Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight (19 page)

Read Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight Online

Authors: Jay Barbree

Tags: #Science, #Astronomy, #Biography & Autobiography, #Science & Technology

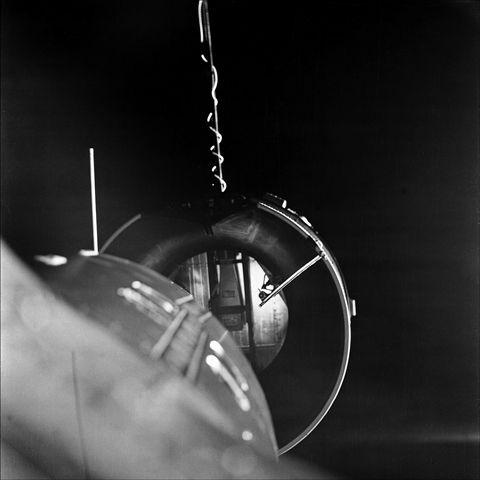

Gemini 8

aligned and ready for docking. (NASA)

“You couldn’t have the thrill down there we have up here,” Dave Scott told them, adding, “Just for your information, the Agena was very stable, and at the present we are having no noticeable oscillations at all.”

NASA commentator Paul Haney was back:

This is Gemini Control Houston here at 6 hours, 44 minutes into the flight. According to the best estimates that we have the actual docking took place at 6 hours, 34 minutes into the flight. We can verify this later through telemetry but that is the estimate of the flight director. The pilots still have about two hours work ahead of them before they will power down for the night and suspend their activities after this most busy and successful day. This is Gemini Control, Houston.

Neil Armstrong performs the first docking in space. (NASA)

Back on

Gemini 8

the crew and the docked ships moved out of radio contact with Mission Control. Ahead was one of the worldwide tracking network’s dead zones. No transmissions in. No transmissions out.

For the next twenty-one minutes

Gemini 8

and its Agena partner, forming a single, lengthy spacecraft of 44 feet, moved across the waters of the Indian Ocean and over the Bay of Bengal where something went wrong.

There was no way of telling anyone. It was Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott’s problem.

Suddenly, survival was job one.

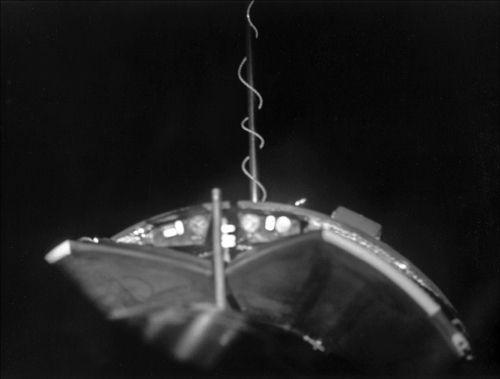

Mission Control Houston ready for the quiet, graveyard shift. (NASA)

ELEVEN

GEMINI 8

: THE EMERGENCY

It was quiet on NASA’s worldwide space-tracking network. Neil Armstrong and Dave Scott, with the successful first-ever docking of two spacecraft in their pockets, were winding down their day when Bill Anders walked into Mission Control. It was Anders’s first real assignment as an astronaut—relieving his veteran colleague Jim Lovell.

Anders had come aboard in NASA’s third group of astronauts. He had strategized by lobbying for CapCom; the experience would put him a step closer to a crew assignment. He hadn’t the slightest clue he would, in less than three years, join Jim Lovell and Frank Borman as one of three humans to first orbit the moon.

At the present,

Gemini 8

was out of radio contact somewhere over the other side of the world, and Lovell, the flight’s first-shift CapCom, told the rookie, “You should have an easy shift. The crew is getting ready to call it a night.”

Anders smiled as the tired veteran astronaut turned and walked away, leaving him to his debut as a space-crew babysitter.

He now stood alone before the CapCom console surveying the rows of flight controllers, each with a monitor, rising behind and above the others, each tier keeping a continuous watch on the crew and spacecraft. This efficient Mission Control operation was orchestrated by the flight director, the boss, on the CapCom’s right.

The freshman astronaut acknowledged Flight Director John Hodge with a glance and a smile. Hodge was also new. He was completing his first shift and his return smile seemed to say to Anders that he, too, would make it.

Hodge was about to be relieved by the more-experienced Gene Kranz, who in little more than three years would be the flight director in charge of Neil and Buzz Aldrin’s first landing on the moon. Kranz had dropped by to listen to the docking, and since Hodge had been at the flight director’s console for eleven hours, the two decided between themselves Kranz’s second shift of flight controllers should report for duty immediately.

Rookie Bill Anders and the second shift settled into their Mission Control seats. Many from the first team hung around to make sure no one had a problem moving into the flow.

* * *

Over China, the docked

Gemini 8

/Agena combination flew alone deep into the night. They had no ground stations to talk to and Neil readied the spacecraft for their first sleep period. Dave continued maneuvering the Agena with its attitude-control rockets. He turned the docked ships 90 degrees to the right. This yaw maneuver was one of several that had been scheduled to determine if Agena’s control system could relieve

Gemini 8

of some of its control duties. If it could it would save fuel. But this 90-degree turn took 5 seconds less than the full minute expected. This shorter maneuver prompted Dave to check his cockpit’s instruments. Something was wrong. Something was out of place. The Gemini/Agena’s stability was fraying noticeably. “Neil, we’re in a bank,” he said. “I have a 30-degree roll on my 8-ball.”

