Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight (8 page)

Read Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight Online

Authors: Jay Barbree

Tags: #Science, #Astronomy, #Biography & Autobiography, #Science & Technology

America’s first in space rocketed to a height of 116 miles and flew some 300 miles across the Atlantic before a huge parachute dropped his spacecraft into the sea and recovery forces plucked Alan Shepard and

Freedom 7

from the waves.

America still hadn’t reached orbit as Yuri Gagarin had, but the U.S. was in space. Neil applauded. He had a decision to make.

FOUR

THE MOON IS CALLING

Alan Shepard’s successful suborbital spaceflight had settled questions for President John Kennedy who accepted that Russian rockets and spacecraft were bigger. But he was coming to realize the Soviets weren’t better because their technology could only build large nuclear warheads. They needed monstrous missiles to carry their monstrous bombs, but not America. With the significant breakthrough in size reduction in America’s hydrogen bomb warheads, the same bang could be carried to any target by a rocket a third of the size. For this reason President Kennedy was convinced we were actually ahead of the Russians in rocketry, space vehicles, and the digital computer. He felt confident that in any technological race we could beat them. And Kennedy was ready to take what many considered a huge gamble.

Neil was in Seattle working on the Dyna-Soar project that day in May the president addressed Congress:

I believe this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before the decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space, and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.

There it was. Kennedy had thrown down the gauntlet of know-how and challenged the Russians. Congress leapt to its feet. Its members’ applause shook the walls of the Capitol, and Neil Armstrong instantly felt the call. Kennedy wasn’t just talking about astronauts orbiting Earth, he was talking about going somewhere humans had never been. He was talking about Columbus sailing to the New World, Lewis and Clark carving a trail to the Pacific Northwest, Byrd reaching for the North Pole. He was talking about exploration—stacking more wood on the stockpile of knowledge—and Neil instantly knew he would like to be a part of that challenge. But once again he was in the wrong place. Flying the X-15 to an altitude of 60 miles wouldn’t get the job done. He had to become an astronaut. Quietly and instantaneously he moved to join the Mercury Seven as the launch team on the Redstone pad renewed its efforts to keep moving.

Gus Grissom’s

Liberty Bell 7

Mercury spacecraft was ready to fly. On July 21, 1961, the second American lifted off and flew an almost exact duplication flight of the first. The splashdown was perfect, but that’s where the duplication ended.

Gus was going through the drill of readying his capsule for recovery when an explosion blasted away his hatch.

Grissom’s hatch had been modified to use an explosive primer cord instead of the mechanical locks on Alan Shepard’s capsule. The primer cord inexplicably fired, and Gus saw waves coming into

Liberty Bell 7.

He scrambled out—swam for his life as frogmen tried to save his capsule. They failed but got Gus safely aboard the helicopter. Right away the experts began trying to determine the cause of the detonation. Some were sure the design of the capsule made an accidental explosion impossible. They insisted Grissom had to have hit the emergency plunger, which blew the hatch. “The hell I did,” Gus snorted. “The damn thing just blew.” The astronauts backed him all the way, and an accident review board cleared Gus of any wrongdoing. Four decades would pass before

Liberty Bell 7

would be brought up from the ocean floor.

Gus was right.

* * *

Sixteen days after Gus Grissom’s flight Major Gherman S. Titov, who had backed up Yuri Gagarin, was sent into orbit. He stayed a full day.

Washington and NASA could only shake their heads.

It was obvious there was no longer a need to fly more Redstone suborbital flights. If America was going to reach orbit the same year as the Soviets and set foot on the moon by the end of the decade, they needed a bigger rocket to carry the Mercury spacecraft. It was time to bring Atlas to the launchpad.

The Atlas worked well boosting nuclear warheads 5,000 miles. But it was another story when it came to hauling astronauts. Atlas had no internal structure. Its strength was from inflation, much like a football. But its thin skin would collapse under the heavy burden of a Mercury spacecraft, much heavier than a nuclear warhead. It needed lots of fixing.

“Put a belt around its waist and it won’t collapse,” said famed rocket engineer John Yardley. Which they did: The steel belt held for chimpanzee Enos’s orbital flight and they moved John Glenn’s Mercury-Atlas to the launchpad while NASA went hunting for more astronauts.

With President Kennedy’s challenge to reach the moon before the end of the decade the agency needed pilots to fly the Gemini and Apollo spacecraft. The Mercury Seven simply couldn’t do the job alone.

The next group to be selected would be made up of nine astronauts. Like the Mercury Seven named for their spacecraft, the new group would be called the Gemini Nine.

Neil reached for an application, but as fate would have it, his small family was fighting a greater battle.

His infant daughter Karen Anne, who he’d doted over and nicknamed Muffie, was fighting an inoperable brain tumor. Neil and Janet had tried every specialist, had Karen Anne in every available medical facility, sought treatment and hopefully a solution from every corner of the medical world.

Neil’s analytical and scientifically driven core would not permit him to believe there could not be a procedure to surgically remove the tumor. He searched everywhere, but as Christmas 1961 approached Karen Anne was becoming weaker. Neil and Janet got busy making their daughter’s third Christmas special.

They did, and even though Karen Anne could no longer fully stand, she enjoyed her third holiday season.

Neil and Janet refused to abandon their search to make her well. Despite their unrelenting hunt for what would save her, their devoted efforts could not keep tragedy away from their door.

