Neverland (12 page)

Authors: Douglas Clegg

Books such as this one fed our imaginations.

In Neverland I sat on the edge of a rusted-out old wheelbarrow and thumbed through the

Playboys

. Sumter had gone through and sketched moustaches or broken teeth onto the girls’ faces. Their breasts thrust out of the photos like grocery bags, their hair thatches were like hedges that needed trimming, their skin was soft and smooth. None of these girls looked like she had anything to do in life but be beautiful and still and waiting.

Playboys

. Sumter had gone through and sketched moustaches or broken teeth onto the girls’ faces. Their breasts thrust out of the photos like grocery bags, their hair thatches were like hedges that needed trimming, their skin was soft and smooth. None of these girls looked like she had anything to do in life but be beautiful and still and waiting.

“Turn-offs: Insensitive people, people who don’t like animals,” he said in a high falsetto. “Turn-ons: People who like to have fun, people who love life in all its variety. Look at the bush on

that

one.” He jabbed his finger over my shoulder into the pubic area of Miss June.

that

one.” He jabbed his finger over my shoulder into the pubic area of Miss June.

I slammed the magazine shut. “This is boring, I thought you had to do something.”

“I do. But it’s kind of a ritual, and maybe you shouldn’t be here to see it. Maybe you’re too young. Maybe it’ll give you

nightmares

.”

nightmares

.”

“I’m older than you.”

“Emotionally immature, that’s what Mama calls you. She says you’re a hypochondriac and a neurotic and your mama and daddy are at the root of your problem.”

“Your mama sucks.”

“Is she wrong, Beau? Hmm? Is she? You and your circulation problems? They only come on when you can get the most attention. Do you think there’s a connection? Hmm?”

I will admit that I wanted to hit him for saying this, and I wanted to cry, but I never cried. It was just one of those things I never did. Hit him, yes. That urge was harder to keep down.

“It’s no big deal, cuz, honest, and the only reason I know is because, you know, the god Lucy told me it, and Lucy says you can be healed and saved and cured and all that. But only if you believe in Lucy.”

“If Neverland’s all around us, why can’t I see it more?”

“If it’s what you really, really want, but it gets scary. You sure you want to see?”

At that moment I almost said no. That small voice of conscience that my mother always talked about—that ghost of a voice in the back of my head—almost warned me away from this shack, this blood relation, this god of his.

But I said, “You bet.”

“If you really see Neverland, Beau, you will never be the same. You’ve already seen the face of god, and now you want to see the All.

You will never be the same

. You hear?”

You will never be the same

. You hear?”

I shrugged.

“Feed it. In the crate.” He held up a small safety pin, its sharp point gleaming. “Pray for what you want, and feed it.”

Sumter led me back to the crate, lifting the lid. “Now open your mouth and close your eyes, and you will get a big surprise.”

“I’m sure,” I said between clenched teeth. I almost did not want to look.

“Close your eyes,” he said softly. “And pray. You want to see the All, don’t you?”

“Uh-uh.”

“Close your

eyes,

Beau, and pray to see.”

His voice was like a rusty nail poked into my forehead, and for an instant I shut my eyes. I felt something tap at the back of my hand, almost tickling me, and then the sharpness of a pin.

Feed it

.

eyes,

Beau, and pray to see.”

His voice was like a rusty nail poked into my forehead, and for an instant I shut my eyes. I felt something tap at the back of my hand, almost tickling me, and then the sharpness of a pin.

Feed it

.

