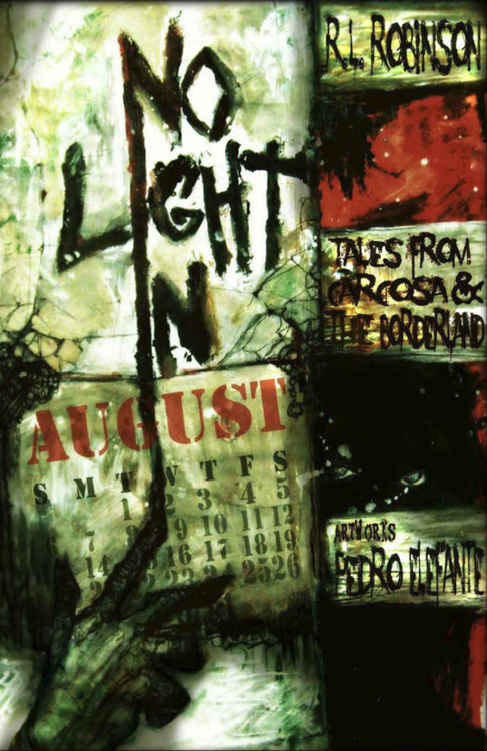

No Light in August: Tales From Carcosa & the Borderland (Digital Horror Fiction Author Collection)

Authors: Digital Fiction

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Genre Fiction, #Horror, #Short Stories & Anthologies, #Short Stories, #British, #United States, #Single Authors

NO

LIGHT

IN

AUGUST

Tales

from Carcosa and the Borderland

By

R.L. Robinson

NO

LIGHT

IN

AUGUST

Tales

from Carcosa and the Borderland

By

R.L. Robinson

Collection

copyright © 2016 Digital Fiction Publishing Corp.

Stories

copyright © 2016 R.L. Robinson

Illustrations

copyright © 2016 Pedro Elefante

Edited

by: Christine Clukey Reece

All

rights reserved.

ISBN-13

(paperback): 978-1-927598-26-9

ISBN-13

(e-book): 978-1-927598-27-6

The

collection would not be possible without the help and contribution of Karen

Gubbins and Robert Cano.

Karen is

perhaps the best beta reader I’ve ever encountered. Her help and critical eye

proved invaluable in the creation of this collection.

Robert

Cano is one of the best writers and readers it has been my privilege to meet

and talk with. His support in this work has been invaluable.

Special

mention must also go to Christine Clukey Reece, an editor and friend who is

second to none.

My thanks

to you all.

To Andrew, Louise, Natalie, Levi, Andy (Welshy), Andy,

Dave, Maria, Iain and Nick. To Polly, Steven, Carmen, Jenny, Ciaran, Peter,

Ewan, Christopher, Tom and Michael and Martina. My friends, who remind me there

are good things in this world.

To my mother and father; although separated, both of

you were there for me when I did well and when I messed up.

I’ll never forget that and I can never repay it.

As I write

this introduction, the collection isn’t yet finished, but I write it for the

day it will be.

Growing up

I read a lot and nothing enticed my imagination more than horror, the

supernatural and the weird; hence this collection.

The

stories here span time, space and worlds. Carcosa and the King in Yellow are

with us everywhere and every

when

. To me they exist across all time and

space, have always existed and always will. They represent something elemental

and primal; the place where all is possible, even if you don’t want it to be

so.

It exists

as a reflection of us; the place where all devils come from. It is a hell where

the devils exist not

for

us, but

because

of us.

This is

easily the darkest work I’ve attempted to write and the decision to have it

illustrated was always foremost in my mind. To me illustrated collections have

a special, nostalgic significance.

Not all of

the stories here will appeal to everyone; perhaps the artwork will be the best

thing about it for some readers.

Nonetheless,

I invite you to take a trip through the borderland to Carcosa and spend some

time with the King’s subjects. Who knows…you might find you belong there with

the rest of us after all.

-

Vienna, July 2014

Hanging

from the cart’s iron bars, or else secure on top, were all manner of weird

things.

Whent

looked up, startled from his cleaning work as three men banged the door open and

strode into the tap room.

“My name

is Haran,” one said and gestured to the two behind him. “This is Foss and Iayn.

We need

ale and food and our horses stabled and fed for the night.”

“Hurry up

there,” Iayn said, sliding a chair noisily across the boards. “We’ve ridden

hard.” “Of course, of course,” Whent said hurriedly and ducked around the bar.

He filled three

tankards,

tipping the keg forward to drain what was left. “Where have you come from,

sirs?”

He placed

a tankard in front of each. Friendly chat was often the best way to deal with

men carrying good steel and the potential for violence.

“North of

here,” said Foss. “We sold our swords to Marshal Cray.” “You were hunting the

mutineers from the River Fort?”

“We were,”

said Haran, taking a mouthful of ale. “Found some, but the rest have turned

brigand and scattered across the country.”

