Neverland (34 page)

Authors: Douglas Clegg

“Like what?” Aunt Cricket cornered her. “Like what, young lady?”

“Like he is,” she spat, her words running together in one long string. “Killing and stealing and praying in his clubhouse. We didn’t mean to drink the beer that time, or steal cigarettes and stuff, but he made us, he made us, and I never wanted to hurt anything, and he made us see things and feel things, and then writing in blood, and all—”

Nonie wanted to cut out Missy’s tongue. “Don’t tell them

everything.”

everything.”

“It’s over, don’tcha get it?” Missy’s eyes were all squinty and her nose was a wrinkled bump with two flared nostrils; her lips had gone purple and blubbery. “You

know

what he’s gonna do to Governor, they gotta try to stop him.”

know

what he’s gonna do to Governor, they gotta try to stop him.”

Mama said, “What about the baby?”

Missy was crying too hard to make any sense.

Mama turned to Nonie, “What about the baby?”

“He isn’t gonna do it, don’t worry. Mama don’t cry, he isn’t gonna do it.”

“Do what? Tell me now.”

“There’s no

way

he’d hurt Governor.”

way

he’d hurt Governor.”

Aunt Cricket slapped Nonie. Nonie was always headstrong, and this was the second time in the last ten minutes she’d gotten slapped, and she slapped Aunt Cricket right back, which didn’t go over too well with either grown-up, but they put the question to her—the punishment, Mama promised, would come later. So Nonie told them about the big sacrifice, and how I had run out of the house when the bridge washed out yelling about how Sumter was going to use Governor for the sacrifice.

“My Sunny would never do that kind of filthy thing,” Aunt Cricket admonished my sister. “You’re just Little Miss Liar, Leonora Jackson, and that’s all you are.”

“I

said

he wouldn’t really go through with it. He wouldn’t kill a

baby.”

said

he wouldn’t really go through with it. He wouldn’t kill a

baby.”

But Mama was already headed down the staircase, saying, “I’ll get Beau, he’ll know. He always watches out for his brother, he’ll know.” That’s when she headed out the front door and stumbled out through the storm to the remains of Neverland.

Missy ran past Aunt Cricket to get to her bedroom. She escaped our aunt’s wrath, but Nonie did not.

“You’re just Little Miss Liar, I know you.” Aunt Cricket grabbed Nonie by the wrist and dragged her along the hall with her. “You’d like to make out like my boy is a bad boy, but I know what’s true and what’s not.”

“Let me go.” Nonie scratched at our aunt’s arm with her free hand, and Aunt Cricket hauled off and slapped her one again. Nonie struck back again, kicking Aunt Cricket in the shins and then scampering off to the safety of the closest bedroom, which just happened to be Grampa Lee’s old room, which was an unwise choice on her part.

Uncle Ralph occupied that room. He was sitting up in bed in his boxers and a tank T-shirt, practically scratching his balls. It was ten a.m., but he still had a Dixie beer clutched in the hand that wasn’t scratching. Six empties were overturned on the rug near his puffy feet.

“You kids’s nothin’ but trouble,” he said, belching. “Nobody should have kids, nobody, understand?”

Nonie had her back up against the door. Aunt Cricket was banging on it from the other side, telling her in no uncertain terms to open up.

Uncle Ralph yelled at his wife, although Nonie figured he might be yelling at her, too. “You can just go off with Mr. Goody-Two-Shoes Dabney Jackson and give birth to some more village idiots, for all I care! You got that, Crick?”

But Aunt Cricket had her one goal: to get Nonie for kicking her. She shoved hard on the door and it gave a little, but Nonie held her ground and shoved back. “Little Miss Liar, you let me in right this instant.”

And between Uncle Ralph shouting obscenities and Aunt Cricket pushing on the door, Nonie saw something battering at the bedroom window that made her scream.

It was a little girl, floating in midair, slapping hard at the glass. Nonie knew the girl: It was herself, only she was blackened as if from fire, and

the only way Nonie recognized it was her and not Missy or somebody else was through the eyes. In her mind Nonie heard Sumter’s voice saying,

Lucy wants it all, now.

the only way Nonie recognized it was her and not Missy or somebody else was through the eyes. In her mind Nonie heard Sumter’s voice saying,

Lucy wants it all, now.

