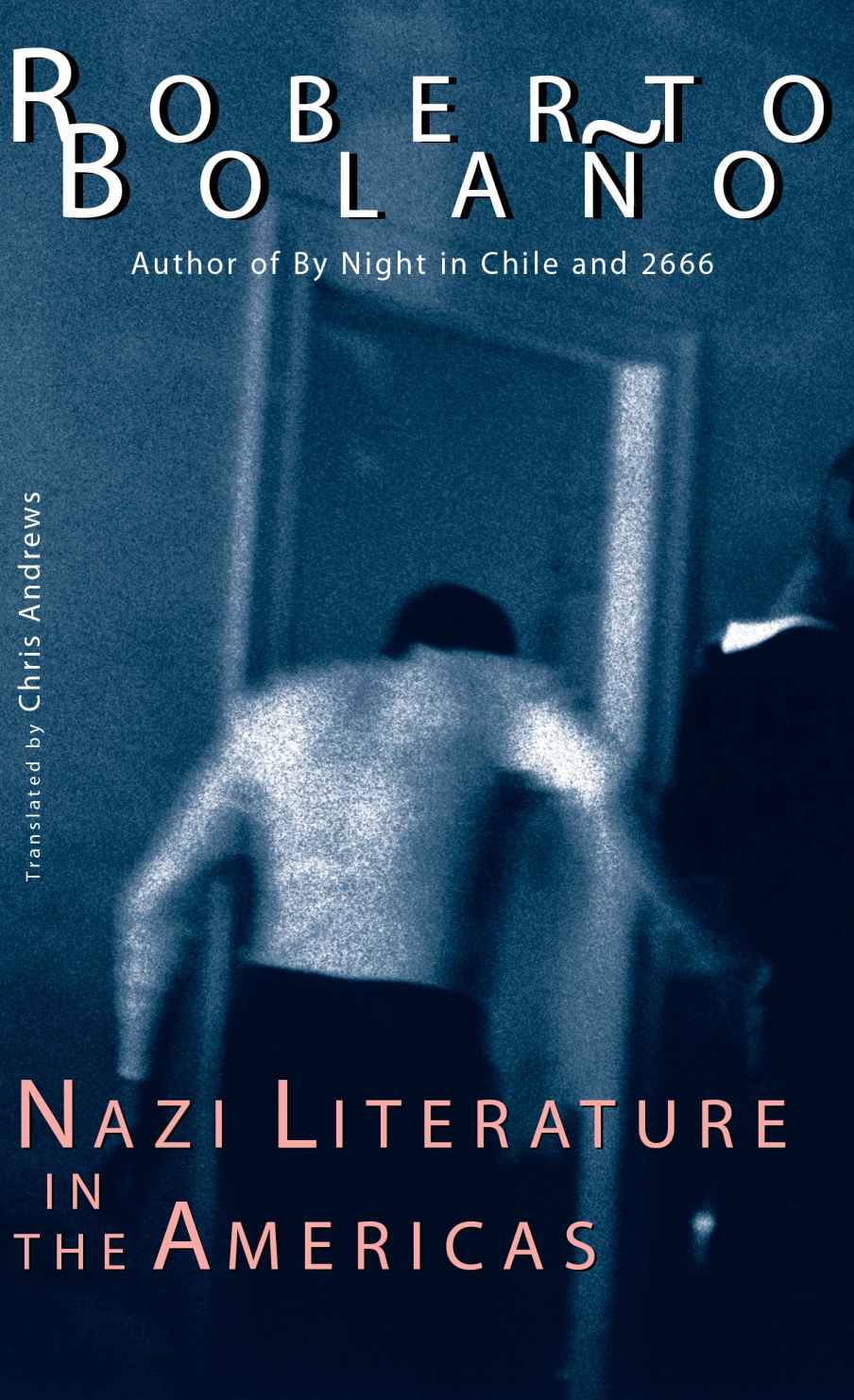

Nazi Literature in the Americas (New Directions Paperbook)

Read Nazi Literature in the Americas (New Directions Paperbook) Online

Authors: Roberto Bolaño

Roberto Bolaño

Nazi Literature in the Americas

Translated by C

HRIS

A

NDREWS

A NEW DIRECTIONS BOOK

for Carolina López

Contents

Edelmira Thompson de Mendiluce

Itinerant Heroes or the Fragility of Mirrors

Forerunners and Figures of the Anti-Enlightenment

Andrés Cepeda Cepeda, known as

The Page

Two Germans at the Ends of the Earth

Speculative and Science Fiction

Magicians, Mercernaries and Miserable Creatures

The Many Masks of Max Mirebalais

Max Mirebalais, alias

Max Kasimir, Max von Hauptman, Max Le

Gueule, Jacques Artibonito

Thomas R. Murchison, alias

The Texan

Argentino Schiaffino, alias

Fatso

If the flow is slow enough and you have a good bicycle, or a horse, it

is

possible to bathe twice (or even three times, should your personal

hygiene so require) in the same river.