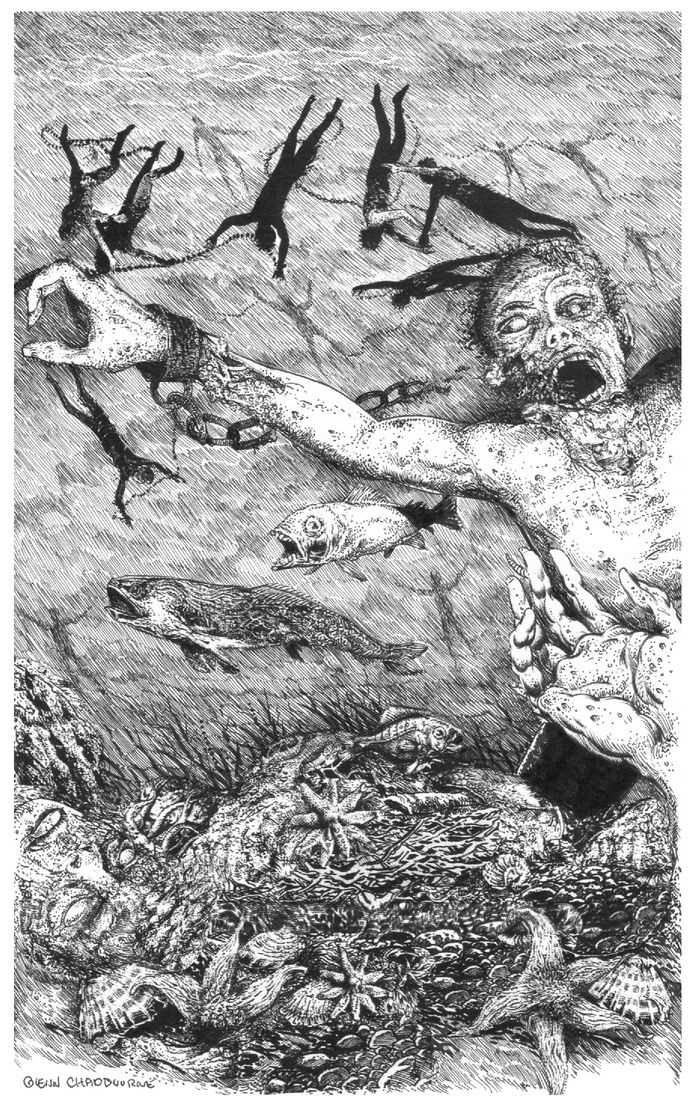

“Jeez,” I gasped, opening my eyes to see a small dot of blood drop into the crate. Something like a chicken foot reached out from the crate and grabbed my left hand by the wrist. Its scaly talons pressed sharply into my skin and tugged me toward the opening, into the crate itself, and the wind was knocked out of me. I felt myself falling down a vast endless shaft, the way you fall in a dream, with no ground to come down to. Brilliant tongues of fire shot out all around me, turning to deep blue waves passing over my head. I saw what looked like a woman’s face, screaming, only the skin had been eaten at, as if by fish. It was bloated and gray and chewed, but still

the mouth was open and the sound that came out was like a child crying out without knowing words.

the mouth was open and the sound that came out was like a child crying out without knowing words.

I was then on land, standing just outside the shack. All around me were colors I had never seen before, colors that I don’t even have names for, colors that made me angry and worried, exploding around me like bombs. My stomach was queasy, my heart beat irregularly and slowly, my mouth tasted of dirt and mold. In the distance were figures dancing on a hillside, and there were cacophonous shrieks as if some tone-deaf person were singing in a language I could not make out. The sky was fragmented into sharp angles and octagonal clouds, and the entire universe’s geometry had somehow expanded outward into shapes like strings of rock candy. Trees swayed in a strong wind, bending toward me, whispering; seagulls flew in great flocks with fish between their jaws, fish that screamed for release; the damp earth slithered and curled around my toes, its nightcrawlers and millipedes and pale white grubs chewing, chewing, chewing—as if they were inside my brain chewing on it. Somewhere among the trees something walked—I could only see its shadow, for the trees hid it well as they murmured their warnings to me.

Something walked there on all fours.

The sound of the trees became the sound of children laughing.

What walked there behind the thin line of trees, lit by the colors of madness, was not man or woman or animal.

And I knew that it was coming for me, with its hooves and claws and fingers and teeth—coming for me to do what only the savage god could do.

Feed.

I tried to scream, but had no voice.

I tried to scream because I did not want to be alive, because being alive hurt, because being alive meant

god would feed on my flesh.

god would feed on my flesh.