“We heard,

though we’ve not seen any sign of them.” Nor did Whent think the town would

stand much of a chance if they did. A merchant passing through the day before

said he’d come across a village all burned out and with the townsfolk crucified

along their makeshift palisade.

“Damn

fools,” Iayn put in. “But then, the River Fort ain’t the best place to end up

soldiering.

Fuck all

there, for one thing.”

“Like as

not to break a man’s spirit and make him think about other uses his skills

might be put to,” said Foss.

Whent

looked the three men over before leaving for the kitchen to see what he could

scrounge up from the pantry. As he was raking the shelves for what he hoped the

three would find a satisfying meal, he thought about what his father had said

and what passed through the village days before.

Here in

the north, things are older

, he’d

said. Whent was just a boy then, not much older than four or five, but he

remembered it.

The

towns, the stories, and the memories all speak to an elder time, when people

feared what lurked in the night

. Aye,

that was true enough, and Whent knew many still did — and perhaps they were not

wrong to never stop.

Things

do still crawl near the frost fens because they, like the people, remember they

are supposed to.

Perhaps

they could explain it — they seemed like men of the world, and doubtless men

who sold their edged steel had seen and done much. Perhaps they would laugh at

his superstition and take him for a northern bumpkin who jumped at shadows.

Either

way, it would provide some entertainment and perhaps make up for any

disappointment they might feel about his cooking.

“Something

on your mind, innkeep?” Iayn asked as Whent lingered close to hand after

handing the plates over.

“Well,

sirs…it’s maybe nothing, but I have a story to tell you…thought you might have

heard something about it,” he said as he twisted his apron between his hands.

“Might be nothing, but it was right strange, so it was.”

Haran

stared into his tankard as if expecting more ale to mysteriously appear. “A lot

of strange things happen up here, but why not give us a refill and tell us,” he

said, picking up a sausage from his plate. “Distractions are hard to find.”

Whent did

as he was bid, and he poured a half for himself while he was at it. Pulling a

chair up, he took a drink to clear his throat before beginning.

“It was

about a fortnight ago; you see…”

Whent

could say nothing much happens in town. The odd passing wagon or rider, but

little else besides; about all the most regular visitors came from the farms

roundabout.

The mutiny

to come at the River Fort was only a rumor, talk of grumblings among the

garrison carried back to town by the men who supplied the soldiers’ food. It

wasn’t the first time they’d heard such things, so they paid them no mind.

Then one

day, a wagon man returning south told them there was a strange procession

coming down the road.

“They’ve

put in at the garrison,” he said. “Like as not, it might quiet ‘em down and set

‘em at

ease.”

“What kind

of procession?” someone asked.

“Looks

like a carnival, if ever I saw one.”

“Where’d

it come from?” Everyone knew there was precious little beyond the River Fort,

save the mountains and the savages who lived there.

“Who

knows?” he responded, gobbing some of his chew into the dust as he climbed into

the driver’s seat. “But it should be here by tomorrow.” He flashed a toothy

grin. “Strangest fuckin’ sight I ever laid eyes on.”

As the

wagon man said, they did indeed arrive in town the next day. They were heard

before they were seen — a jangle and creaking of wheels loud enough to carry

ahead of the procession.

A

scattering of townsfolk made their way into the thoroughfare to watch the

approach and were joined later by most others. When the carnival drew close

enough, it let out a blast of trumpets, together with a rhythmic drumbeat

underscoring the blaring horns.

The line

it formed wasn’t big, but it wasn’t small either. A thin man rode at its head

on a great horse, most likely bred for war.

He wore a

cloak that looked to have been ripped up and stitched back together, only with

different-colored cloth mending the tears. Red seemed to be his favorite choice

on that score, and as he rode into town, Whent saw his face was covered in dark

ink.

None of

the shapes and patterns made the least bit of sense; it was all swirls and

whorls.

Underneath

the ink, the man’s skin was an angry red, especially around his eyes.

Six men

trudged behind the rider; tall and wiry, they had a wolfish look about them and

seemed to stare hungrily at the crowd. But they weren’t the strangest sight,

not by a long way.

Pulled by

more men, each in harness, the center of the parade was taken up by a huge

cart. Though cart didn’t quite describe it — it was more like a wooden platform

on wheels, enclosed by iron bars. There was no roof, so the bars wobbled about

as it moved along.

Men and

woman capered around it, wearing grim parodies of carnival costume. Jesters in

black, with necklaces of bone trinkets dangling about them; dancers wearing

almost nothing, save for pelts.

The wagon

man was right. It was a strange sight.

A fire

breather tossed a pair of small birds in front of him and burned them from the

sky, the flames licking over the heads of the audience. He produced the same

birds again, seemingly from thin air.

Hanging

from the cart’s iron bars, or else secure on top, were all manner of weird

things.

Masks and

shoes, a pair of woman’s gloves, and the bleached ribcage of what could’ve been

a child for its size and shape.

