North Yorkshire Folk Tales (14 page)

Read North Yorkshire Folk Tales Online

Authors: Ingrid Barton

‘Well,’ said the abbot, ‘we can’t begrudge a loaf of bread to a starving man! One and a half loaves will have to be sufficient for us lucky people who are not yet starving.’

The porter took one of the precious loaves to the traveller, who blessed the monks fervently as he at last began to fill his empty belly.

There were only a few mouthfuls of bread for each of the monks who had been working and nothing at all for those who had not, but filled with the happiness of having helped a stranger in trouble, they did not complain.

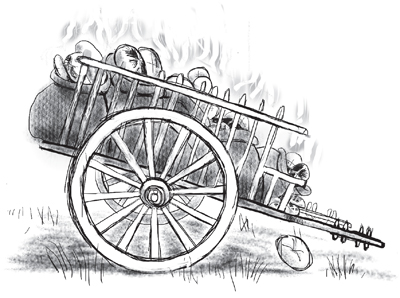

A few hours later, there was another knock on the door and the porter opened it to find two men with a large cart standing outside. From the cart came the intoxicating smell of fresh bread.

‘Sir Porter,’ said one of the men, ‘the Lord of Knaresborough Castle, Sir Eustace Fitzhugh, hearing that you are short of food, has sent you this cartload of bread.’

The monks all rejoiced and praised God, believing that He had seen their plight.

It was from this time that Fountains Abbey, as it became known, began to flourish until at last its fame spread throughout the region and it became rich and powerful. The twelve brave founders were always honoured, but whether those that followed in the years after them, as the abbey grew ever richer, were as holy or as ascetic is less certain.

EMER

W

ATER

Dales

Raydale at the head of Wensleydale is a place of kelds (springs). Their wild waters, flowing from the mysterious limestone caverns that lie beneath Wither Fell, Addlebrough and Stalling Busk, break out into many little becks and flow into Semer Water, one of the few lakes in the Dales. There are waterfalls too, sparkling in the sunlight, white in the rain showers that rush up the valley. It is a hard place in winter, though, when the roads are icy and the tracks over the hill are as treacherous as the peat bogs they skirt.

On one such winter’s day, an old beggar was slowly making his way towards the entrance of the prosperous town that lay in Raydale valley. Where he had come from, why he was travelling, even what his name was, is not told in the story. Perhaps he himself had forgotten these things in a hard life. Or perhaps he was not what he seemed …

He stopped before the first small cottage he came to and approached the door. Before he had even raised his hand to knock, however, it was opened by a woman holding a broom in her hand. ‘What do you want?’ she asked suspiciously, taking in his way-worn clothes and rag-covered feet.

‘A drink of water, missus?’ the beggar asked humbly.

‘What’s wrong with beck water?’ she demanded. ‘Get along with you!’ She slammed the door before the beggar had time to tell her that the becks were all frozen over.

Slowly he moved on up the main street.

The next cottage he stopped at had a fine first storey that overhung the street. A tailor was sitting cross-legged on a table in the big sunlit window of the upstairs parlour. The old man looked up and the tailor looked down. Then the tailor leant forwards and opened the window.

‘I’ve nowt for beggars,’ he shouted. ‘Go away and stop cluttering up my street!’

‘A little water, maister? A crust of bread?’

‘Mary!’ shouted the tailor angrily. ‘Water for the beggar!’

A little dormer window opened above him and a grinning maid emptied a chamber pot into the street, missing the old man by a whisker. The tailor laughed uproariously and slammed his window shut.

Shaking his head sadly, the old man continued up the street. Soon he came to a large house with fine carving on its timbers – a prosperous butcher’s house. Surely, such a well-off man could spare something for a beggar.

The beggar knew better than to knock at the front door. He went around to the kitchen at the back. A smart lad opened the door and peered out.

‘Can you spare awt to eat or drink, young sir?’

The lad threw his eyes up to heaven. ‘What sort of gowk are you? Hasn’t anyone told you? Maister can’t bear your sort. Get going before he finds you here!’

And so it went all the way through the town. In one house the cook pretended that the old man must belong to a gang of thieves come to spy on the place; in another the man of the house, tankard in hand, lectured him on working hard instead of being a layabout. ‘The undeserving poor are leeches sucking the wealth out of this country!’ he said.

In yet another, where a fat family were about to begin an enormous dinner, he was told that charity begins at home. ‘If we gave to every beggar who knocks on the door we’d be as poor as pauper soup.’

It seemed that the whole town had forgotten what it was to be poor and old and cold and desperate.

At the top of the village he was directed to the priest’s house by the warmly dressed inn-keeper’s wife.

‘It’s the Church should care for ancients like you. The priest is a man of God, after all, or so he tells us as he pockets our tithes!’