But the girl at the window flew away and off into the storm again.

Aunt Cricket was distracted and turned away from the door because of Grammy Weenie shouting that something was going on over at the bluffs, and then a while later Julianne was bringing me back inside, and Missy was sure I was dead, but Nonie told me later that she knew I was alive on account of she heard me coughing. She went back and hid with Missy while Uncle Ralph ran out, practically tripping down the stairs, to bring Mama back, too.

My sisters watched as I came to, and they eavesdropped on everything that was said between Grammy, Julianne, and me. When Aunt Cricket started running a hot bath for Mama, she seemed to have forgiven Nonie the kick long enough to enlist her aid. “Get some clean towels—the large ones—out of the linen closet, and I can’t find iodine, so if you know where it is, bring that, too. Your mama’s all scratched up and I need to clean the cuts out.” Nonie did as she was told, afraid that Mama was never going to come back from the place her mind had sent her to.

Missy kept saying, “It’s ’cause we been worshiping the Devil.”

Nonie tried to shush her, but Aunt Cricket latched on to that. “You brought that kind of stuff down from

Virginia,

didn’t you? My boy wouldn’t’ve learned that Devil stuff in Marietta, let me tell you. You bad, bad little girls.”

Virginia,

didn’t you? My boy wouldn’t’ve learned that Devil stuff in Marietta, let me tell you. You bad, bad little girls.”

Nonie would’ve contradicted her, but she figured she was already in enough hot water as it was. Then she noticed something about Aunt Cricket, something she hadn’t noticed until now. Aunt Cricket had a shadow, in the dim light—a long shadow just like it was late afternoon—and the left hand of Aunt Cricket’s shadow seemed to move differently than Aunt Cricket’s own left hand.

“Mama,” Nonie whimpered. Mama had crawled over to a corner of the bathroom. She was surrounded by steam, so Nonie could just make out her

face. Aunt Cricket was running the water so hot, Nonie thought it actually might be boiling. Even in the steam Aunt Cricket’s shadow moved and grew, and Nonie wondered why nobody else seemed to notice. Mama wasn’t recognizing anybody, but she kept asking for her baby, her little baby boy, and wiping at her face like she wanted to scrape the skin off. Aunt Cricket was barking orders and trying to get Mama to sit up. “C’mon, Evvie, just so I can get your blouse off, and Nonie, where

is

that first-aid kit? How many times do I have to ask for it?” The shadow didn’t wag her finger at Nonie; the shadow seemed to be dancing around in a jig, still attached to Aunt Cricket.

face. Aunt Cricket was running the water so hot, Nonie thought it actually might be boiling. Even in the steam Aunt Cricket’s shadow moved and grew, and Nonie wondered why nobody else seemed to notice. Mama wasn’t recognizing anybody, but she kept asking for her baby, her little baby boy, and wiping at her face like she wanted to scrape the skin off. Aunt Cricket was barking orders and trying to get Mama to sit up. “C’mon, Evvie, just so I can get your blouse off, and Nonie, where

is

that first-aid kit? How many times do I have to ask for it?” The shadow didn’t wag her finger at Nonie; the shadow seemed to be dancing around in a jig, still attached to Aunt Cricket.

“Your . . . your shadow,” Nonie stammered.

Aunt Cricket said, “Will you go get the first-aid kit? Will you?”

Nonie ran out into the hall with Missy tagging along. The first-aid kit was kept in a shoe box in the linen closet. As the girls opened the doors on the closet, they heard something shuffling toward the back. Nonie reached as far as she could to the back of the closet for the shoe box when something touched her. It was soft and furry and warm, but it reminded her of when she put her hand in the Neverland crate, and she tried to draw her hand back from the shelf, but the creature held her. It had claws that began digging into her hand.

“Jesus!”

she yelped, falling backward as the thing let go of her. While Missy went scrambling for the stairs, Nonie looked at the back of her hand. It was practically scraped raw, although the claws hadn’t dug as deep as she figured; only the top layer of skin was gone. Her hand didn’t hurt so much as feel numb, and she got up as quickly as she could to shut the closet doors, when the creature leapt out at her and she hit her back on the floor so hard she was sure her tailbone was broken.

she yelped, falling backward as the thing let go of her. While Missy went scrambling for the stairs, Nonie looked at the back of her hand. It was practically scraped raw, although the claws hadn’t dug as deep as she figured; only the top layer of skin was gone. Her hand didn’t hurt so much as feel numb, and she got up as quickly as she could to shut the closet doors, when the creature leapt out at her and she hit her back on the floor so hard she was sure her tailbone was broken.

