Native Seattle (39 page)

32

Aerial Duck Net

túqap (lit. ‘blocked at bottom’)

This is a common place-name in Puget Sound, referring to nets that were strung between tall poles and used to catch waterfowl. This unique technology mystified British explorer George Vancouver, who wrote that it was “undoubtedly, intended to answer some particular purpose; but whether of a religious, civil, or military nature, must be left to some future investigation.”

17

Waterman was told that the ducks

would be “started up” at Lake Union, then caught in the net here. One of Harrington's informants, Percival, had camped here regularly before the site was urbanized and recalled that a small creek ran year-round at the site. This place-name can also describe someone who is constipated.

33

Little Prairie

babáqWab

or

Large Prairie

báqWbaqWab

Indian witnesses in a land claims case in the 1920s identified this place as the site of two longhouses, each 48 by 96 feet. The residents of these houses would have made good use of the large patches of salal (

Gaultheria shallon

) that could be found here, either eating the fruit fresh or drying it into cakes for the winter. Middens found along the shoreline here attest to the area's importance as a shellfish-processing site as well. Settler William Bell staked his claim here, and until the early twentieth century, the Belltown shoreline was an important camping place for Native people, including migrants from Alaska, British Columbia, and Washington's outer coast.

34

Sour Water

scHapaqW

Harrington collected this name for a hole in the sand that could be seen at low tide, about two blocks north of the foot of Pike Street. His informants told him that the hole was believed to connect via an underground channel to Lake Union. Young whales were said to have swum through the tunnel to the lake. A similar story is told about entry 116, and in fact, stories of such subterranean waterways abound throughout the region.

18

35

Spring

bóólatS

This spring, located on what would become Arthur Denny's homestead, was likely a less important source of freshwater for indigenous people, since it had the same unadorned designation as entry 27. Had it been more significant, it likely would have had a name like those for 58 and

99. This spring and others inspired the names of Spring Street and the Spring Hill Water Company, Seattle's first municipal water supply, which was organized in 1881.

19

36

Grounds of the Leader's Camp

QulXáqabeexW

This place-name is said by Harrington to be the ‘chief place’ and another name for ‘Seattle’. Most likely this was the name for a camp of a man known as either Kelly or Seattle Curley (Soowalt), who was the headman of the Duwamish village in what is now downtown Seattle. He was a brother of Seeathl. His camp was located between Columbia and Cherry streets and First and Second avenues by one source but closer to Seneca or Spring by others. This camp also appears in the Phelps map of the Battle of Seattle, reproduced elsewhere in this book.

20

37

Little Crossing-Over Place

sdZéédZul7aleecH (lit. ‘little crossing of the back’)

The name refers to a small portage. Up to eight longhouses once existed here; only the ruins of one remained when Seattle was founded in 1852. Waterman penned his informant's description of the site as follows: “In the vicinity of the present King Street Station in the city of Seattle, there was formerly a little promontory with a lagoon behind it. On the promontory were a few trees. Behind this clump of trees a trail led from the beach over to the lagoon, which gave rise to the name. There was an Indian village on each side of this promontory. Flounders were plentiful in the lagoon. This [the tidal marsh] is exactly where the King Street Station now stands.”

21

According to other informants who worked with amateur ethnographer Arthur Ballard, this village was located at the foot of Yesler Way. If that were the case, the name would refer to the trail that crossed over the hill to Lake Washington in what is now the Leschi neighborhood.

Pioneer daughter Sophie Frye Bass described a second trail that came down to the Sound here: from the Renton area, it “straggled on to Rainier Valley and approximately along Rainier Avenue, then zigzagged across Jackson, Main, and King Streets to salt chuck (water).”

22

Until at least the Second World War, Whulshootseed speakers used this name when referring to the modern city of Seattle.