On Sunday morning January 28, 1962, Janet and Neil’s sixth wedding anniversary, Karen Anne died. She succumbed to pneumonia and other complications brought on by the tumor.

The Armstrongs were devastated. Janet’s emotions were uncontrollable. Neil’s grief was a self-imposed quiet. Four-year-old brother Ricky was trying to understand. Friends and family gathered to comfort and help. They buried Karen Anne in the children’s sanctuary at Joshua Memorial Park in Lancaster, California. A poem rested among the flowers: “God’s garden has need of a little flower; it had grown for a time here below. But in tender love He took it above, in more favorable clime to grow.”

The small stone marking her grave read: “Karen Anne Armstrong, 1959–1962.” Between the two lines was carved, “Muffie.”

NASA’s High Speed Flight Research Center grounded all test flights the day Karen Anne was laid to rest.

Very seldom was Neil Armstrong not in control of his emotions. He would long for his daughter for years—no, for the rest of his life. He would never lose those special protective feelings he had for his little girl. Again and again he relived his inability to find the science, to develop it, to learn how he could have helped Karen Anne. In a large sense it came close to wrecking the man—a man who lived within the precise control of his abilities and limitations.

From the day Karen Anne was buried he could never pass Joshua Memorial Park without stopping, without visiting her grave. And yet in time Neil would come to accept the fact that science simply wasn’t there when he needed it. No one on January 28, 1962, knew how to rid a body of an inoperable brain tumor. He didn’t like it, but Neil reached a place where he could live with the fact that there wasn’t anything more he could have done to save his little girl.

Eight years later during Neil and the

Apollo 11

crew’s postflight visit to London, a two-year-old girl who came to see the spacemen was nearly crushed against a barrier by the adoring throng. Neil went to her rescue, then gave her a kiss. He clutched her safely until she could be returned to her mother.

The crowd of more than 300 cheered that moving moment. The next morning a London newspaper carried the headline, “2-Year-Old Girl Bussed by Moon Man.”

Neil seldom spoke of this overwhelming heartache in his life. But others close to him were convinced Karen Anne’s death was the single most important reason he would submit his name to become an astronaut. Her death gave him a new purpose. A few months before Neil’s own passing I asked him, “Is there something of Muffie’s on the moon?”

I read his smile to mean yes.

* * *

Only 23 days following his daughter’s death the sun was coming into view at 6:47

A.M.

at the Armstrongs’ cabin in California. Three thousand miles to the east it was 9:47

A.M.

—the sun was already shining brightly.

John Glenn sat atop his Mercury-Atlas ready to become the first American to rocket into orbit. Neil Armstrong sat before a television set. With the recent passing of his daughter he found it difficult to think about anything else. He had no way of knowing he was about to watch one of his future best friends soar into history.

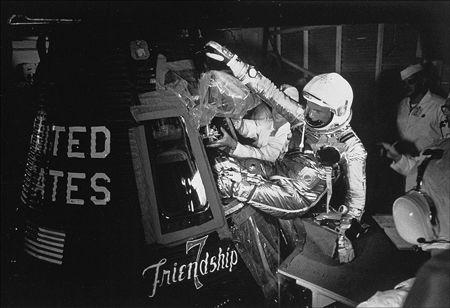

John Glenn boards

Friendship 7

. (NASA)

“Godspeed, John Glenn!” the voice of astronaut Scott Carpenter boomed from the television. Neil leaned forward.

“Five, four, three, two, one, zero!”

Voices everywhere fell silent.

John Glenn’s rocket was ablaze.

“Roger, the clock is operating,” the marine reported to Mercury Control, “We’re under way.”

The sunlit Atlas-Mercury climbed from Cape Canaveral’s famous rocket row as Neil focused on the spacecraft Glenn had named

Friendship 7

. It rested atop the flaming rocket and he could see the gimbals on the booster’s main engines working in concert with the vernier rockets. He heard John say, “We’re programming in roll okay.”

Glenn quickly settled into his climb and just as quickly he and

Friendship 7

flew into Max-Q. Pressure squeezed his Atlas. The steel belt around his rocket’s girth held. The marine fighter pilot reported, “It’s a little bumpy along here.”

He flew on into space. He was feeling what had been felt by Gagarin, Shepard, Grissom, and Titov. He now wallowed in weightlessness. He told Mercury Control, “Roger, zero G and I feel fine. Capsule is turning around. Oh”—Glenn shouted—“that view is tremendous!”

Glenn’s Atlas-Mercury heads for orbit. (NASA)

America was in orbit and John Glenn settled in for three planned trips around Earth.

He knew the taxpayers who had sent him there wanted desperately to know what he was seeing.

Only minutes after reaching orbit he was witnessing his first sunset. He issued a glowing report. “The moment of twilight is simply beautiful,” he told the millions listening. “The sky in space is very black with a thin band of blue along the horizon.”

His eyes became acclimated to the universal darkness, and he turned down his cockpit’s lights. He was now moving through the unbelievable black velvet, seeing so many firsts: a defined blanket of the brightest, most clearly defined residents of the universe; glorious stars, billions and billions of them; swirling galaxies, constellations, quasars, nebulae with their luminous, dark clouds and sprinkles of dust. And there were the planets, bold in the blackest of black skies. He could only stare in wonder at his first run through Earth’s night side.