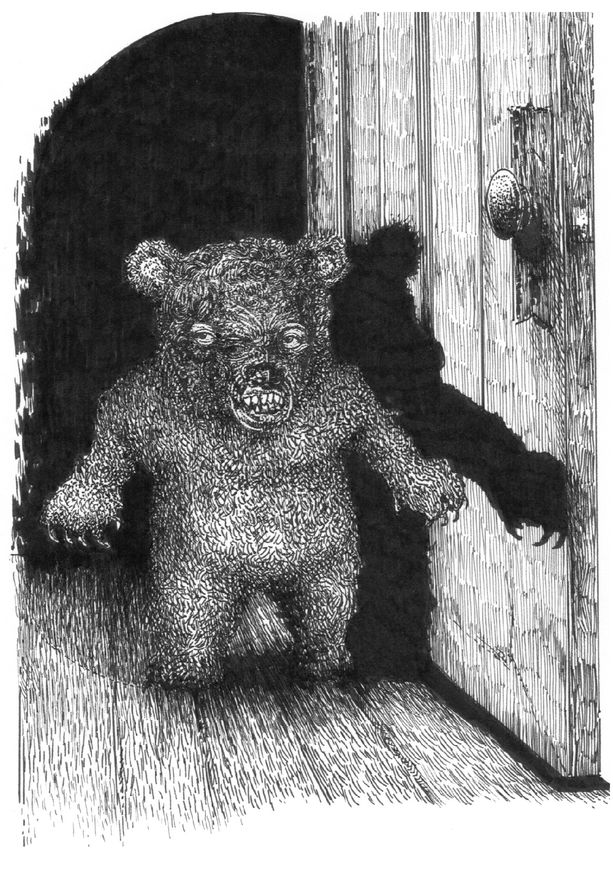

Its furry paws clutched her throat.

It was the teddy bear.

Bernard.

He stared at her with his blank button eyes, his muzzle curled in a snarl, his teeth dripping with foam.

From the living room we heard the screams, and Missy would’ve gone flying past us and out the front door, but Julianne shot up and caught her by her shoulders as she ran by. “Let me go, it’s awful, let me go, they got Nonie!”

Nonie was screaming, and I tried to get up, but damn if my body was unwilling: My limbs were slack. I tried to will the pins-and-needles feeling of circulating blood through me, but my arms and legs were frozen. Nonie was now crying out in little gasps, and Julianne let go of Missy and headed for the staircase. Missy went to cry on Grammy’s lap.

I was thinking what Sumter had told us, that one of Lucy’s commandments was

Do what you will.

So if Neverland was the whole world around us, then, hell, I was going to

will

my body to move in spite of itself.

Lucy, come on, get my blood going, come on.

Do what you will.

So if Neverland was the whole world around us, then, hell, I was going to

will

my body to move in spite of itself.

Lucy, come on, get my blood going, come on.

Aunt Cricket was freaking out in the bathroom. Nobody’s really sure what happened with her and the bathroom door. There’s a good chance she went to help Nonie but the door slammed in her face and maybe threw her back against the wall. The last thing Nonie saw was just a glimpse of the black glove shadow hand on the doorknob. No sound from her after that, but then everybody was screaming so much, who really knows?

But after another moment we heard Aunt Cricket cackling, “Take a hot, hot, hot bath, soothes the nerves, don’t it? A boiling hot bath,

take the skin right off you! Get you all nice and

clean,

scrubbadubdub, just like you was a crawdad in a pot, all red and hot, hot, hot!”

take the skin right off you! Get you all nice and

clean,

scrubbadubdub, just like you was a crawdad in a pot, all red and hot, hot, hot!”

