Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight (5 page)

Read Neil Armstrong: A Life of Flight Online

Authors: Jay Barbree

Tags: #Science, #Astronomy, #Biography & Autobiography, #Science & Technology

No science aboard this one. It was a satellite to simply demonstrate such a device could successfully be placed in Earth orbit, and he fitted it within a pointed metal nose cone and watched technicians installing it atop the R-7 booster.

Once the rocket’s technological glitches had been resolved, events moved rapidly and they left the launchpad for safety behind thick concrete walls. The final countdown went quickly, heard only by the launch team, a handful of experts, and those officials protecting their place in the Soviet hierarchy.

An unsuspecting world was about to be shocked. The huge launch tower and its work stands were rolled back. The last power umbilicals between the tower and rocket separated, falling and writhing into their places of rest.

The rocket now stood alone.

The minutes were gone.

The final seconds were passing. Korolev’s voice rang out:

“Zashiganiye! Tri, Dva, Odin.”

Enormous flame created a pillow of fire. It lashed and ripped into curving steel, followed concrete channels blowing long unbroken bright-orange flames across the desolate landscape. A continuing thundering roar followed. It rolled over Baikonur as Korolev’s rocket climbed on an unbroken column of fire, delighting all that watched before leaving them and speeding away to reach for where nothing created by man had ever been. Korolev stayed inside. The Russian scientist was far more interested in the readouts from his rocket than seeing the startling, pyrotechnic display R-7 had created. He was not disappointed. The numbers were perfect. Engines cut off on schedule. Stages separated as planned. Then, when the last engine died, protective metal flew away from the satellite. Springs pushed it free in space.

The satellite became known as Sputnik (fellow traveler). Obeying the laws of celestial mechanics, it immediately began to fall, beckoned invisibly toward the center of Earth. As fast as it fell in its wide, swooping arc, the surface of the planet below curved away beneath the falling satellite moving at a speed of 18,000 miles per hour in its orbit around Earth.

Some hour-and-a-half later it came back. Accounting for the movement of Earth beneath its orbital track in the time it took to circle the globe, Sputnik’s path now took it fifteen hundred miles north of its still-steaming launchpad. It swept across Asia transmitting its incessant lusty

beep.

The loudspeakers of Baikonur blared its voice. Its launch team broke into cheers and shouts of joy. Korolev turned to them and spoke with deep feeling, “Today, the dreams of the best sons of mankind have come true. The assault on space has begun.”

* * *

Neil Armstrong was in nearby Los Angeles at a symposium held by the Society of Experimental Test Pilots when Sputnik reached orbit.

He was disappointed Sputnik didn’t belong to America, but found the Russian launch encouraging. “It changed the world,” Neil said. “It absolutely changed our country’s view of what was happening, the potential of space. I’m not sure how many people realized at that point just where this would lead.

“President Eisenhower was saying, ‘What’s the worry? It’s just one small ball.’ But I’m sure that was a facade behind which he had substantial concerns,” Neil explained. “Because if they could put something into orbit, they could put a nuclear weapon on a target in the United States. The navigation requirements,” he added, “were quite similar.”

That said, in Neil’s judgment the Soviet Union was without question technologically inferior. Someone had dropped the ball and it gnawed at him. He knew that Dr. Wernher von Braun and his Huntsville, Alabama, group were better. He knew von Braun’s seasoned engineers had built rockets that were already reaching space, and America could have been in orbit with one of von Braun’s Redstone rockets and a couple of upper stages long before now. Why weren’t they? Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson.

Neil, as did many at the High Speed Flight Station knew Wernher and his group had been trying to get official approval to punch a satellite into Earth orbit for more than a year. But Wilson thought it was just so much nonsense and he and President Eisenhower were perfectly willing to put America’s prestige on a larger version of the Navy’s Viking RTV-N-12A sounding rocket. The Navy had tested about ten. About half had failed and the final launcher to carry a satellite was to have a larger engine and additional upper stages. In a sense the United States was putting its reputation on a yet-to-be built paper rocket named Vanguard.

Eisenhower and Wilson undressed it from its Navy whites and hung a sign around its neck that read “Civilian.” It was now part of an international science project, the IGY (International Geophysical Year), which had a membership of sixty-seven nations. No one was sure the pencil-shaped thing would fly but it was the politically correct thing to do.

In 1956, Wilson ordered von Braun to remove Redstone 29 from its launchpad. It could have been a year ahead of the Russians in launching a satellite. But it wasn’t. Neil and others on the front line of research wanted to go to Washington and ride Wilson out of town on a rail. Instead Neil went outside with the others from the test pilots’ group to look for what was now orbiting Earth.

According to some, Sputnik could be seen sweeping over an early evening Los Angeles, but Neil knew better. There was too much reflected light in the metropolis’s night sky for that. It might be possible to see the large trailing rocket stage glinting from the sun that was still lighting it above Earth’s early darkness. The conditions would have to be just right. Neil and others looked for a while but, as he had expected, there simply was too much reflected glow. They gave up and went back inside.

* * *

Only a month after

Sputnik 1

, the Russians did it again.

Sputnik 2

raced more than a thousand miles above Earth. On board was a living, breathing animal. A dog named Laika.

Americans were livid. Was Eisenhower fiddling while Rome burned? Where were our rockets? Where were our satellites? What the hell was going on? The president got the message. He acted, but prematurely. A civilian launch team working on Vanguard rushed the unproven rocket to its launchpad. On top was a grapefruit-size satellite that was so small it weighed only a laughable three pounds.

The day was December 6, 1957. The launch team neared the end of its countdown and an anxious hush fell over a hopeful America.

“T-minus five, four, three, two, one, zero.”

