Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight (23 page)

Read Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight Online

Authors: Jay Barbree

Tags: #Science, #Astronomy, #Biography & Autobiography, #Science & Technology

The Apollo team was overloaded with retired military—colonels and generals—doing little more than flying on North American’s travel vouchers to military reunions and such. Each was buying his stuff—each only accountable to self. And experience? Hell, they had none of that.

The whole thing smelled of military paybacks for aviation and aerospace contracts, and in the coming months while the review board investigated, while others were pointing fingers and protecting their own backsides, T. J. O’Malley put on his boots and began kicking ass and taking names.

North American’s most qualified and experienced aerospace engineers got busy redesigning and rebuilding Apollo to the specifications of the astronauts, and Neil Armstrong got busy learning how to fly one of the redesigned Apollo spacecraft. He knew Gus, Ed, and Roger’s deaths had given them the gift of time needed and by god, if Neil A. Armstrong was to have a say, they’d get it right for three fallen friends.

He also knew the crew selected to fly to the moon would be going on the backs of the

Apollo 1

astronauts and he managed a smile. “Thanks guys,” he spoke quietly. “We’ll get ’er done.”

* * *

Neil and the other astronauts hadn’t a clue that Russia’s cosmonauts were about to run into their own tragedy dogging their efforts to also reach the moon.

Less than three months after the

Apollo 1

fire, Cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov rode the first Soyuz spacecraft into Earth orbit. He had one comment: “Splendid.”

The Soviet Union’s senior cosmonaut judged their all-new spacecraft as promising and following a day of testing, the plan was for a second Soyuz to join him in orbit. The two spaceships would then dock and their two spacewalking pilots would switch spacecraft. The feat would put Russia’s cosmonauts back on par with America’s astronauts—a capability Russia needed to reach the moon. But no sooner had Komarov settled in while racing around Earth than the all-new Soyuz developed serious problems.

Unlike America’s Gemini and its future Apollo that ran on battery and fuel cell power, Soyuz was built to draw its energy from two solar panels.

The right panel extended.

The left panel did not. It remained closed. Nothing Komarov tried would release the solar wing.

By the second orbit, Russia’s mission control, located a few miles outside of Moscow, was on full alert.

Soyuz 1

was receiving barely half the electrical energy needed. Its systems and controls were failing.

Komarov’s shortwave radio transmitter died. His ultra-shortwave radio remained operational, but barely. He could only communicate with mission control sparingly and he received instructions to change the attitude of Soyuz’s face to the sun. The move could help pull in more power. It just might give him enough juice to free the jammed panel. It didn’t.

By the fifth orbit the new Soyuz began shredding itself and mission control feared for Komarov’s survival. His power was failing. Communications began to break up. He shut down the automatic stabilization system and went to manual control with his attitude thrusters.

The thrusters operated only in balky spurts. Komarov felt the ship getting away.

Controllers instructed the cosmonaut to let Soyuz go, let it drift. He would soon be moving through a series of orbits during which he would not be able to maintain voice contact with his flight controllers. Between the seventh and thirteenth orbits he would be away from tracking stations, out of touch.

This was the so-called daily “dead period” for Russian spacecraft and mission control instructed him to try to get some sleep. Then he moved out of radio range. He would be in a communications blackout for the next nine hours.

The time passed slowly. At the close of the thirteenth orbit they heard Komarov’s voice. His report sent chills through the control center. The ship was dead. Manual control with sputtering thrusters was sporadic at best. Soyuz was rapidly becoming a careening, wobbling killer with its pilot trapped inside.

Officials canceled the launch of the second Soyuz. They told Komarov they had to gamble to get him back to Earth. He would have to fire his retro-rockets for reentry on the seventeenth orbit and use all his strength and knowledge to try to manually hold Soyuz on a steady course. He would have to maintain attitude control through the fireball of reentry.

They didn’t have to tell Vladimir Komarov why.

The flight director said aloud what Komarov and everyone knew. “He is out of control. The spacecraft is going into tumbles that the pilot will have difficulty stopping. We must face the truth. He might not survive reentry.”

