New York at War (14 page)

Authors: Steven H. Jaffe

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #United States

For many frightened New Yorkers, the pieces were all falling into place. The New York plot—“one of the most horrid and detestable pieces of villainy that ever Satan instilled into the heart of human creatures,” Judge Daniel Horsmanden called it—was no doubt part of a global Catholic conspiracy to incite these “latent enemies amongst us,” “these enemies of their own household,” to literally stab their masters in the back.

39

Horsmanden, one of three Supreme Court Justices, refused to believe that black slaves—“these silly unthinking creatures”—or a mere tavern keeper like Hughson was capable of launching such a shrewd plot. “There is scarce a plot but a priest is at the bottom of it,” Horsmanden concluded, and the city authorities began a roundup of suspected secret Catholics. Four Irish-born soldiers from Fort George were arrested; to save himself, one of them “confessed” that a plot was afoot to burn down Trinity Church, the city’s bastion of English Protestantism. John Ury, an eccentric teacher of Latin and Greek recently arrived in the city, was arrested and accused of being a secret priest and the true ringleader of a diabolical Spanish or French plot, launched with Vatican approval, to burn New York. Horsmanden, for one, persuaded himself that a joint Catholic-slave uprising, originally planned for St. Patrick’s Day, had been coordinated by “our foreign and domestic enemies” to destroy the seaport and prevent the city’s ships from bringing food and supplies to British armies and navies fighting Spain in the West Indies. Ury’s protests of innocence could not save him from conviction or the gallows. By the time he was hanged on August 29, he joined thirty black men, two white women, and one white man (Hughson) who had already met their end; eighty-four other slaves, including many who had confessed, were ultimately banished by being sold outside the colony.

40

We will never know fully the true nature and extent of the “Negro Plot” of 1741. Some scholars have argued that militant slaves probably did plan an uprising, to coincide with a hoped-for Spanish or French invasion. More likely is the possibility that a small number of slaves set some of the fires as limited acts of resistance, rather than hatching the murderous plot imagined by panicking whites and sworn to by coerced suspects. Engaged in an imperial, global, and ultimately religious war, protected by flimsy local defenses, ever mindful of enemy privateers and the attacking fleets they might lead into the harbor, propertied white New Yorkers found it easy to detect enemies all around them: plebeian Irish soldiers in the fort, lowly tavern keepers on the waterfront, hidden priests, their own duplicitous slaves. An unrelenting Daniel Horsmanden continued to insist that the lesson of 1741 was “to awaken us from that supine security . . . lest the enemy should be yet within our doors.”

41

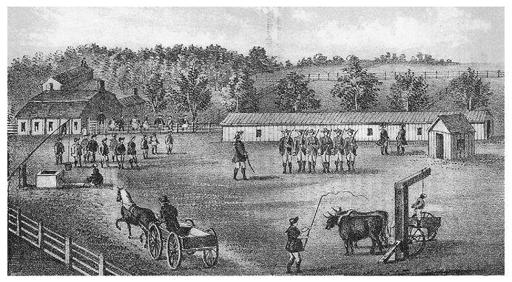

“Latent enemies amongst us.” An enslaved African is hanged on the eighteenth-century city’s outskirts. Lithograph by George Hayward,

Ye Execution of Goff ye Neger of Mr Hochins on ye Commons,

1860. AUTHOR’S COLLECTION.

Over the two decades following the events of 1741, New Yorkers would enjoy only seven full years of peace, as the British Empire fought and concluded one war against the Spanish and French, and then in 1756 commenced another one. By late 1760, however, British victories had settled the fate of Canada, vanquishing the looming French presence to the north. As redcoats and sailors left New York City by the hundreds in 1761 and 1762, off to conquer the French islands of Martinique and Dominica and to besiege Havana, New Yorkers could congratulate themselves on having survived five colonial wars without ever setting eyes on an enemy armada sailing up the bay or down the Hudson.

42

Yet for all New Yorkers’ relief, the end of the cycle of imperial wars left the city an abruptly poorer place. The removal of troops and fleets was one key factor in an economic slump that now hit New York and the other colonial ports hard. To make matters worse, Parliament decided to reorganize and increase its taxation and commercial regulation of the colonies in order to recoup some of the war’s expenses and to fund the continued British military presence on the frontier.

43

Like other American colonists, New Yorkers now brought a range of escalating grievances to their concerns about their place in the empire. Merchants and lawyers championed “smuggling” as free trade, arguing that freedom of the seas was a social good Parliament dare not strangle. Militiamen who had felt the disdain of British regulars on the Canadian front returned home to view redcoats with new eyes. Men who had learned how to fight on privateers—New Yorkers Alexander McDougall, Isaac Sears, and George Clinton among them—had taken the measure of British allies as well as French foes. McDougall and Sears would soon be leading a group called the Sons of Liberty. And young Clinton would go on to serve as New York’s revolutionary governor and under Thomas Jefferson and James Madison as vice president of a nation no New Yorker could yet imagine at the conclusion of five wars for the empire.

44

CHAPTER 4

Demons of Discord

The Revolutionary War, 1775–1783

A

ccompanied by officers and sentries, George Washington inspected his army’s handiwork in lower Manhattan’s narrow streets. It was mid-April 1776, and New York was swarming with thousands of soldiers pledged to fight king and Parliament. Log barricades now extended across Wall Street, Crown Street, and a dozen other waterfront thoroughfares, while redoubts of freshly turned earth sheltered artillery batteries along the wharves and on the crests of hills beyond the city’s outskirts. Washington’s second in command, General Charles Lee, had followed his orders conscientiously, arriving in Manhattan with a thousand Continental soldiers and militiamen in order to turn the city into “a disputable field of battle against any force.” Lee, known for his political radicalism and his hatred of British loyalists, had ordered New York City’s male population to help in the effort. Mustered every morning by a fife and drum corps, one thousand civilians—leather-aproned artisans, merchants and shopkeepers, slaves delivered up by their masters—took their turn at the shovel and the axe. One of Washington’s generals noted approvingly that the wealthiest men “worked so long, to set an example, that the blood rushed out of their fingers.”