38

Greenish-Yellow Spine

qWátSéécH

This name for Beacon Hill may refer to the color of the hillsides; General Land Office survey field notes from the 1850s show that many maples, alders, and other deciduous trees grew here.

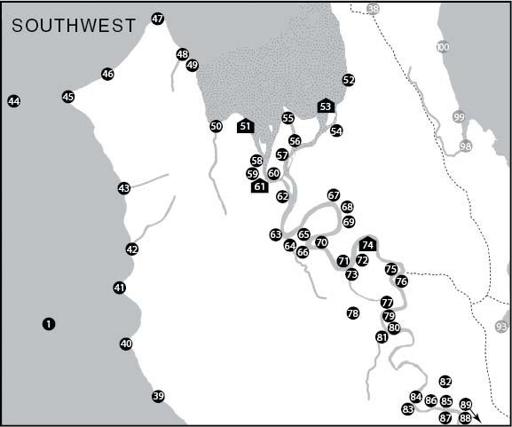

Map 2: Southwest

This time we arrive from the south (from up the Sound), following the West Seattle coastline and curving around into the estuary of the Duwamish River. These waters connected the Duwamish people with not only other Puget Sound Salish tribes such as the Suquamish and Snohomish but also more distant Coast Salish groups like the Twana of Hood Canal. Then we enter the lower valley of the Duwamish River, where the intensity of environmental transformation is matched by the intensity and density of indigenous inhabitance. The farther upriver we go, the closer we get to the core territories of the Duwamish proper. Beyond them lay the lands of the Stkamish, a group that became part of the present-day Muckleshoot Tribe.

39

Place of Scorched Bluff

dxWKWásoos

The bluffs here had black markings, hence the name. Such descriptive terms were critical for travelers on the Sound, who typically described and conducted long voyages in terms of the number of points that were passed during the journey rather than time or a consistent unit of measurement.

23

40

It Has Changes-Its-Face

bas7ayáhoos

Brace Point is one of two places in Seattle that was inhabited by a horned snake, one of the most powerful spirits used by indigenous healers. (The other site is 100.) The large red boulder on the shoreline here was also associated with the spirit power; some people believed the boulder could change its shape and that anyone who looked at it would be twisted into a knot.

41

Tight Bluff

CHuXáydoos

This former name of Point Williams describes the dense plant growth on this headland and helped distinguish it from other points in the promontory-based system of measurement described at entry 39. It is now the site of Lincoln Park.

42

Capsized

gWul

This inauspiciously named creek enters Puget Sound at the north end of Lincoln Park. The old name might be a warning about the offshore potential for the tipping of a canoe.

43

Rids the Cold

Túsbud (lit. ‘implement for ridding cold’)

While the name of this site may be a reference to the battle of the winds described at entries 82–88, since the fleeing North Wind was known to have alighted briefly at other places along the Sound, it is more likely a reference to the bricks that were made out of clay here by settlers very early in Seattle's development. Native people would certainly have been aware of the insulating properties of brick, even if they could rarely afford to build their houses out of the new material.

44

Wealth Spirit

teeyóóhLbaX

Jacob Wahalchoo, a signatory of the Treaty of Point Elliott, dove beneath the waters of Puget Sound here in search of a spirit power that lived in

a huge underwater longhouse. This power brought wealth and generosity to those who held it. It could cause neighboring families to offer their daughters in marriage without asking a bride-price or could make game drop dead at its holder's door during winter dances.

24

45

Prairie Point

sbaqWábaqs

An island connected to the mainland by two sandspits—a double tombolo—this windswept place remains the birthplace of Seattle in popular memory but was an indigenous place and point of colonial reconnaissance well before 1851. Prairies here were almost certainly maintained through seasonal burning by indigenous cultivators. Pressings of plants from this prairie, most now extirpated from Seattle, can be found in the University of Washington's botanical collections.