Augusto Monterroso

THE MENDILUCE CLAN

E

DELMIRA

T

HOMPSON DE

M

ENDILUCE

Buenos Aires, 1894–Buenos Aires, 1993

A

t fifteen, Edelmira

Thompson published her first book,

To Daddy

, which earned her a modest

place in the vast gallery of lady poets active in Buenos Aires high society. And

from then on, she was a regular presence in the salons of Ximena San Diego and

Susana Lezcano Lafinur, dictators of taste in poetry, and of taste in general,

on both banks of the Río de la Plata at the dawn of the twentieth century. Her

first poems, as one might reasonably have guessed, were concerned with filial

piety, religious meditation and gardens. She flirted with the idea of taking the

veil. She learned to ride.

In 1917 she met the rancher and entrepreneur Sebastian Mendiluce,

twenty years her senior. Everyone was surprised when they announced their

engagement, after only a few months. According to people who knew him at the

time, Mendiluce thought little of literature in general and poetry in

particular, had no artistic sensibility (although he did occasionally go to the

opera), and his conversation was on a par with that of his farmhands and factory

workers. He was tall and energetic, but not handsome by any means. There was,

however, no disputing his inexhaustible wealth.

Edelmira Thompson’s friends considered it a marriage of convenience,

but in fact she married for love. A love that neither she nor Mendiluce was ever

able to explain and which endured imperturbably all the days of her life.

Marriage, which ends the careers of so many promising women writers,

quickened the pen of Edelmira Thompson. She established a salon in Buenos Aires

to rival those of the redoubtable Ximena San Diego and Susana Lezcano Lafinur.

She took young Argentinean painters under her wing, not only buying their work

(in 1950 her collection of paintings and sculptures was, if not the best in the

Republic, certainly one of the largest and most extravagant), but also inviting

them to paint at her ranch in Azul, far from the madding crowd, all expenses

paid. She founded a publishing house, The Lamp of the South, which brought out

more than fifty books of poetry, many of which were dedicated to Edelmira

herself, “the fairy godmother of Argentinean letters.”

In 1921 she published her first book of prose,

All My Life

,

an idyllic and rather flat autobiography, devoid of gossip, full of landscapes

and poetic meditations. Contrary to the author’s expectations, it disappeared

from the bookshop windows in Buenos Aires without leaving so much as a ripple.

Disappointed, Edelmira set off for Europe with her two small sons, two servants,

and more than twenty suitcases.

She visited Lourdes and the great cathedrals. She had an audience with

the Pope. A yacht took her from island to island in the Aegean. She reached

Crete one midday in spring. In 1922, in Paris, she published a book of

children’s verse in French, and another in Spanish. Then she returned to

Argentina.

But things had changed, and Edelmira did not feel at ease in her

country. Her new book of poems (

European Hours

, 1923) was described in

a local newspaper as “precious.” The nation’s most influential reviewer, Dr.

Enrique Belmar, described her as “an idle, childish lady whose time and energy

would be better spent on good works, such as educating all the ragged little

rascals on the loose throughout this vast land of ours.” Edelmira’s elegant

reply consisted of an invitation to attend her salon, addressed to Belmar and

other critics, which was ignored by all but four half-starved gossip columnists

and crime reporters. Humiliated, she retired to her ranch in Azul, accompanied

by a faithful few. Soothed by the rural calm and the conversations of simple,

hardworking country folk, she set to work on the new book of poetry that was to

be her vindication.

Argentinean Hours

(1925) sparked scandal and

controversy from the day of its publication. In her new poems, Edelmira

renounced contemplative vision in favor of pugnacious action. She attacked

Argentina’s critics and literary ladies, the decadence besetting the nation’s

cultural life. She argued for a return to origins: agrarian labor and the

still-wild southern frontier. Flirting and swooning were behind her now.