1

If Washington feared that these defenses might prove flimsy against the full brunt of the British Empire’s might, he most likely kept those fears to himself. The general was still learning to command an army whose ranks were filled with amateur soldiers. One year earlier, in April 1775, war had broken out when British troops had faced minutemen at Lexington and Concord. Two months later, Washington assumed command of the American troops surrounding Boston’s peninsula, where the British commander, General William Howe, had entrenched his army after the Battle of Bunker Hill. When Howe put his troops on transport ships and sailed away in March 1776, Washington strongly suspected that Howe’s next landfall would be Manhattan Island. By that time, Washington had already sent Lee south to prepare New York City for invasion. In fact, Howe’s destination was Halifax, Nova Scotia, but Washington’s foreboding was correct: Halifax was merely a provisioning station and rendezvous for the grand expeditionary force Howe was mobilizing for an assault on Manhattan.

Washington had consulted with the Continental Congress before marching and shipping his entire army two hundred miles south from Massachusetts. Washington believed strongly that New York City was crucial to American victory in the war. Congress agreed. Writing to the general from Philadelphia, John Adams concurred that New York was “a kind of key to the whole continent.” In believing this, Washington and Adams were merely echoing what had been obvious in North American and European strategic thinking for a century. Whoever controlled the Hudson River between its southern terminus at New York City and its northern borderland in Canada not only possessed one of the continent’s great water highways but also held the natural boundary separating New England from the Middle and Southern colonies. For Howe to seize New York City would raise the specter of an impregnable British line stretching from Manhattan to Montreal and Quebec, geographically cutting the revolution in two and making it that much easier to quash.

2

With congressional consent secured, Washington made New York his new base of operations. By his own arrival there on April 13, over fourteen thousand American troops—most of them veterans of the Boston campaign—had already filled makeshift camps in and around the city, while thousands more were making their way on foot or by boat from Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Jersey, Long Island, and the Hudson Valley. The city awed Washington’s soldiers, most of them farm boys who had never encountered a place so large or so cosmopolitan. Ensign Caleb Clap from Massachusetts was intrigued by the services he attended in the city’s synagogue and Lutheran church. Clap’s commanding officer, Colonel Loammi Baldwin, a young land surveyor from Woburn, wrote to his wife of another of the city’s attractions: the “bitchfoxly jades, jills, hags, strums, prostitutes” he encountered while on duty in the city’s brothel district west of Trinity Church. The soldiers commandeered houses, many of them abandoned by fleeing civilians, and hunkered down in barns and tents from Paulus Hook on the New Jersey shore to Red Hook on the Long Island shore. “Our tent living is not very pleasant,” wrote Philip Fithian, a young army chaplain with a New Jersey regiment stationed at Red Hook. “Every shower wets us. . . . But we must grow inured to these necessary hardships.”

3

By the 1770s, New York was a city of over twenty thousand, home to a jostling array of peoples and interest groups; its rural environs across the harbor and in northern Manhattan consisted of tidy farms and small hamlets linked to the city by roads and waterways. The town had continued to grow through the mid-century cycle of war and peace, extending north beyond Stuyvesant’s old defensive wall, which had fallen into disrepair by 1699 and soon disappeared as New Yorkers used its wood and stone for new buildings. On some blocks, elegant brick townhouses had replaced wooden Dutch cottages; church steeples and the masts of cargo ships now towered over wharves and winding thoroughfares. “Here is found Dutch neatness, combined with English taste and architecture,” an admiring immigrant observed. In Manhattan’s streets one saw Germans and Jews and heard English spoken with a Scottish burr or Irish brogue; newcomers mingled with the native sons and daughters of intermarried Dutch, English, and French Protestant families.

4

But the city Washington and his troops entered had become a deeply divided community. For a decade, while the city continued to grow, New Yorkers had grappled with a succession of parliamentary enactments many viewed as economically burdensome, as affronts to their tradition of self-determination within the British Empire, and ultimately as proof of an English plot to force Americans “to wear the yoke of slavery, and suffer it to be riveted about their necks,” as John Holt’s weekly

New York Journal

put it. In response, New Yorkers had taken to the streets in a series of demonstrations, besieging Fort George in protest against the Stamp Act in November 1765, trading blows with angry redcoats at Golden Hill near the East River in January 1770, and dumping tea into the harbor in emulation of Boston’s patriots in April 1774. “What demon of discord blows the coals in that devoted province I know not,” an exasperated William Pitt commented in 1768 after reading a petition denouncing Parliament’s trade policies signed by 240 Manhattan merchants.

5

The Sons of Liberty—the semisecret society of patriots who, from 1765 onwards, organized the street rallies in New York and elsewhere—drew most of their numbers from the craftsmen, seamen, and laborers of the city’s workshops and wharves. The leaders of these “Liberty Boys” were Isaac Sears and Alexander McDougall, privateer captains during the French and Indian War. Sears and McDougall were men on the make, individuals aspiring to wealth and influence. But they were also heirs to a vernacular tradition that posited the common laboring people, the “hewers of wood and drawers of water,” as the true source and ultimate repository of virtue. While artisans and seamen were well aware that men of their station were expected to leave decision making to their “betters,” some Liberty Boys brought to the patriotic movement a willingness to confront men who sported powdered wigs and knee breeches.

6