46

Place That Became Wet

dxWqWóótoob

or

Place for Reeds

dxWkóót7ee

Waterman and Harrington collected two different versions of the name for this place. Luckily, they seem to corroborate each other in terms of what kind of place it was: a wetland rich with resources such as highbush cranberries (

Vaccinium oxycoccus

), which were eaten fresh and dried, and cattails (

Typha latifolia

), which were used in fabricating mats. Many of Seattle's upland areas, especially the West Seattle peninsula and the Greenwood neighborhood, were filled with wetlands and bogs. One such bog is currently being restored near this site, at Roxbury Park at the headwaters of Longfellow Creek.

47

Low Point

sgWudaqs

This ancient name for Duwamish Head can also mean ‘base of the point’. This beach was an important fishing site; it was here that Captain Robert Fay tried to establish a commercial fishery employing men recruited by Seeathl. According to Duwamish elder Alice Cross, there was once a large boulder covered with petroglyphs on the beach near here, each carving symbolizing a spirit power employed by local shamans.

25

48

Place of Waterfalls

dxWtSútXood (lit. ‘where water falls over a bank’)

Shell middens have been found all along the shoreline near this steep gully.

49

Caved-In

asleeQW

As in many places around Seattle, the bluffs here are very unstable. In fact, this part of the West Seattle landscape continues to live up to its indigenous name, with elaborate restraints only partially able to keep the land from moving during small earthquakes or periods of heavy rain.

50

Smelt

t7áWee

This is a local form of the word for smelt,

Hypomesus pretiosus;

elsewhere around Puget Sound it was called

ChaW

or

ChaWoo

. The indigenous name for Longfellow Creek suggests a traditional fishery. Carbon dating of the remains of an old shellfish gathering and fishing campsite here shows it was in use as far back as the fourteenth century. Today, local residents are struggling to restore the creek and its salmon runs; despite their efforts in the upper watershed, the old estuary is still straddled by industrial development, most notably a busy foundry. Smelt, meanwhile, have largely disappeared from Elliott Bay: the shallow-sloped gravel beaches with freshwater seepage, upon which they depend for spawning, have almost all been destroyed by development.

51

Herring's House

Tóó7ool7altxW

This was an important town; it included at least four longhouses and an enormous potlatch house, and middens have been found throughout this area. Important figures residing here included a headman named Tsootsalptud and a shaman called Bookelatqw. Two sisters-inlaw of Big John, an important informant and early fishing-rights advocate among the Skwupabsh (Green River People, who lived upriver from Auburn), came from this village as well. The burning of Herring's House in 1893 is one of the few times when the destruction of indigenous Puget Sound settlements by Americans appeared in the official historical record. Its name has since been applied to a city park along the Duwamish River, located at the site of entry 61.

52

Burned-Off Place

dxWpásHtub

This small spit at the foot of Beacon Hill was likely an ideal place for camping, and its name suggests there may have been a small cultivated prairie here as well. Billy and Ellen Phillips, a Duwamish Indian couple, managed to eke out a living at the foot of nearby Stacy Street until 1910.

53

Little-Bit-Straight Point

tutúhLaqs

Waterman recorded this small promontory on an island as the location of a small stockade and lookout, used to defend settlements farther upriver. During a land claims case in the 1920s, however, Duwamish and Muckleshoot elder Major Hamilton testified that three longhouses had also once been located here. Long buried under fill, the site is near the old Rainier Brewery along Interstate 5.

26

54

Canoe Opening

slóóweehL

This word, like its diminutive form (108), has two meanings. It can refer to the tiny holes made in canoes during carving to help measure hull thickness. Informants told Waterman with respect to this site that the name refers to channels, or ‘canoe-passes’, in the grassy marsh through which canoes can be pushed to effect a shortcut.

55

A Cut

XWuQ

This was the widest of the several mouths of the Duwamish River, which once carried the commingled flows of the White, Green, Black, Cedar, and Sammamish rivers. Today, only the waters of the Green enter Elliott Bay.