Edelmira longed for the epic and its proportions, a literature unafraid to face

the challenge of singing the fatherland. One way and another, the book was a

great success, but, demonstrating her humility, Edelmira barely took the time to

relish her triumph, and soon left for Europe once again. She was accompanied by

her children, her servants, and the Buenos Aires philosopher Aldo Carozzone, who

acted as her personal secretary.

She spent the year 1926 traveling in Italy with her numerous

entourage. In 1927, she was joined by Mendiluce. In 1928, her first daughter,

Luz, a bouncing, ten-pound baby, was born in Berlin. The German philosopher

Haushofer was godfather to the child, and the baptism, attended by the cream of

the German and Argentinean intelligentsia, was followed by three days of

non-stop festivities, which culminated in a little wood near Rathenow, where the

Mendiluces treated Haushofer to a kettledrum solo composed and performed by

maestro Tito Vásquez, who went on to become a sensation.

In 1929, the stock-market crash obliged Sebastian Mendiluce to return

to Argentina. Meanwhile Edelmira and her children were presented to Adolf

Hitler, who held Luz and said, “She certainly is a wonderful little girl.”

Photos were taken. The future Führer of the Reich made a great impression on the

Argentinean poet. Before leaving, she presented him with several of her own

books and a deluxe edition of

Martin Fierro

. Hitler thanked her warmly,

beseeching her to translate one of her poems into German on the spot, a task

which, with the help of Carozzone, she managed to accomplish. Hitler was clearly

delighted. The lines were resounding and looked to the future. In high spirits,

Edelmira asked for the Führer’s advice: which would be the most appropriate

school for her sons? He recommended a Swiss boarding school, but added that the

best school was life itself. By the end of the audience, Edelmira and Carozzone

were committed Hitlerites.

1930 was a year of voyages and adventures. Accompanied by Carozzone,

her young daughter (the boys were boarding at an exclusive school in Berne) and

her two Indian servants, Edelmira traveled up and down the Nile, visited

Jerusalem (where she had a mystical experience or a nervous breakdown, which

confined her to a hotel bed for three days), then Damascus, Baghdad . . .

Her head was buzzing with projects: she planned to launch a new

publishing house back in Buenos Aires, which would specialize in translations of

European thinkers and novelists; she dreamed of studying architecture and

designing grandiose schools to be built in parts of the country as yet untouched

by civilization; she wanted to set up a foundation in memory of her mother, with

the mission of helping young women from poor backgrounds to fulfill their

artistic aspirations. And little by little a new book began to take shape in her

mind.

In 1931 she returned to the Argentinean capital and began to carry out

her projects. She launched a magazine,

Modern Argentina

, edited by

Carozzone, whose mission was to publish the latest in poetry and fiction, but

also political commentary, philosophical essays, film reviews, and articles on

social issues. Half of the first number was devoted to Edelmira’s book

The

New Spring

, which came out simultaneously. Part travel narrative, part

philosophical memoir, the book reflected on the state of the world, and the

destinies of Europe and America in particular, while warning of the threat that

Communism posed to Christian civilization.

The following years were rich and productive: she wrote new books,

made new friends, traveled to new places (touring the north of Argentina, she

crossed the Bolivian border on horseback), launched new publishing ventures, and

diversified her artistic activity, writing the libretto for an opera (

Ana,

the Peasant Redeemed

, 1935, whose première at the Teatro Colón divided

the public and led to verbal and physical confrontations), painting a series of

landscapes in the province of Buenos Aires, and collaborating in the production

of three plays by the Uruguayan author Wenceslao Hassel.

When Sebastian Mendiluce died, in 1940, Edelmira was unable to travel

to Europe, as she would have wished, because of the war. Deranged by sorrow, she

composed a death notice which took up a whole page in each of the nation’s major

newspapers, and was signed: Edelmira, the widow Mendiluce. The text no doubt

reflected her unstable mental state. It was widely mocked and derided among the

Argentinean intelligentsia.

Once again, she withdrew to her ranch in Azul, accompanied only by her

daughter, the faithful Carozzone, and a young painter named Atilio Franchetti.

In the mornings she wrote or painted. Her afternoons were occupied by long

solitary walks or hours of reading. Reading and a bent for interior design gave

rise to her finest work,

Poe’s Room

(1944), which prefigured the

nouveau roman

and much subsequent avant-garde writing, and earned

the widow Mendiluce an eminent place in the panorama of Argentinean and Hispanic

letters.

