New York at War (25 page)

Authors: Steven H. Jaffe

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #United States

Although New York State went for Lincoln in 1860, the city delivered a resounding twenty-four-thousand vote majority to his Democratic opponent, Stephen Douglas. As the Southern states seceded from the Union over the winter of 1860–1861 in outrage at Lincoln’s election, Democratic Mayor Fernando Wood proposed that the city declare itself an independent free port in order to sustain friendly trade with the Confederacy. (“I reckon that it will be some time before the front door sets up housekeeping on its own terms,” Lincoln responded.) When the president-elect passed through town on his way to Washington in February, ship riggers on the East River welcomed him by hanging him in effigy from a mast, alongside a banner reading “Abe Lincoln, the Union Breaker.” As Lincoln greeted well-wishers outside the Astor House on lower Broadway, Walt Whitman feared for the Rail Splitter’s life: “Many an assassin’s knife and pistol lurked in hip or breast-pocket there, ready as soon as break and riot came.”

8

The firing on Sumter had—momentarily—quelled the enmity toward the president, bringing New York’s Southern-oriented businessmen and Democrats into patriotic alignment with Lincoln Republicans. Merchants who had previously argued for appeasement to keep the South from seceding now pressed for a swift war to restore the Union. A short war would reestablish the status quo without disrupting slavery in the Southern states, pleasing Democrats. But bipartisan harmony remained superficial, for it compelled the city’s Republican minority to work with a Democratic majority whose values and many of whose leaders they despised. For decades, men who disliked the Democratic Party’s pro-Southern policies, embrace of workers and Catholic immigrants, and local reputation for corruption—usually native-born Protestant merchants, professionals, and artisans of middling or elite status—had flocked into opposition parties, the latest version of which was the Republicans.

Lincoln’s party was opposed to the expansion of slavery, but only a minority of Republicans in New York were radicals bent on abolishing the South’s “peculiar institution.” A typical Republican was George Templeton Strong, who joined the local party organization in 1856. Proud scion of a family with deep roots in colonial New York and New England, owner of an elegant Gramercy Park townhouse, Strong embodied the conservatism of New York’s Protestant elite. He joined the Republicans in outrage at what he perceived as “the reckless, insolent brutality of our Southern aristocrats.” Of far less concern to Strong were the rights of black people, whom he persistently described as “niggers” in his diary, or the arguments of abolitionists, “who would sacrifice the union to their own one idea.” By 1859, however, disgusted by what he viewed as Southern domination of the federal government, Strong was convinced that “the growing, vigorous North must sooner or later assert its right to equality with the stagnant, semi-barbarous South. . . . It must come.”

9

The only group who disgusted Strong as much as did Southern aristocrats was the city’s mass of poor Irish Catholics, “those infatuated, pig-headed Celts.” Disdain and fear of the Irish were shared by many native-born Republicans. “The most miserable and ignorant of other countries are shot into New York like rubbish,” the Republican

Harper’s Weekly

editorialized during the war. “ . . . They are led by the demagogues who depend upon their votes for success.” These tensions, pitting the Republican elite against the Democratic masses, embodied fissures of class, ethnicity, and religion that had permeated the city’s political and social life by the onset of war.

10

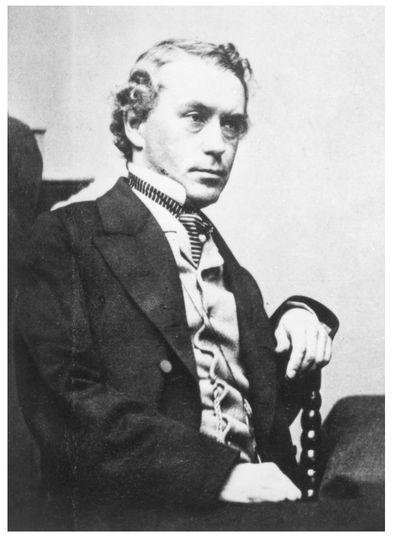

George Templeton Strong, patrician lawyer, diarist, and participant in many of New York’s key Civil War events. Illustration from

