Neverland (31 page)

Authors: Douglas Clegg

I was puzzled. I looked out through the storm and saw nothing but gray rain.

Grammy Weenie continued, “Her imagination, Beau, her visions. It is part of the Wandigaux line. I have had them, and I know you have your dreams, don’t you? You used to tell me your dreams when you were four and five, and then you stopped. You did the right thing, child, because it never does one good to let these things out into the world. It is like the blue of our eyes: handed down. And she would’ve been fine, too, but Lee was worried about her fits of depression and anger. She was backward and slow, and he hated her for it. God, how he hated her for it. Old Lee was not understanding of differences, of the unusual. But then, he was not a Wandigaux.

“Old Lee could not suffer her moods any longer, may God forgive him, and he had this, this

quack

, perform an operation on her. This horrid doctor. To—to take out the emotions from her head. He swore he was only

removing the part of her that hurt. That carpetbagger from Boston, he swore she would never hurt again. But I tell you. Beau, after he stuck his needles beneath her scalp, above her eyelids,

all she did was hurt

. There was no hope for her then. None. They say humans can’t live without hope, but she did. Oh, yes. She lived. She spent nights out in that shack. She worshiped what none could see, but she saw. She saw. All around us, an invisible world. The world is a skin, and she was able to hack at the flesh of life to the beating heart, and no man or woman should ever do that. It is forbidden to us. Children came to her. I saw her playing with them out in the woods, teaching things children should not learn. And one by one those children died, swimming into a rough surf, swimming away from the something that came toward them. And Lucy, my daughter, who had been merely slow, merely

different

before her surgery, after . . . after . . . she was a monster. She said the children were infested and that the sea would cleanse them. She laughed as they went under.”

quack

, perform an operation on her. This horrid doctor. To—to take out the emotions from her head. He swore he was only

removing the part of her that hurt. That carpetbagger from Boston, he swore she would never hurt again. But I tell you. Beau, after he stuck his needles beneath her scalp, above her eyelids,

all she did was hurt

. There was no hope for her then. None. They say humans can’t live without hope, but she did. Oh, yes. She lived. She spent nights out in that shack. She worshiped what none could see, but she saw. She saw. All around us, an invisible world. The world is a skin, and she was able to hack at the flesh of life to the beating heart, and no man or woman should ever do that. It is forbidden to us. Children came to her. I saw her playing with them out in the woods, teaching things children should not learn. And one by one those children died, swimming into a rough surf, swimming away from the something that came toward them. And Lucy, my daughter, who had been merely slow, merely

different

before her surgery, after . . . after . . . she was a monster. She said the children were infested and that the sea would cleanse them. She laughed as they went under.”

I gasped, “Zinnia and her brothers.”

Grammy Weenie continued, “I have the sight, child, but it is faulty and I often wonder if it is anything more than a strong intuition. But Lucy had what Sumter has. The full Wandigaux curse. You can go back hundreds of years and find it, back to France when certain members of our family were tortured for conjuring. It doesn’t go with everyone. You may have a little—I’ve always felt you do. But your sisters are lacking, as are your mother and your aunt, as far as I have been able to tell.”

“I do have dreams, sometimes,” I whispered, but she didn’t seem to hear me. It was as if I wasn’t there at all, and I had tapped into some inner fountain of my grandmother’s memory—something she could not hold back when it was touched on.

“And it is a curse, not a blessing,” she said, and I felt a chill as she spoke. It was as if she were speaking to a ghost. “Lucy never saw the world as it was, only as she created it in her mind. She stayed a child up until her death, even though physically she should’ve been a woman. Beau, you have to cross that bridge into the world, and Lucy could not.”

She nodded several times; I thought she had gone insane as she ranted. “The Gullahs here know about her, what she did. They know. They know how gods mate with humans, they know both the visible and invisible world. They have stories . . . they have stories about seeing what can’t be seen. Most of my life, child, I was taught that the church was the dwelling place of God. I have no doubt he has other places, also, be they temples, mosques, or tents. But who would’ve thought there would be other gods? That there are cathedrals for these gods? And what that doctor did with his needles, with his scalpels, with his

drugs

was to cut a peephole through the altar of some creation other than our own.”

drugs

was to cut a peephole through the altar of some creation other than our own.”