Uncle Ralph came out in the hall blustering and babbling, “What the hell is goin’ on

this

time?” He beat his fist on the bathroom door, and Aunt Cricket began shouting at the top of her lungs,

“Cleanliness is next to godliness. I’m just washin’ all my sins away in the river that burns eternal, hallelujah, amen!”

this

time?” He beat his fist on the bathroom door, and Aunt Cricket began shouting at the top of her lungs,

“Cleanliness is next to godliness. I’m just washin’ all my sins away in the river that burns eternal, hallelujah, amen!”

“Just turn it down, woman,” he muttered. “Off her rocker, for sure.” When Uncle Ralph saw what Nonie was shrieking about, there at the end of the hall, he almost laughed. Even though the bear had ripped through her shirt and left a bloody claw mark down her stomach.

Seeing Uncle Ralph, the bear stopped, and Nonie said she was sure the bear was just going to slice her in two. But it sniffed at the air. It

turned and looked back at Uncle Ralph and crawled off her. She used her hands to pull herself up. By that time Julianne had grabbed her up in her arms.

turned and looked back at Uncle Ralph and crawled off her. She used her hands to pull herself up. By that time Julianne had grabbed her up in her arms.

“Sure must be on some damn bender,” Uncle Ralph laughed, “ ’cause these DTs are a bitch.” He wasn’t exactly seeing straight because he kept wobbling from side to side, trying to get a take on the bear.

The bear growled, and Sumter spoke through it:

“Vengeance is mine, mine, and all mine, you hear? You’re in

my

playground now, and here

you’re

the weak sister.”

“Vengeance is mine, mine, and all mine, you hear? You’re in

my

playground now, and here

you’re

the weak sister.”

The teddy bear advanced on Uncle Ralph. It moved clumsily, wobbling on its flat round feet. Maybe if Uncle Ralph hadn’t been so drunk he might’ve just gotten around Bernard, but Ralph stood stupidly and watched the bear approach him. He didn’t even get it. There was his wife screaming in the bathroom and his niece with her shirt torn, and Uncle Ralph just had a slap-happy grin on his face that didn’t change. He thought it was some kind of joke or dream.

He plopped down on the floor like he wanted to play with the bear. “Boy’s too old to be playing with dolls.”

The teddy bear climbed almost sweetly into his lap, and Uncle Ralph hugged it. “I guess ain’t no harm in a teddy bear,” he said.

“This is the way we wash our skin, wash our skin, we wash our skin!”

Aunt Cricket howled from the bathroom.

Aunt Cricket howled from the bathroom.

Nonie said Julianne screamed and almost dropped her then, on account of the bear tearing into Uncle Ralph’s throat and all the shooting blood.

Up until the last, Uncle Ralph looked like he thought he was still dreaming, and only during his last second of life did it seem to occur to him that a dream wouldn’t hurt so much.

6“Beau?” Julianne called from the upstairs landing. “If you can, you get that croquet mallet I left by the couch and you bring it up to me.”

I was still fighting my blood, but I was willing it. I was going to control my mind, I was going to make my body do what I wanted it to do. I saw in my mind’s eyeball my heart pumping and my toes wiggling. I blocked out Missy’s whimpers and Grammy’s fever-pitch prayers and just saw my body working the way it was supposed to.

I was able to raise my hand.

“Beau!” Julianne shrieked, and I was up like a shot. I grabbed the mallet and practically tripped over my feet before I got my balance.

Julianne was backed up against the bathroom door with Nonie hugging her tight around the neck. The door wouldn’t budge, and the bear, having done a messy job of severing Uncle Ralph’s head from his neck, was advancing on her.

“Beau? You got it?”

When I came up the stairs, I thought I was going to throw up. Uncle Ralph’s legs and arms were still twitching, and the stench was overpowering. I slammed the mallet against the banister, cracking it.

Other books

Witchlanders by Lena Coakley

Boxcar Children 54 - Hurricane Mystery by Warner, Gertrude Chandler

Engleby by Sebastian Faulks

Fool's Gold by Jaye Wells

Sex, Love, and Aliens 2 by Imogene Nix, Ashlynn Monroe, Jaye Shields, Beth D. Carter

Banished by Tamara Gill

Daughters of the Dragon: A Comfort Woman's Story by William Andrews

Dart and Dash by Mary Smith

Amped by Daniel H. Wilson

The Arrangement by Bethany-Kris