The Diary of George Templeton Strong,

71367. COLLECTION OF THE NEW-YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY.

The majority of New York’s Irish emigrants lived in a very different city from that inhabited by Strong. New York had an Irish Catholic community by the 1820s; tens of thousands more, driven across the Atlantic by the potato famine of the 1840s and 1850s, landed in New York without money to take them farther. By 1855, one-quarter of the city’s population—two hundred thousand people—had been born in Ireland. Most were crammed into festering slums on the east side of lower Manhattan and into shanties and tenements on the city’s northern outskirts, often only a stone’s throw from blocks of new row houses built for affluent families. The Irish performed the city’s lowest-paying wage work, toiling as day laborers, longshoremen, drivers, laundresses, seamstresses, and servants. By the 1840s, bloody riots between gangs of Irish Catholics and native Protestants—and by both groups against constables and state militia—were commonplace. In the worst slums, a reform group would report in 1865, tens of thousands of immigrants were “literally submerged in filth and half stifled in an atmosphere charged with all the elements of death.” The mortality rate in slum areas was more than twice that in the townhouses of the upper-middle-class Murray Hill district.

11

While other Europeans were often welcomed into the social fabric of New York (German emigrants, for instance, the era’s other large group of newcomers, gained a reputation for being “respectable” and steady), the Irish were stereotyped as primitive and brutish for their boisterous drinking culture, the crime and violence that beset some of their neighborhoods, and the Catholicism that led them to defy the anglophile Protestant elite. They embraced the Democratic Party, the only powerful institution in the city (apart from the growing Catholic Church) that welcomed them with open arms. They also shared in a brotherhood that exalted them for their white skin and made them equals at the ballot box with New York’s richest bankers and merchants. Republicans, thundered Democratic journalist James Brooks, were bent on “the negation of the white race and the elevation of the negro.” Such rhetoric posited the Irish as far superior to the African Americans with whom they competed for the city’s worst jobs and housing, even superior to the Republicans who lived in mansions. Thousands of New York Irishmen enlisted and marched off to war in 1861, passionate in their patriotism and proud to affirm their American citizenship. But the war they entered was emphatically one to restore the Union, not to free slaves.

12

While New York’s Irish population was growing, the city’s black community was a small but visible presence, its members numbering under 13,000 in 1860. New York State had only fully abolished slavery in 1827, and a rigid racial hierarchy continued to dictate the terms of daily life in the city. A small middle class of clergymen and tradesmen provided leadership, but the majority toiled in poverty as laborers, petty vendors, waiters, servants, and laundresses. Increasingly they had been displaced from many jobs by the influx of poor Irish. Although not isolated in a distinct ghetto, and in some districts intermingling and even intermarrying with their Irish neighbors, most lived in scattered, segregated pockets—an all-black tenement here, a row of shanties there.

While some elite white New Yorkers sympathized with the plight of their black fellow Protestants, most shunned meaningful contact. “I have an antipathy to Negroes physically and don’t like them near me,” Maria Lydig Daly confided to her diary a few days after Bull Run. Streetcars and steamboat lines were racially segregated, and any number of businesses were off limits to black consumers. New York’s state constitution placed prohibitively high property qualifications on black voters; the electorate rejected the elimination of this racist disenfranchisement in 1860, nowhere more decisively than at the Manhattan polls. Wherever they looked, New York’s blacks encountered a city that denied them anything resembling equal rights and opportunities. The physician James McCune Smith, one of the city’s most distinguished black residents, characterized such racism as the “damning thralldom that grinds to dust the colored inhabitants.”

