet the scene spoke of hope as well. From the skies above the doomed pair, the somber clouds broke to reveal a single shimmering bolt of sunlight, a guiding beacon to heaven and happiness beyond.

So enrapt was she, reliving the emotion of the painting—sorrow, frustration, promise—that at first Mattie failed to hear the whispers. When they finally registered, she couldn’t have been more astonished.

"Good God!"

"What kind of daughter—“

"—not even a stitch of clothing!"

"Lawrence would turn in his grave if—“

"How could she—“

"Indecent, I tell you!"

The spell of the painting broken, Mattie turned a bewildered face to the crowd. Some of them stood with open mouths, as if she’d just unveiled a three-headed calf. Uncle Ambrose’s face turned ruddy, and he shook with outrage. And in the corner of the room, her perfectly composed cousin Diana fell over in a dead faint.

A full hour had passed since the debacle in the ballroom. Yet Mattie still waited, picking at the arm of the worn leather chair facing her uncle’s deserted desk in the library. Clearly he intended to let her stew until all the guests departed before he came, as he’d promised, "to deal with her." She wondered if he made his petitioners fidget in this chair before they begged him for a morsel of his considerable funds.

She chewed at her lip. She didn’t understand why everyone had reacted so badly to her work. Surely Diana’s swooning had less to do with what she’d seen on the canvas than with the tightness of her stays—which was a perfect example of what the Pre-Raphaelites fought against. Restraint was a thing of the past. Constriction of one’s artistic expression made no more sense than the wasp-waisted devices of torture women endured in the name of fashion.

Yes, she thought, scooting the chair back with a harsh scrape. That was it. She’d explain it all to her uncle when he came to speak to her.

If

he ever came.

She rubbed a damp palm over the arm of the chair, then pushed herself up again and began pacing. Had the Brothers faced such scorn when they first presented their paintings to the public? She supposed she’d have to inure herself to criticism if she wanted to ascend to their prominence in the art world. For above all—as her parents had told her from the time she was old enough to hold a paintbrush—she must never fight her nature. She must be true to herself.