New York at War (29 page)

Authors: Steven H. Jaffe

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #United States

The sense of helplessness that the Draft Riot induced in many affluent New Yorkers gave way to a redoubled commitment. The US Sanitary Commission, a quasi-public body founded by a handful of Manhattan businessmen, professionals, and doctors, worked with the federal government to improve health conditions for Union troops in the field and in military hospitals. From its executive headquarters at 823 Broadway, the commission controlled fleets of steamers, barges, and wagons; dispatched tons of medicine and supplies; hired doctors, orderlies, and nurses to supplement those of the army’s overburdened Medical Bureau; and by early 1865, supervised over five hundred agents in the field who sought to monitor and remedy dismal conditions in the hospitals. New York society women, deprived of careers by prevailing gender roles, seized the opportunity to toil actively in a public cause. Some trained as volunteer nurses or doctor’s assistants and were even paid for their work. Although often resented by male professionals, many served unflinchingly under daunting conditions. Maria Lydig Daly’s unmarried friend Harriet Whetten nursed sick and wounded soldiers in Virginia. “She looked very happy,” Daly observed when Whetten returned to New York in May 1862. “She has been longing for some active employment and would like to have gone soldiering, I think, long ago.”

55

While the wounds inflicted by the Draft Riot lingered, on the surface New York resumed its daily round of getting and spending, of feverish bustle and lavish consumption, especially in its upper social echelons. In early 1864, as Sherman had prepared his troops for the drive toward Atlanta, and Grant had primed his for a campaign against Richmond, New York still seemed able to insulate itself from the war’s destruction, a fact that infuriated Southerners who learned of continued Northern tranquility through newspaper accounts and correspondence. Disappointed in their expectation that the Draft Riot would be followed by escalating Northern turmoil, Confederates decided to bring the war to New York themselves.

The prospect of a combined attack from inside and outside the city played on the minds of many New Yorkers. Republicans in particular refused to believe that the Draft Riot had not represented some deep-laid conspiracy between Confederate agents and local Copperheads. The

New York Times

went so far as to label the draft rioters “the left wing of Lee’s army.” In truth, the city had become a sanctuary for refugees from Southern war zones, estimated as numbering from ten thousand to fifty thousand. Some had come north to be near husbands or relatives who were among the hundreds of prisoners of war being held in Fort Lafayette in the Narrows and elsewhere around the harbor. “The city is literally swarming with rebel adventurers of an irresponsible and dangerous class,” the

Times

warned. Many assumed that spies were conveying news of local troop and ship movements to Richmond. Major General John Dix, commander of the Department of the East, ordered all Southerners in the city to register with the army or else be considered “spies or emissaries of the insurgent authorities in Richmond,” but only a few hundred bothered to show up at the Department’s Bleecker Street headquarters to give their names, residences, and vital statistics. While Republicans remained enraged at Northern Peace Democrats, no evidence ever proved that Southern agents or New York Copperheads premeditated the Draft Riot (although local Democratic politicians clearly had tried to spark a more focused resistance to the draft itself). Such allegations nevertheless allowed Strong and others to overlook the grinding poverty, anti-Irish prejudice, and class discrimination that had helped fuel the riot.

56

When it did come, in the fall of 1864, the Confederate plot against New York would mainly be the work of outsiders. During the last year of the war, a cadre of Southern agents led by a Mississippian, Jacob Thompson, used Toronto, Canada, as a base for a series of audacious assaults against the North. Most of their schemes, such as an attempt to get Midwestern Copperheads to rise in armed insurrection, failed miserably. But in September, when Union general Philip Sheridan’s troops ravaged the farms of the Shenandoah Valley, Thompson’s operatives meditated revenge. One of them, Dr. Luke Blackburn, proposed poisoning New York City’s water supply in the Croton Reservoir on Fifth Avenue. Instead, Thompson’s group settled on an idea broached in the Richmond

Whig

, which in October declared, “New York is worth twenty Richmonds. . . . They chose to substitute the torch for the sword. We may so use their own weapon as to make them repent, literally in sackcloth and ashes, that they ever adopted it.”