I heard Sumter’s voice in my head whisper, louder than the chewing sounds, louder than the discordant voices: “The All. It’s the All. Our father who is the All.”

FIVE

Playmates

1I opened my eyes not more than a second later, and I was lying in the lumpy earth of the shack, and Sumter stood over me laughing. “Fooled you, Beau, fooled

you

.” Then, hearing a noise, he turned toward one of the filthy windows and said, “Dang, here come the island geeks.”

you

.” Then, hearing a noise, he turned toward one of the filthy windows and said, “Dang, here come the island geeks.”

I felt like I had gotten caught in some undertow and had almost drowned. I blinked several times to make sure that whatever I had just imagined I’d seen was definitely not there. I sat up. “What the hell,” I gasped. I felt the earth spinning around me and wondered if I would be sick. I felt some kind of pressure beneath the skin at the base of my skull, like something pushing down hard from beneath the bone, trying to get out. When Uncle Ralph had his hangovers, he moaned about his head feeling like it would split, and this is what it felt like, but a hangover without ever having had a drink. “What was

that

?” I asked. I looked back at the crate, but it was just that, a crate. I thought for a second that I heard something scuttling around inside it, but it could’ve been my imagination. I thought I heard something

breathing

inside that crate. “What you got in there?”

that

?” I asked. I looked back at the crate, but it was just that, a crate. I thought for a second that I heard something scuttling around inside it, but it could’ve been my imagination. I thought I heard something

breathing

inside that crate. “What you got in there?”

But Sumter didn’t pay me any mind. “Shh, Beau, I think we got

spies

outside.” His attention was completely on the window.

spies

outside.” His attention was completely on the window.

I glanced up to it and saw faces pressed up against the glass: A girl and two boys were peering in.

THERE was one other group native to the peninsula besides the Gullahs. They were known as white trash, and they were almost a tribe. Gullahs were somewhat respected, even if in a condescending way. They tended to be employed and were more often than not smarter than the tourists. But the white trash were another story. They were drunk and raucous and filthy and just bad to know. To those of us from off-island, anyone who could be comfortably slotted as white trash were, in effect, of the lowest caste and untouchable. It was the meanest thing you could call anyone in the South, and on Gull Island they were like dirt beneath fingernails, people to feel superior to. The only group Grammy Weenie despised more than white trash were carpetbaggers, although I do believe that she might insist that these groups were one and the same.

These three kids peering at us through the window were definitely white trash. Grammy Weenie always said, “Don’t you get involved with those white trash, just let them crawl back under the rocks from which they came.”

Sumter went up to the window and growled at the white trash kids. “We shoot spies at dawn,” he said, flipping the bird at them.

But the girl licked the dirty window, sponging her tongue in a snail trail across the pane. One of the boys ran around to the door to Neverland and pushed it boldly open, waiting for his companions before he would take a step in.

2The girl’s name was Zinnia, she told us in her almost unintelligible drawl, and she stepped through the door to Neverland as if she owned the place.

Her hair was lemon-juiced dirty blond, and she kept scratching at a place just above her forehead where her bangs curled down almost to her eyebrows. “Named for the flower, ’cause my ma tells me that I grow in the sunshine, and I seem to grow every five minutes.”

Her hair was lemon-juiced dirty blond, and she kept scratching at a place just above her forehead where her bangs curled down almost to her eyebrows. “Named for the flower, ’cause my ma tells me that I grow in the sunshine, and I seem to grow every five minutes.”

“If you don’t say the password, I’ll cut your throat as soon as I look at you,” Sumter snarled. He advanced on her with a rusty trowel, waving it threateningly. “No girls allowed.” He aimed the trowel at her toes and threw it hard like a spear. It missed her toes by about ten inches, landing in the moldy earth.