13

In the face of such discouragement, New York’s black men and women fought back, plunging ardently into the antislavery movement and into efforts to improve their own lot. The city was home to black congregations like Reverend H. H. Garnet’s Shiloh Presbyterian Church on Prince Street, a bastion of militant abolitionism and race pride. Black abolitionists Albro and Mary Lyons turned their waterfront boardinghouse into a station for hundreds of fugitives fleeing the South along the Underground Railroad. When James Hamlet, a fugitive slave, was seized on the street and spirited back to Maryland under the terms of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, abolitionists raised $800 to buy his freedom, and a triumphant, largely African American crowd welcomed him home to a reception in City Hall Park.

14

Black New Yorkers were aided in their struggle for equality by a small group of white abolitionists. John Street in lower Manhattan was the headquarters of the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, funded by the brothers and wealthy dry goods importers Lewis and Arthur Tappan. So enraged were Southerners by the antislavery propaganda issuing from New York that Louisianans put a $50,000 price tag on Arthur Tappan’s head. Radicals also had to stand the storm aroused in New York by their message of immediate abolition. In 1834, a white mob had rampaged to prevent an interracial meeting of abolitionists in a downtown chapel, and the violence escalated into several days of attacks on blacks and the homes and stores of white antislavery activists.

15

The emancipationists, black and white, persevered. With war now upon the nation, they persisted in viewing New York as a center for something more sweeping, more transcendent than a mere conflict to restore the Union. At the same time, they were as aware as anyone that the tensions dividing their city—separating Republicans from Democrats, rich from poor, natives from immigrants, Protestants from Catholics, blacks from whites—represented a tinderbox the war might ignite.

While the war’s outbreak did little to quell the city’s underlying frictions, it invigorated the city’s economy. New York rapidly became the money city of the Northern war effort. After the Bull Run defeat, Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase borrowed $150 million from Wall Street bankers to pay the war’s mounting bills. Over the next four years, New York financiers underwrote a dizzying expansion of the federal government’s budget, enriching themselves in the process. A healthy portion of the funds loaned to the government, moreover, came back to the city in the form of military contracts. New York’s merchants and manufacturers were able to think and deal on a scale that suited an institution like the US Army, which expanded almost overnight from 16,000 to over half a million men. The army’s Department of the East, headquartered on Bleecker Street, became the point from which federal funds were dispensed into Manhattan pockets and bank accounts. Thousands of workers toiled in foundries and shipyards lining the Hudson and East River waterfronts, churning out huge engines and boilers for the navy. Raw materials and finished goods—bread, pork, medicines, uniforms, shoes, blankets, gun carriages—continually flowed out the Union’s “front door” to the troops in the field. New York was awash in war money. “Look at her seated between two noble rivers forested with masts,” the

Journal of Commerce

boasted after half a year of war. “She has learned how to prosper without the South.”

16

War prosperity, however, quickly revealed another side, one that inflamed rather than reduced the city’s social tensions. Wages for workers rose, but not as fast as prices did. The cost of coal, flour, potatoes, beef, and milk doubled in the face of shortages and an inflationary paper currency, eroding family budgets. Skilled machinists could at least negotiate, and sometimes strike successfully, for wage hikes. Less skilled workers were not so fortunate. Thousands of the city’s women and girls, a

New York Times

reporter charged in 1864, “whose husbands, fathers, and brothers have fallen on the battle field, are making army shirts at six cents apiece.” To load military transports, employers replaced striking Irish longshoremen with prisoners of war (mostly Union army deserters), German immigrants, and, to the bitter fury of strikers in the spring of 1863, free blacks.

17

In truth, the war increasingly came home to the families of poorer enlistees in the form of calamity: a husband killed, a father disabled—a wage earner who would never again help to support his family. The city government provided benefits to the families of soldiers away at the front and to war widows and orphans, but the funds did not reach everyone, and the money often arrived late, prompting public protests by working wives and mothers. “You have got me men into the soldiers, and now you have to keep us from starving,” a woman implored officials during a rally in Tompkins Square late in 1862.

18