57

Under the Confederate plan, a group of saboteurs would infiltrate New York from Toronto, and on Election Day, November 8, they would set fires and foment an uprising by Copperheads, who would turn the city against the Union war effort. On October 26, eight men, including two Kentuckians, Colonel Robert Martin and Lieutenant John Headley, and a Louisianan, Captain Robert Cobb Kennedy, boarded a train in Toronto bound for New York. Fearing trouble on Election Day, however, Secretary of War Stanton made sure that General Benjamin Butler and 3,500 Union troops were present. With Butler’s troops circling Manhattan on ferries and gunboats, New Yorkers registered their protest with ballots rather than weapons, giving Lincoln’s Democratic challenger, George McClellan, a thirty-seven-thousand-vote lead in the city. The presence of troops daunted the Confederate agents. They bided their time, meeting in boardinghouses and hotel rooms, until Butler’s soldiers left on November 15.

58

On the evening of November 25, New Yorkers who ordinarily ignored the tolling of the bell in the City Hall cupola took heed as the doleful sound echoed from fire towers and church steeples throughout the city. Dark smoke poured forth from one and then another of the city’s hotels—from the St. James at Broadway and Twenty-Sixth Street, the Fifth Avenue, the Astor House, and nine others. As word spread through the Winter Garden Theatre that the Lafarge House next door was on fire, one theatergoer noted that “the wildest confusion, amounting to a panic, pervaded the vast audience.” During the night, blazes also erupted on a barge along the Hudson River, in a West Side lumberyard, and in P. T. Barnum’s famous museum on lower Broadway.

59

Pedestrians, hotel guests, and streetcar riders quickly realized the fires were not accidents. As firemen and police converged on the various hotels and put out the flames, they congratulated themselves on their luck: the arsonists had saturated furniture and drapery in “greek fire”—a spontaneously combustible mixture of phosphorus in a bi-sulfide of carbon—but had closed room windows and doors when they fled, depriving the flames of oxygen. Most of the fires merely smoldered and were easily quenched. No one was killed or seriously hurt in the fires, although the St. Nicholas Hotel sustained $10,000 in damage. But the newspapers warned of what might have been: Manhattan would be “in flames at this moment,” the

Tribune

averred, had the plotters properly ignited the fires. Meanwhile, the arsonists eluded a police dragnet around the Hudson River Railroad terminal at Thirtieth Street and Tenth Avenue, boarded a train for Albany, and were back in Toronto on November 28.

60

City and federal officials looked northward, well aware from the reports of informers and Union spies that Toronto had become a Confederate base. The Metropolitan Police dispatched six detectives to Detroit and Toronto, where leads paid off. When Robert Cobb Kennedy tried to slip into Detroit on his way back to the Confederacy in late December, two detectives were waiting for him. “These are badges of honor!” Kennedy shouted to fellow passengers on a New York–bound train as he brandished his handcuffs at them. “I am a Southern gentleman!”

61

A military commission appointed by Major General Dix convicted Kennedy as an enemy spy. At the last moment, as he faced the hangman’s noose, Kennedy penned a confession: “We wanted to let the people of the North understand . . . that they can’t be rolling in wealth & comfort, while we at the South are bearing all the hardship & privations. . . . We desired to destroy property, not the lives of women & children although that would of course have followed in its train.” On the afternoon of March 25, 1865, Robert Cobb Kennedy was hanged in the courtyard of Fort Lafayette, the only man ever convicted in the arson plot and the last Confederate soldier executed by the Union during the Civil War. “Think of me as if I had fallen in battle,” he wrote in his last letter to his mother.

62

The question of Copperhead complicity in the plot remained a murky one. The police arrested and then released a number of Confederate sympathizers, including Gus McDonald, a Broadway piano dealer who had stored the arsonists’ luggage. A mysterious Washington Place chemist who allegedly provided the agents with “greek fire” was never apprehended. Decades later, Kennedy’s fellow conspirator John Headley, who had become Kentucky’s secretary of state, charged that John McMaster, one of the city’s bitterest anti-Lincoln newspaper editors, had promised the plotters an uprising by twenty thousand Manhattan sympathizers to coincide with the fires. Although impossible to disprove (McMaster was long dead), Headley’s allegations against him and other New York Democrats seem implausible, and not only because Headley had various ulterior motives for making his claims. Why, after all, would New Yorkers—even ardent friends of the South—want their homes and businesses to burn down?