But the girl was already inside, sniffing the air. “I come in here lotsa times. Don’t need no password. This here’s Goober and Wilbur,” and the boys shuffled in behind her. All three wore shorts that ballooned out from their scrawny legs; the boys had no tops, but Zinnia had a sort of half top that exposed her small round belly and a series of moles like a connect-the-dot puzzle running along her back. She was ugly and pretty at the same time, which scared me. All three were dirty and sun-red and smelled just like the trash cans behind the house; I wouldn’t have been surprised to see black flies buzzing around them.

“Hey,” Goober said. He had a thick, greasy field of yellow hair on his head, practically growing out of his ears, and the biggest eyes I’d ever seen on such a small skinny face. His teeth were scummy yellow, and one of the front top ones was chipped.

Wilbur, dark and hungry looking, didn’t say a word. He had mud on his feet up to his calves. Three scars were raked across his stomach.

“I know you put that word there,” Zinnia said, tapping the back of the door. She traced her finger along the curlicue lines of the Day-Glo cuss word. “And I know what it

means

.” Then she lifted her half top up to expose her mosquito-bite nipples and said, “I even done it before.”

means

.” Then she lifted her half top up to expose her mosquito-bite nipples and said, “I even done it before.”

Drool spilled from the side of Goober’s mouth as he said, “We all done it. You like her?”

I’d never seen Sumter so contained. “I

said

get out. And put those titties away, willya?”

said

get out. And put those titties away, willya?”

“It’s a free country,” Zinnia sniffed, lowering her top again over her chest. She gave Sumter a face and then looked the two of us over. “You own this place?”

“We own this property, and you’re trespassing.”

Wilbur grunted, turning back to the door, but Goober grabbed his arm. “Ain’t goin’ nowhere.”

“We declare war on you and your kind,” Sumter said calmly. He looked at me, nodding. “This here’s our clubhouse.”

Zinnia shot me a blank stare. “That right? Can we join your club?”

“Trash is all you are,” Sumter muttered.

“What if I was to show you something?”

“I don’t want to see your mealyworm itty-bitty-toilet-paper titties again.”

“I can do something. Like a trick.”

“Baloney.”

“Just watch.” Zinnia scrambled around in the dirt, picking up old broken clay pots and tossing them before finding what she wanted. She held something small and shiny up to the light—a piece of broken glass. She turned it back and forth in her fingers and then placed it on her tongue, which she rolled up. Then she shut her mouth and swallowed the glass.

Wilbur began clapping, hopping up and down, a smile like a jack-o’lantern slicing across his face.

“

Je

sus.” Sumter screwed his face up in distaste. “I told you they were

geeks

. You in a freak show or something?”

Je

sus.” Sumter screwed his face up in distaste. “I told you they were

geeks

. You in a freak show or something?”

When Zinnia smiled again, her tongue was red with blood. “Zinnie’s real good at tricks,” Goober said solemnly. “She’s gonna be on TV or something one day and real rich and famous and livin’ in Hollywood.”

Then Zinnia, clutching her throat, rasped, “Oh, help me,

help

me.” Her fingers scratched into the skin just below her chin. But then she was laughing. “Just teasin’ you, just teasin’ you,” and she held up the piece of glass, tossing it back in a corner. She hadn’t swallowed it after all. “I can make coins disappear, too. All kindsa things.”

help

me.” Her fingers scratched into the skin just below her chin. But then she was laughing. “Just teasin’ you, just teasin’ you,” and she held up the piece of glass, tossing it back in a corner. She hadn’t swallowed it after all. “I can make coins disappear, too. All kindsa things.”

Sumter sighed. “I just wish you’d make

yourself

disappear.”

yourself

disappear.”

She turned to me. “Is he always so foul?”

But I was watching her mouth: Her teeth were red from blood. “How’d you make your mouth like that?”

Other books

SHUDDERVILLE FIVE by Zabrisky, Mia

Understudy by Cheyanne Young

The Hilltop by Assaf Gavron

Lie with Me by M. Never

The Redemption by S. L. Scott

The Rotation by Jim Salisbury

The Price Of Darkness by Hurley, Graham

Claws! by R. L. Stine

Nightshade City by Hilary Wagner