The slender Vanguard ignited, covered its pad with flaming thrust, and rose four feet, no more, before crumbling into its self-made fireball, consuming not only itself, but burning most of its launch facilities, leaving only blackened steel and ash.

The slender Vanguard ignited and rose four feet before consuming itself in its self-made fireball. (U.S. Navy and Air Force)

The loss of Vanguard wounded our pride, again. It also came close to destroying our confidence, and most Americans knew it was time for something to be done. The Russians were kicking us where we sat and it was time for a stubborn White House to call in the cavalry—to call in the von Braun team.

Eisenhower did, and Redstone 29 was hauled out of storage and refitted. A thirty-one-pound radiation-measuring satellite was mounted atop the rocket stack called Jupiter-C. The president and his White House didn’t want to be reminded that the rocket was the same rocket that could have placed a satellite in orbit ahead of Sputnik. So the order came down to change the name and lessen their shame. The rocket would no longer be called Jupiter-C. It would now be called Juno-1.

On January 31, 1958, at 10:45

P.M.

eastern the launch button was pushed. After waiting more than a year to fly, Redstone 29 came to life.

* * *

Yellow flame and thrust splashed outward in all directions. A huge pillow of dazzling fire gushed forth and thunder crashed across the Cape.

Those lucky enough to be there blinked at the searing flames and bathed in that marvelous roar. They cheered and screamed and some cried as the Juno-1 burned a fiery path into the night sky, reaching for von Braun’s stars. One hundred and six minutes later, its satellite

Explorer 1

returned from the other side of Earth. America was in orbit.

A grateful and jubilant nation was at von Braun’s feet.

Huntsville, Alabama, rocked with a wild and furious celebration. Horns blared and cheering thousands danced and hugged each other in the streets. Former defense secretary Charles E. Wilson, who had single-handedly stopped von Braun’s efforts to reach Earth orbit, was hanged in effigy. Neil Armstrong was gratified. He was most happy von Braun’s Huntsville group had proven America was and had been ready. He had a glimpse of the future. Perhaps pilots would not just be riding rocket planes across the skies. With the success of Sputnik and Explorer, pilots might soon be at the controls of spacecraft in orbit.

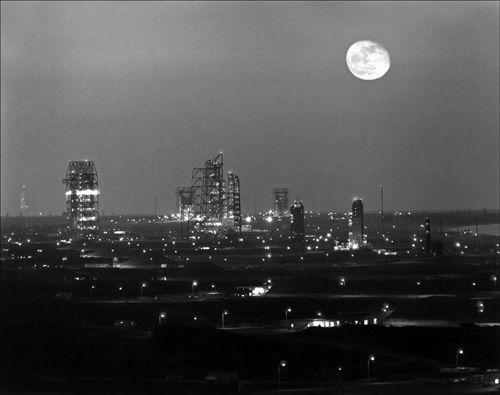

Cape Canaveral’s sprawling rocket launch complex under a 1958 moon. (U.S. Air Force)

THREE

THOSE WHO WOULD RIDE ROCKETS

Come the fall of 1958 Neil was surprised to see the new congressionally formed National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s recruiters swarming about in search of astronauts for a new man-in-space project called Mercury.

One of Neil’s assigned projects was the Dyna-Soar, a space plane he did not know then would become the forerunner of the space shuttle. It was a plausible idea, and to fly it, that project had earlier recruited astronauts. Nine were selected on June 25, 1958, for the Man-In-Space-Soonest (MISS) group.

“I was in the first lineup,” Neil said, but with the formation of NASA, the Dyna-Soar astronauts were short-lived. The new space agency was starting all over and in October 1958 it set about recruiting the Mercury Seven astronauts.

Most who wished to apply hurried to Cape Canaveral, the place in those days considered vital, intensely exciting. It was in fact Florida’s new dream attraction for tourists.

At night it was an all light show. Blinding searchlights surrounded its launchpads and blockhouses with their towering, shining rocket gantries. Support structures and hangars, even office buildings, were also awash with multicolored illuminations and soon it was obvious the bright lights were attracting the daredevils and the foolish.

But NASA rejected them outright, sending home the race-car drivers and mountain climbers along with all others from outside the pioneering family of aeronautics. The new space agency wanted the Neil Armstrongs, the John Glenns, the Alan Shepards—stable, college-educated test pilots screened for mental difficulties—not anyone willing to step outside of present-day accepted flight norms.

It was also unspoken that NASA did not want just experience. The agency did not want those getting on in years. This left out famed Air Force test pilot Chuck Yeager, who had had his day in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Yeager broke the sound barrier October 14, 1947. What these new astronaut recruiters wanted more than a decade later was really NASA’s own research test pilots like Neil and Scott Crossfield. These NASA pilots were flying all sorts of cutting-edge machines including the X-15, a rocket plane capable of reaching space. They were considered head and shoulders above their military counterparts by those who knew.

Unofficially Neil was asked to apply for Mercury. He found the invitation tempting, but he passed. He liked combining his engineering talent with test flights that had wings, and the X-15 had wings—not big wings, but wings, and even reporters were coming around calling it America’s first spaceship.

The X-15 was really the most evil-looking beast ever put in the air. It was a 15,000-pound black horizontal rocket with little fins. It had a large blocky tail. Its black paint was there to absorb extreme heat generated by speed-induced friction in denser atmosphere. And best of all you could fly it—not into Earth orbit, yet, but that would come later with bigger rocket planes with heat shields. Neil simply could not warm to the idea of being strapped inside a capsule, a spacecraft like the proposed Mercury. It had no controls, no wings, no way to get you out of trouble bolted to the top of something trying to explode. But this was what NASA was building. A capsule you couldn’t fly … but, oh, they

were

planning an escape tower with an instant rocket to snatch you away from a failing booster. Chuck Yeager had a name for those who would ride in it, “Spam in a can.”