The 8-ball instrument on a pilot’s cockpit panel is an instrument of crosshairs showing a flyer an artificial horizon and the spacecraft’s degree of tilt to the left or right “bank.” It gets its name from the eight ball in the game of pool. It is held in place by a fast-spinning gyro, a device that holds an object fixed in place, and if the gyro fails, the 8-ball will tumble—no longer giving a pilot an artificial horizon and an indication of the spacecraft’s bank. Armstrong quickly thought Scott’s 8-ball had tumbled, but when he checked his own they were identical. His 8-ball showed them rolling and he made some efforts to reduce the bank angle by triggering short bursts on the Gemini’s maneuvering thrusters.

At first it seemed Neil was successful. Both pilots were convinced their target rocket was the culprit because they could easily hear the Gemini thrusters when they fired. They were on the Gemini’s nose and behind them and every time they would fire Neil would later say, “It was like a popgun—

crack, crack, crack

—and we weren’t hearing anything, not realizing until later that the thrusters only popped when they ignited. As long as they were burning they were silent.”

What Neil and Dave hadn’t known was that if a thruster was burning continuously, they wouldn’t be able to hear it. So they waited for four minutes. There was “no joy.”

The roll began again, only faster, and Neil asked Dave to shut off all of Agena’s controls.

Dave had the control panel for Agena on his side but he had little success. He sent command after command, jiggled switches, recycled them and the roll kept increasing and Neil became concerned that the stress and strain of the violent rolling might break apart the linked spacecraft, possibly igniting the Agena’s 4,000 pounds of fuel. That’s just what he needed: a fireball above China. Mao Tse-tung, the chairman of China’s communist party, would go berserk. Neil would have to use

Gemini 8

’s maneuvering thrusters to undock, to back away from the Agena, but that could rip the whole damn thing apart and shower their orbit with little pieces and … And God could let the Sun fall from the sky! Instantly it was clear. He had one choice. If Agena’s fuel didn’t blow, they would soon pass out from the centrifugal force of the increasing spin and if they were going to die anyway, he reasoned, screw it. Let’s take our best shot.

“We’re going to disengage,” Neil told Dave who immediately agreed, and suddenly Neil’s hands were magic. He was firing bursts from the Gemini’s maneuvering thrusters and he fought and fought until Scott was convinced Neil had steadied the linked spacecraft enough to undock and Dave yelled, “Go,” and he hit the undocking button as Neil gave the thrusters a long hard burst.

“Come on,” Armstrong shouted, and there immediately came a bang from the motors driving the docking latches open and the docked ships freed themselves with

Gemini 8

pulling straight back. It was like two people facing one another and each using their hands to push the other away. For every action there’s an opposite reaction, Neil knew, which dampened his concern over the distance between them and the Agena. With no resistance in space,

Gemini 8

and its target rocket should continue moving apart in their separate orbits and …

Neil fires his thrusters to disengage from Agena. (NASA)

What’s this?

Gemini 8

was beginning to spin faster. Instantly the astronauts realized the problem was not in the Agena, it was in

Gemini 8

. It was now increasing its spin, making them even more dizzy, and Neil Armstrong’s analytical mind stepped up to the plate. Despite the growing chaos, he was quick to realize his spacecraft’s spinning was a disaster in the making.

Gemini 8

was an out-of-control dilemma that would keep growing until the centrifugal forces ripped everything apart and he and Dave would not only lose their focus, they would lose their vision and their consciousness.

To stabilize his spacecraft

Gemini 8

’s commander recognized he needed an independent control system. One stronger than his attitude-control thrusters, and that could only be

Gemini 8

’s RCS (Reentry Control System).

The RCS had two individual rings of hypergolic rockets. They were more powerful than the ship’s troublesome attitude-control thrusters, but they were a separate part of the spacecraft for one reason. A fresh, independent control system was a must to position

Gemini 8

correctly for its return to Earth. Without it, Neil and Dave would simply not get home. They would burn up during an out-of-control reentry.

The book says that once you activate your two RCS rings, A and B, you must then land at the first opportunity.

But Neil also knew they had only one real hope. Use

Gemini 8

’s primary reentry control rockets.

He was thinking again that he and Dave were going to die anyway so what the hell, with their chances being slim to none, he’d take slim every time.

Both astronauts wavered on the edge of losing consciousness and when they first tried to fire their reentry thrusters nothing happened. After turning the system off, then trying again, the thrusters responded, and Neil was busy trying to stabilize

Gemini 8

when they came in contact with the tracking ship

Coastal Sentry Quebec

.

James Fucci, the CapCom aboard, was fussing because he couldn’t get a solid signal, unaware that the spacecraft was rolling.

“

Gemini 8

, CSQ CapCom,” Fucci called. “Com check. How do you read?”