As a select few in NASA listened to a translation from America’s intelligence-gathering assets Neil Armstrong immediately recognized the cosmonaut’s problems. He and Dave Scott had faced much the same on

Gemini 8

.

In early 1958, a few months after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, President Dwight Eisenhower authorized the development of a top-priority reconnaissance satellite project operated by the CIA Directorate of Science and Technology with assistance from the U.S. Air Force. It was used to “eavesdrop,” and for photographic surveillance of the Soviet Union, China, and other areas from 1960 until May 1972. The project’s code name was Corona, but to hide its true purpose, it was given the cover name Discoverer and said to be a scientific research and technology development program.

In Russia’s mission control the flight director picked up his telephone and issued orders. A powerful car pulled up before a Russian apartment complex. Two men rushed into the building, emerging moments later with a woman. The car roared off toward the control center.

The woman was Valentina Komarov, the cosmonaut’s wife and the mother of their two children.

By the time she reached mission control,

Soyuz 1

was tumbling through space. Komarov had become ill from the violent motions several times. He forced calm into his voice when flight control told him he could talk privately with his wife.

They brought Valentina to a separate console and moved aside to assure her privacy. In those precious moments Vladimir Komarov bid his wife good-bye.

Soyuz 1

’s retro-rockets slowed his speed, but reentry began with Komarov having little control. He fought the spacecraft with his experience, skill, and courage. He judged his position by gyroscopes in the cabin. Incredibly, he aligned the ship correctly and held it firm until building atmospheric forces helped stabilize it.

First reports of the ship’s landing indicated it had touched down about forty miles east of Orsk. It seemed Komarov had accomplished the impossible, fighting his failed spacecraft all the way through reentry.

But the flight controllers had not witnessed what the farmers in the Orsk area saw as Soyuz fell to Earth. Though Komarov survived reentry, he was fighting his failed spacecraft spinning wildly all the way down.

The main parachute had not fully opened. His reserve chute fell away from his spacecraft, immediately twisting into a large, orange-and-white rag, trailing uselessly behind Soyuz.

At a speed of 400 miles per hour, cosmonaut Komarov’s spacecraft smashed into the earth. Its landing system included braking rockets fired normally just above the ground to cushion touchdown. But Soyuz slammed down hard and the rockets exploded, engulfing the spacecraft in flames. Farmers ran to the ship to throw dirt on the burning wreckage. An hour later they were able to dig through the smoldering ruins to find the remains of spaceflight’s latest hero, Vladimir Komarov.

The Russian space program, like its American counterpart, had experienced a stunning reversal and entered a period of reexamination. Russia as would the United States did not fly another spacecraft for 18 months.

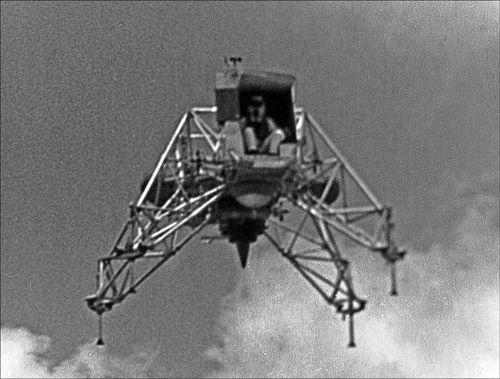

Neil Armstrong flying the LLTV. (NASA)

THIRTEEN

HOW TO LAND ON THE MOON

Following its launchpad fire Apollo would be grounded for 21 months, time needed to redesign and build new, safe flight hardware, time Neil knew the astronauts should be training to fly what was being rebuilt.

Planners came up with a free-flying mechanical contrivance that duplicated lunar gravity and flew much like experts anticipated the lunar module would. It was named the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle (LLTV), and Neil simply reasoned landing a spacecraft in the vacuum surrounding the moon required something altogether different from the skills used to fly winged vehicles in an atmosphere. Flying helicopters could not mimic the trajectories and sink rates of a lunar module and he felt the helicopter would be a waste of time.

The LLTV was a beastly looking contraption, an overgrown spiderlike vertical takeoff vehicle with four legs. It was immediately nicknamed the “Flying Bedstead.”