My grandmother went silent. I was about to say something, but I felt invisible fingers along my back, a terrible chill, and the confusion of her words as they poured from her mouth.

“We see only what we need to see to survive. Who is to say there is not another world moving all around us to which we are blind? And perhaps until we enter that world, its inhabitants, also, are blind to us. Lucy! Oh Lucy!” Grammy Weenie bleated. “Lucy became a bride of a god—a terrible, savage god. And she bore children, yes,

children.

Two. First, one which was more her blood than its father’s, a child she named Summer for the season in which he arrived. Old Lee and I cared for him and hid our shame from the rest of the world. But within a year, in spite of our watching Lucy as much as we could stand to, she bore another. The second was more his father’s son . . . ”

children.

Two. First, one which was more her blood than its father’s, a child she named Summer for the season in which he arrived. Old Lee and I cared for him and hid our shame from the rest of the world. But within a year, in spite of our watching Lucy as much as we could stand to, she bore another. The second was more his father’s son . . . ”

Here, Grammy’s voice faltered, and I would not have been surprised if there were tears in her eyes, but in the lightning, I saw that her eyes were clear, her gaze steady. I could tell that she’d repeated these words to herself many times over the past ten years, and only now, in that instant, was she prepared to accept the truth in them.

“The child was . . . beast and human, male and female, an abomination, and yet . . . it had her eyes . . . my eyes . . .

Wandigaux

eyes. I saw it. I saw her give birth, bellowing like a heifer, on her side, the child emerging, his

face covered with a caul, but beneath it,

eyes.

Our eyes. I was all prepared to kill it. Snuff out its life quickly, the way I had years before helped my father kill a calf that had been born with two heads. Kill it because it didn’t belong in our world. But those eyes. Beau, what was I to do? Human eyes, and Wandigaux eyes. I felt it was in God’s hands, that He would take care of the child.

Wandigaux

eyes. I saw it. I saw her give birth, bellowing like a heifer, on her side, the child emerging, his

face covered with a caul, but beneath it,

eyes.

Our eyes. I was all prepared to kill it. Snuff out its life quickly, the way I had years before helped my father kill a calf that had been born with two heads. Kill it because it didn’t belong in our world. But those eyes. Beau, what was I to do? Human eyes, and Wandigaux eyes. I felt it was in God’s hands, that He would take care of the child.