There were

other bones too, all mismatched around it to make a bizarre and grotesque

skeleton. Someone had fixed a pair of rotting wings, pulled from

some great bird, to its back. A dog, or maybe wolf’s, head was transfixed onto

the bar above it all. Its tongue hung between its lips, frozen in something

that might have been a snarl.

“Is that

it?” asked Haran, now on his third ale.

“More or

less, but that ain’t the strangest thing ‘bout it.”

Iayn and

Foss exchanged a look. “Go on, then,” Foss offered.

“Well,

they performed somethin’, though I’d not claim to know what…seemed like a bit

of theatre and a bit of magic. The usual stuff; dancing, juggling, fire eating,

and the like…but it was all darker somehow.”

“I don’t see

where this is going,” said Iayn. “Well, it’s hard to put into words.”

“Then

don’t try,” put in Haran. “Just say whatever comes and don’t mind if it’s right

sounding.” The story and the ale had lulled them, but it looked like it

wouldn’t hold.

“They camped

outside of town for a night and moved on. They never took any payment or food

or nothin’, just left.”

That was

strange, Iayn thought. In his experience, performers of most stripes would have

the gold out of your teeth given half a chance. He saw that Foss and Haran

agreed.

“And

there’s been a strangeness in the air ever since,” Whent said, spreading his

arms at the empty taproom. “I’d be full on any normal night. People’s stayin’

away, and they’re snappin’ at each other more ‘an usual. Why, last night, Malick

— he’s the smith — he beat his wife half to death for no good reason.”

“Are you

saying they worked a spell?” asked Iayn.

“I’m a

god-fearin’ man, so I’d rather not say.” Whent hummed and hawed about

mentioning the tracks, then decided he probably should.

“What sort

of tracks?” Foss leaned back and belched, dumping his empty tankard on the table.

“Weren’t

like none I’ve seen…there weren’t no shape to them, but they were too

regular-like

to be

anythin’ else.” Whent rose and went to the mantle over the fire. He returned

with a bottle of brandy and poured a tot into each of their empty tankards.

“There was a mark on Malick’s door, near more of ‘em.” He traced a vague shape

in the air. “Made me think of the ink on the thin man.”

“If we see

them, we’ll give them a wide berth,” Iayn reassured him.

Whent

wanted to say that wasn’t why he was telling them about the carnival, but the

drink only served to muddle his head more than he’d intended.

They rode

out the next morning, heading south first before turning north again. “You were

right,” Foss said.

Iayn

didn’t reply, just kept looking straight ahead. “Sad to hear you doubted me.”

“Can’t blame a man for asking questions.”

“There’s

truth to that, I suppose.”

“You think

we should’ve stayed back there?” asked Haran.

“No

point,” Iayn said as he looked over to where the town was, though it was now

hidden behind some hills. “Won’t be anything left of it before too long.”

The other

two didn’t question Iayn. Once they might have, but after what they’d seen

around the River Fort and surrounds, the impetus to do so was gone. It still

kept them up some nights, and none of them could be said to be soft about such

things.

Marshal

Cray was still further north with the bulk of the regulars and free swords.

Most of the mutineers were run to ground now, but not all. Not the leader, who

survivors had identified as a thin, tattooed man — a deserter with no name. The

fact that no one had stopped him spoke to mutiny over a single night, and the

countryside had been burning before anyone realized it.

“What do

you reckon about this rabble he’s picked up?” Haran asked.

“Hard to

say, but I doubt they’re from the garrison. No women there, for one thing.”

“Hill

people?”

“Or fen

folk, maybe.”

Whatever

the answer, they had the trail; a group that big left one that a blind man

could follow. It just didn’t make sense why they were turning north again.

The land

became more hilly as they rode into the far north once again, returning to

places each would rather forget. The ground alternated between rolling hills

and deep valleys where the frost fens started. Their horses kicked up clods of

damp earth as they went, forced to wander into the fens because the trail led

there.

“Why

wouldn’t they take the high ground?” Foss guided his horse through tricky

water, tugging the reins to keep the animal steady. “Firmer going, for one.”

“Trying to

reason out what mad folk do leads you down the same road,” said Haran. “You’d

know all about that, wouldn’t you?”

“There’s

more than just madness about these people,” Iayn put in. There was magic in the

world, of course. Neither good nor bad, it depended on the person who used it.

They’d just never seen it for themselves.

Perhaps

they were starting to believe.

The deeper

they went into the fens, the more the land began to age. It felt as if the

places they rode through might not have been disturbed for an age, save for the

passing of the troupe they followed.

Few sane

men would travel so far. The fen folk were not known for their hospitality.

“How the

fuck could they get a wagon or whatever it was through this?” Haran’s horse was

ready to drop; they’d pushed too hard; it was impossible to coax more out the

animals.

“It

doesn’t matter, we’re close.” Foss pointed ahead.

Mist rose

from the fen, but a shape resolved itself, seeming to grow out of the cloud. It

was a figure, upright and arms flung wide apart. Pulling ahead, Foss saw it was

not one figure, but several; or rather, the pieces of several. Crudely stitched

together, the collection was lashed to a crude cross.