This is how she came to write the book. Edelmira read Edgar Allan

Poe’s essay “Philosophy of Furniture.” She was excited. She felt that she had

found a soul mate in Poe: their ideas about decoration coincided. She discussed

the subject at length with Carozzone and Atilio Franchetti. Following Poe’s

instructions to the letter, Franchetti painted a picture: an oblong room thirty

feet deep and twenty-five feet wide, with a door and two windows in the far

wall. He reproduced Poe’s furniture, wallpaper and curtains as exactly as

possible. Pictorial exactitude, however, was insufficient for Edelmira, so she

decided to have a replica of the room built in the garden of her ranch, in

accordance with the directions given by Poe. She sent her delegates (antique

dealers, cabinet makers, carpenters) hunting for the items described in the

essay. The desired but only partly attained result consisted of:

—Large windows reaching down to the floor, set in deep recesses.

—Windowpanes of crimson-tinted glass.

—More than usually massive rosewood framings.

—Inside the recesses, curtains of a thick silver tissue, adapted to

the shape of the window and hanging loosely in small volumes.

—Outside the recesses, curtains of an exceedingly rich crimson silk,

fringed with a deep network of gold, and lined with the same silver tissue used

for the exterior blind.

—The folds of the curtain fabric issuing from beneath a broad

entablature of rich giltwork, encircling the room at the junction of the ceiling

and walls.

—The drapery thrown open, or closed, by means of a thick rope of gold

loosely enveloping it, and resolving itself readily into a knot, no pins or

other such devices being apparent.

—The colors of the curtain and their fringe—the tints of crimson and

gold—appearing everywhere in profusion, and determining the

character

of the room.

—The carpet—of Saxony material—half an inch think, of the same crimson

ground, relieved simply by the appearance of a gold cord (like that festooning

the curtains) raised slightly above the surface of the ground, and thrown upon

it in such a manner as to form a succession of short irregular curves—one

occasionally overlaying the other.

—The walls prepared with a glossy paper of a silver gray tint, spotted

with small arabesque devices of a fainter hue of the prevalent crimson.

—Many paintings. Chiefly landscapes of an imaginative cast—such as the

fairy grottoes of Stanfield, or Chapman’s Lake of the Dismal Swamp—but also

three or four female heads, of an ethereal beauty—portraits in the manner of

Sully, each picture having a warm but dark tone.

—Not one of the paintings being of small size, since diminutive

paintings give that

spotty

look to a room, which is the blemish of so

many a fine work of Art overtouched.

—The frames broad but not deep, and richly carved, without being

dulled or filigreed.

—The paintings lying flat on the walls, not hanging off with

cords.

—One mirror, not very large and nearly circular in shape, hung so that

a reflection of a person in any of the ordinary sitting places of the room could

not be obtained from it.

—The only seats being two large, low sofas of rosewood and crimson,

gold-flowered silk, and two light conversation chairs, also of rosewood.

—A pianoforte made of the same wood, with no cover, and thrown

open.

—An octagonal table—also without cover—formed altogether of the

richest gold-threaded marble, placed near one of the sofas.

—A profusion of sweet and vivid flowers blooming in four large and

gorgeous Sèvres vases, set in each of the slightly rounded angles of the

room.

—A tall candelabrum, bearing a small antique lamp with highly perfumed

oil, standing beside one of the sofas (upon which slept Poe’s friend, the

possessor of this ideal room).

—Some light and graceful hanging shelves, with golden edges and

crimson silk cords with gold tassels, sustaining two or three hundred

magnificently bound books.

—Beyond these things, no furniture, except for an Argand lamp, with a

plain, crimson-tinted ground-glass shade, depending from the lofty vaulted

ceiling by a single slender gold chain and throwing a tranquil but magical

radiance over all.

The Argand lamp was not particularly difficult to procure. Nor were

the curtains, the carpet or the sofas. The wallpaper proved more problematic,

but the widow Mendiluce dealt directly with a manufacturer, providing a pattern

specially designed by Franchetti. Paintings by Stanfield or Chapman were not to

be had, but the painter and his friend Arturo Velasco, himself a promising young

artist, produced a number of works, which finally satisfied Edelmira’s desires.

The rosewood piano also posed a number of problems, all of which were eventually

solved.