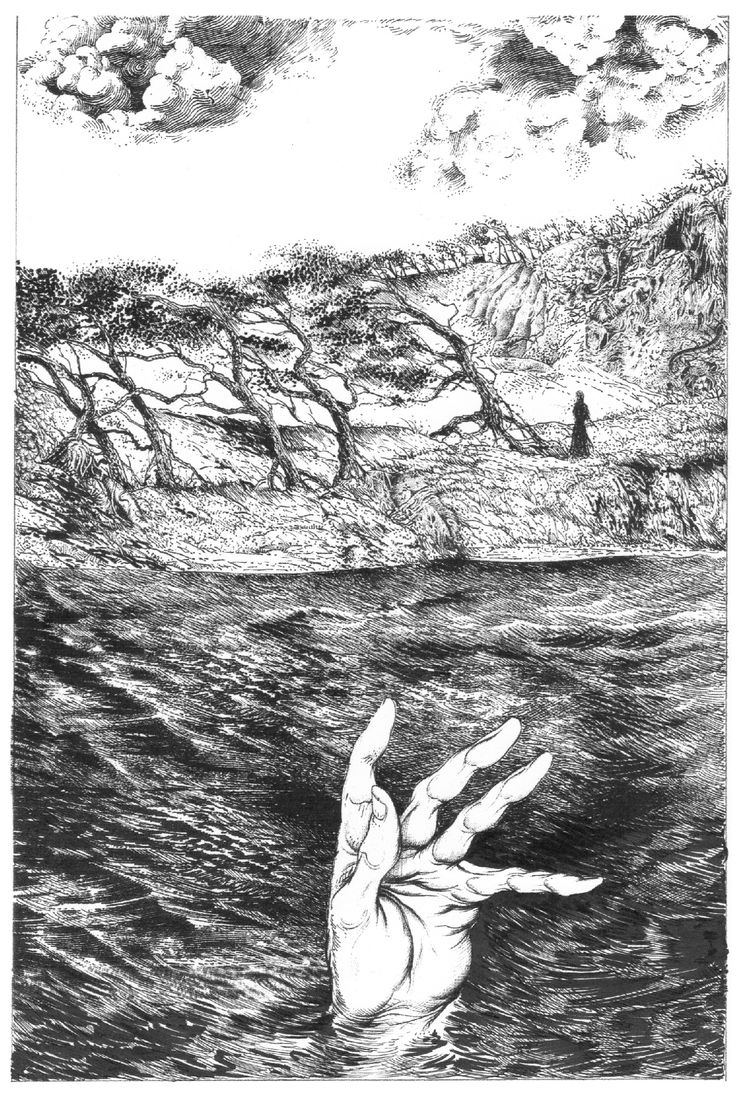

“And then I found her, one day, out on the bluffs, and I heard the horrible screaming, and I ran—it was the sound of a baby crying for dear life, and I ran until I fell, and I saw her there, by the shack.

What she did.

Unnatural. I could not . . .

stand

. . . I could not

stand

my own

child.

Devouring her newborn. Even . . .

it . . .

this baby

deserved

. . . it was a freak of nature . . . but even

it

deserved a better mother, even

it . . .

And I was too late.

What she did.

Unnatural. I could not . . .

stand

. . . I could not

stand

my own

child.

Devouring her newborn. Even . . .

it . . .

this baby

deserved

. . . it was a freak of nature . . . but even

it

deserved a better mother, even

it . . .

And I was too late.

“But in the basket beside her. The other. Summer. Her firstborn. Eleven months old with blood on his forehead. My Babygirl was going to devour him, too. The rake. I saw the rake. I had raked that garden with it. It was old and rusty, but good. I only saw the rake. I held it in these two hands and stopped my Babygirl from what she was about to do with her first child. Her skull was crushed. And she had not let out a whimper or a cry, and I knew that her soul had been released from the awful torment of its earthly cage.”

As if to myself, I said aloud: “Summer

is

Sumter.”

is

Sumter.”

“Your mother and your aunt never knew how she died—they were both newlyweds and busy with their lives. Cricket married her husband the previous spring and miscarried in her fourth month. I brought your cousin to them, and they adopted him. I told them that Babygirl had died because of complications relating to her surgery, and no one was surprised. Life does continue.

“Your dreams, Beau, are like mine. We see things that may come. But Sumter has more. He can make things happen. He can

change

things. And it was all safe, but now it’s free. Madness can be its only name.”

change

things. And it was all safe, but now it’s free. Madness can be its only name.”

“But it does have a name,” I whispered. “Neverland.”

“Yes.” Her voice was ice and fire at the same time, and then it became the barest of whispers. “Sumter could keep it there, keep it in that shack, where his mother played. It was safe. But no more. No . . . more.”

9I was exhausted that night, and I believe it must’ve been two a.m. when I finally crawled into bed. I knew I would not sleep. The visions—of a ghost, of Lucy coming from her desecrated shrine, coming for the child who had not made the sacrifice as promised to her, of the dead creatures from the crate slithering up the stairs toward me, of my premature burial out in the mud of that shack, and of bony fingers pulling me down further into a rotting embrace—all kept pounding against my eyes.

Lightning and the booms and crashes of wind and branches and thunder outside, the rattling of the screen at my window—all of it slapped at my brain.

I tried shutting my eyes, but it hurt more to keep them shut than to keep them open. When lightning lit up the corners of the room, I saw Sumter standing there.

“You are the destroyer of the temple,” he said. “You are the blasphemer of Lucy.”

“I know who Lucy is, Sumter. Lucy is not a god!”

“Shut up!” he shouted, and drowned me out with his cries.

Behind him, a hulking shadow, and the smell of a wild animal.

I sat up in a cold sweat. I awoke. I had been dreaming. Sumter was not in my room at all. I got up to use the bathroom, feeling my way along the walls. How would I pee? I would have to take good aim in the dark. Afterward I went to check on Governor. He was not in his crib, and I panicked until I heard my mother’s voice.

“Who’s that?”

“Me.”

“Beau? You should be in bed.”

“I want to make sure Governor is okay.”

“He’s right here, with me. He’s fine.”

“Okay. Just checking.”