In the end, the plot had served to “give the people a scare,” in Kennedy’s words, but it smacked more of Ruffin’s and Mallory’s fantasies than of any realistic strategy for Southern independence. True, if the fires had ignited and spread, New Yorkers might have had a formidable act of terrorism to contend with. But the fires merely sputtered, and for a city that sixteen months earlier had endured what the

Times

called “the Reign of the Rabble,” the arson plot seemed paltry, the last gasp of a dying cause.

63

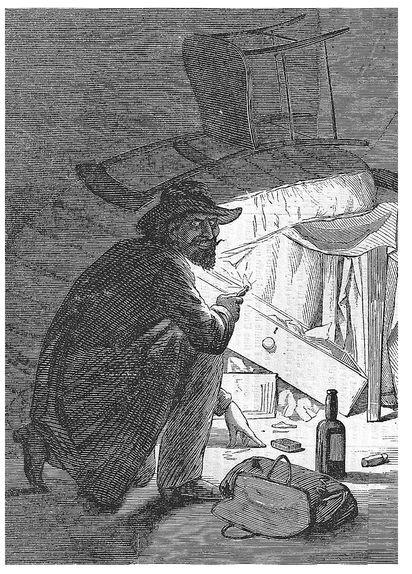

A diabolical Confederate agent prepares to torch a Manhattan hotel room, as pictured in

Harper’s Weekly

. Detail from engraving by unidentified artist,

Adjoining Rooms in a Hotel in New York,

in

Harper’s Weekly,

December 17, 1864. AUTHOR’S COLLECTION.

“Never before did I hear cheering that came straight from the heart,” George Templeton Strong wrote of the scene in Wall Street on April 3, 1865, as news of the Union army’s entry into Richmond spread through the city. “Men embraced and hugged each other,

kissed

each other, retreated into doorways to dry their eyes and came out again to flourish their hats and hurrah. There will be many sore throats in New York tomorrow.” Seven days later, the joyous news of Lee’s surrender to Grant arrived; only a rainstorm kept the city from an uproarious celebration outdoors. But then, on the morning of April 15, New Yorkers awoke to the news of Lincoln’s assassination. Throughout the war years, few New Yorkers had responded to the president with unbridled enthusiasm. War Democrats like Maria Lydig Daly had derided him as “Uncle Ape . . . a clever hypocrite,” and even Strong had considered Lincoln “far below the first grade.” Now, in the wake of the assassination, Strong changed his view. “I am stunned, as by a fearsome personal calamity . . . ,” he wrote. “We shall appreciate him at last.”

64

In many ways, New Yorkers put the war behind them quickly, finding new ways to make money after the war contracts dried up. Never again would cotton loom so large in the city’s economy; businessmen and investors looked elsewhere for profit, to railroad securities, industrial expansion, and maritime trade. Workmen largely eschewed rioting for a growing trade union movement—albeit one that sustained the spirit of the Draft Riot by rigidly excluding African Americans. The city’s battles were now fought in newspaper columns, courtrooms, and polling places as reformers sought to dethrone “Boss” Tweed and to limit the power of the Tammany voters Strong called “ignorant emigrant

gorillas

.” New Yorkers felt themselves to be living in a new and different era. Looking over a scrapbook of five-year-old newspaper clippings in May 1865, Strong observed that “it seemed like reading the records of some remote age and of a people wholly unlike our own.”

65

Yet the war’s legacies—and its wounds—lingered. Racism remained the common currency of the New York Democrats, and the war was hardly over before the city’s Democratic leaders resumed their overtly cordial ties with the South’s former slaveholders. Both upstate and downstate, New York’s electorate voted down a state measure that would have given black men equal suffrage rights in 1869; that right was only obtained through the federal Fifteenth Amendment in 1870. In the presidential election that spelled the end to Reconstruction in 1877, Manhattan lawyer Samuel Tilden, the Democratic nominee, repeatedly avowed the cause of white supremacy and black subservience. Many of the city’s Republicans also turned their backs on African Americans, weary of the issues that had torn the nation and city apart. By 1874, George Templeton Strong, who a decade earlier had stood in Union Square stirred by the sight of black soldiers, found little to choose between New York’s Democratic “Celtocracy” and those reconstructed Southern states allegedly dominated by a “Niggerocracy.”

66