In its stomach was a 4,200-pound turbofan engine mounted on a gimbal, a device that allowed the engine’s thrust to swivel freely in all directions, keeping the LLTV balanced, which permitted its jet engine to be throttled down to support five-sixths of its weight to simulate the reduced gravity on the moon.

Why five-sixths? Because Apollo pilots would be landing on the moon in one-sixth the gravity of Earth, they had to know how the lunar module would fly in this low gravity, and to simulate these conditions, the LLTV had two hydrogen peroxide lift rockets with thrust that could be varied from 100 to 500 pounds. Sixteen smaller thrusters, mounted in pairs, gave the astronaut control in pitch, yaw, and roll, and for safety, there were six 500-pound-thrust backup rockets that could take over if the big turbofan engine failed, including one of the first zero-zero ejection seats.

So what is a zero-zero ejection seat? The two zeros refer to zero altitude at zero speed. The ejection unit can boost a pilot to safety from a vehicle sitting on the ground or from thousands of feet in the air. All of it was needed to train an astronaut to fly Apollo’s lunar module, and Neil was convinced that if you could build a trainer that would accurately duplicate all the landing conditions on the moon, you could train someone to touchdown safely on Earth’s nearest neighbor.

“Those smart Bell aero systems engineers did just that,” Neil said, adding, “The only thing they couldn’t do was rid the Earth from training in the wind because there is no wind on the moon.”

There were other questions but Neil thought the LLTV was just one dandy idea so after the

Apollo 1

fire, NASA’s prime Apollo contractors North American and Grumman got busy rebuilding and fireproofing the Apollo and lunar module while the ships’ likely moon-landing commanders Neil Armstrong, Pete Conrad, Jim Lovell, Alan Shepard, David Scott, John Young, and Gene Cernan busied themselves trying to master flying the Bedstead.

The skill necessary was the same eye-and-muscle coordination one needed to balance a dinner plate on a broomstick with one finger.

Then, on March 27, 1967, two months to the day after the

Apollo 1

crew died, Neil made his first and second test flights in the LLTV. But technical problems in the maiden Lunar Landing Training Vehicles grounded the first machines for the remainder of the year.

Early in 1968 improved versions were brought to nearby Ellington Air Force Base from Edwards High Speed Flight Station. Neil was first in line, and within a month his logbook recorded a total of ten training flights. Naturally he was asked if flying the Bedstead was becoming routine. “I wouldn’t call it routine,” Neil answered. “Nothing about flying the LLTV is routine. It’s not a forgiving machine.”

* * *

He continued his training flights and then shortly after lunch on May 6, 1968, Neil climbed aboard the lunar trainer and took his seat in the pilot’s box. This would be his twenty-first LLTV practice landing and he got comfortable. Technicians began the training procedure by connecting Neil’s necessary attachments.

It was one of those springtime Texas afternoons with lots of sun and puffy clouds, but this day there were also winds. Gusts were up to 30 knots, and Neil made a mental note. The winds could be tricky. Some of the Apollo astronauts disliked flying the demanding LLTV, but Neil felt differently. He knew if a pilot was going to land on the airless moon, he had to know how to do it before he arrived. He had little appetite for “learning on the job.”

Was he afraid? Not really. He simply believed in courage over timidity. He had an appetite for adventure over the love of doing nothing, but he certainly had respect for what could go wrong and he drove himself to the limits of being prepared. When he flew the unforgiving Bedstead or any other challenging machine, Neil consciously or unconsciously came back to the dream—the reoccurring dream from his adolescence where he was suspended in air. No aircraft. No wings. Only himself floating thousands of feet—even miles above in the sky—and as long as he held his breath, relaxed and kept his wits about him, he would not fall.

Strangely, he believed the dream to be real. It gave him confidence. Not a boastful confidence. Not arrogance. Again, a belief in his preparedness—in his acute awareness of how sharp and quick his flying skills had to be to pilot any nerve-racking unforgiving quirks of unproven craft. He simply prepared himself the best he could and lived the life of the test pilot.