“Beau, we’ll leave here tomorrow. When your Daddy comes back from St. Badon.”

“He’ll be back early. He promised. Don’t worry, Mama.”

“I know. Go back to sleep. Get some rest.”

I tiptoed back down the hall. I thought I saw someone sitting on the stairs, but I chose not to investigate this. I lay in bed until dawn, not sure if I was sleeping or not.

When I awoke, it was because a woman was screaming.

10Aunt Cricket had three kinds of screams: the shrieky kind that meant someone had gotten into something he wasn’t supposed to; the high-pitched cat squeals like she’d just tripped on something or gotten bit by a yellow jacket; or the one I heard this particular morning, which meant something had just scared the bejesus out of her. “Sunny! Sunny!” she keened, and I heard her clopping horseshoe steps all along the hallway; she was dashing down stairs, then up. I heard doors fling open, until finally she came to mine. “Sunny! Sunny! You seen him? You seen him, answer me, will you?”

I shook my head. After she ran off down the hall, I got up and got out of my underwear and into my trunks. I went out in the hall, and wondered why Governor wasn’t crying the way he usually did in the mornings.

Mama was in her room, crying as she pulled her clothes on. Nonie and Missy were standing around looking lost. Mama said, “He was right

here

,” indicating, with a nod of her head, a small oval lump on her bed. “I just got up for a second to get some water. My throat was parched. I was only gone for a minute.”

here

,” indicating, with a nod of her head, a small oval lump on her bed. “I just got up for a second to get some water. My throat was parched. I was only gone for a minute.”

My worst fear was realized.

Governor. SUMTER, DON’T YOU DARE!

“What time is it?” I asked my sister impatiently.

Nonie glanced at her watch. “Jeez, it’s five to ten.”

“Why’s it still so dark out?” Missy asked.

“Must be the storm. Clouds and stuff.”

“He’s taken Governor,” I said, gasping. “He’s gonna sacrifice Governor.”

I ran past them, down the stairs. Grammy Weenie was out on the porch, her hair greased and batted down by the rain, her face white and empty. “Why didn’t you stop him?” I asked.

“The trees,” Grammy hung her head low, defeated, “the trees were screaming, the light . . . changed . . . I saw behind the trees, I saw what walked . . . what walked in their shadows . . . his face. His face. The Feeder. Oh, dear God, the face of madness. Starved, coming for me.”

“He took—” I caught my breath; she was not even listening.

“I was watching. For her. For my lost daughter. I felt she was coming back for me, last night.” Grammy tapped the silver brush in her lap. “All night I felt her. But she has won. We are in Neverland now. For all I know, the whole world is Neverland.”

Missy squealed from the upstairs window: “Jesus! Somebody pulled the plug on the ocean or something!”

I went running out to the bluffs through the storm. The rain came down in sheets. I was soaked through by the time I made it out to one of the trees. I climbed up to its lowest branches, and clung to them even as the wind bent the tree over. My father was going to cross the bridge at any moment, he was going to flash his headlights, but as I looked out over the sea to the bridge, I saw what Missy meant.

The tiara bridge was overtaken by an enormous wave, and the peninsula itself seemed to be separating from the mainland, to become what it was intended.

An island.

TWELVE

Where I Am Is

Neverland

1Neverland

There is no tyranny like a child’s imagination, and all my cousin Sumter could imagine was encompassed within Gull Island. Grammy Weenie had been right when she said,

“Don’t let it out.”

He had kept it contained within that crate, within those walls of Neverland. Now that sacred place had shattered, and the fragments, like jagged glass arrows, had flown out in all directions.

“Don’t let it out.”

He had kept it contained within that crate, within those walls of Neverland. Now that sacred place had shattered, and the fragments, like jagged glass arrows, had flown out in all directions.

Other books

Power & Beauty by Tip "t.i." Harris, David Ritz

Round the Bend by Nevil Shute

Chardonnay: A Novel by Martine, Jacquilynn

The Sword of the Lady by Stirling, S. M.

Wounded Wings (Cupid Chronicles) by Allen, Shauna

Blood and Ashes by Matt Hilton

I Haiku You by Betsy E. Snyder

The Valley of Unknowing by Sington, Philip

Mammoth Secrets by Ashley Elizabeth Ludwig