Limping badly by now the beggar followed the directions and soon came to a handsome stone house surrounded by a high wall. He pushed open the gate and made his way to the back door. As he passed the dining room window, he saw the priest sitting at a table laden with food. There was fish and venison, pies, a great sirloin of beef.

The priest graciously left his meal for a moment to talk to the old man. He kindly informed him that he was very sorry, but that there was nothing suitable in the house to give a beggar. He would, however, say a prayer for him that very night and God would provide for him sooner or later if he only had faith. Then, with the air of someone who had done a noble deed, he smiled, nodded sympathetically and closed the door firmly.

The old man shambled back along the garden path. There was only one more place to try: the castle. There it stood, rich and powerful. The main gates were open, for this was a time of peace. There were a few soldiers lolling around in the courtyard eating bread, cheese and apples. When they saw the old man, they began to make fun of him.

‘Where are you gannin’ Granddad?’ they shouted. They stood over him and barred his way until he told them what his business was. ‘Oh food, eh? Well they’ve just fed t’ swine. Would thy lordship would care to join thy friends?’ They pushed him around from one to another, but as he did not protest, they got bored after a while and let him go, throwing their apple cores at his back as he limped towards the kitchen.

There his reception was even worse. The young scullions, black with soot and greasy from scouring pots, chased him around the room, hallooing and waving ladles and knives. Then they grabbed him by his skinny arms and threatened to put him on the spit next to the fat boar that was browning nicely there. In the end, the cook heard the noise and came in to the kitchen in a rage. He beat the boys into some sort of order, but he threw the old beggar out and told him that if he caught him doddering about there again he would set the dogs on him. The beggar could hear the dogs howling, mercifully shut up in their kennels.

Even more dishevelled now the beggar ran the gauntlet of the soldiers again and patiently walked back over the castle bridge. There he saw a brave sight coming down the road. The baron who owned the castle was returning from some outing. He was surrounded by his servants in bright livery. The beggar stepped forward into the path of his horse and knelt. Surely knight’s honour would not allow him to leave an old man without shelter.

‘My lord! My lord!’ he cried. ‘Help for God’s sake!’

The baron’s horse snorted but his master reined him in. ‘What can you possibly want from me, old man?’

‘Food, Sir, shelter for one in desperate need. I asked your folk but they taunted me and threw me out.’

‘Get your insolent body out of my path!’ roared the baron. ‘Where are the dogs?’

The beggar cringed and shuffled hastily out of the way as the baron’s horse sprang forwards over the bridge. Soon the castle’s doors were fastened behind their lord.

The sun was setting now. The old man had nowhere to go except onwards. The road out of the town was steep and icy, but he trudged forward up out of the valley; it was filling with grey evening mist. On the brown winter hills the last sunlight still glowed, but the cold was already creeping out from the shadows.

At the last turn of the road before the moor brow there was a cottage. It did not look very inviting for it was a single-storeyed low building, thatched with turf, not much different to a cow byre. Still, the old man had caught a glimpse of cheerful firelight shining from the single window, so he knocked tentatively.

The door was opened by a wiry middle-aged man with a weather-beaten face.

‘I’m sorry to trouble you –’ began the old man, but the shepherd (for that is what he was) gestured for him to enter even before he finished his sentence.

‘Come in, grandfeyther,’ he said, ‘come in and get a warm by the fire. You look half-starved with cold!’ Gratefully the old man entered and stretched out his old trembling hands to the warmth.

‘Sit down. There’s nobbut one chair but I can tek t’stool.’ The shepherd indicated a roughly carved armchair and the old man sank gratefully into it.

‘Thank you, maister, I’ve been walking all day.’

The shepherd looked thoughtful. ‘Thoo’ll not have etten, then, I guess. Not if thoo’ve been down yonder. They’re so near down there they’d skin a flea if they could catch it. Dinna thoo worry, I’ve bread an’ cheese an’ a slip of fatty bacon’ll set tha up like a lord. A drop of ale too, if thoo wants.’

‘But that’s your meal.’

‘Eh well, they say shared bread is sweeter! Put thy feet up while I fettle it.’

And so the old man got food and drink, little enough, it is true, but given with as much cheerful insistence as if the shepherd had a full storeroom. They chatted together after the meal, with the old man telling of his travels, the shepherd of the strange ways of mountain sheep. Then the shepherd made up a bed for himself by the fire, insisting that the old man sleep on his rough pallet, covered with warm sheepskins.

When the shepherd woke the next morning the old man was not there.

‘He’s left betimes,’ he thought, sorry to lose the chance of further talk, for his was a lonely life. As was his custom he opened the door and stepped out to see what the weather was doing. Then he saw that his guest had not gone. He was standing with his back to the cottage, staring down at the still-sleeping town. It seemed to the shepherd that he looked taller and straighter than he had been the night before and that the light of the newly risen sun had changed his white hair to gold.

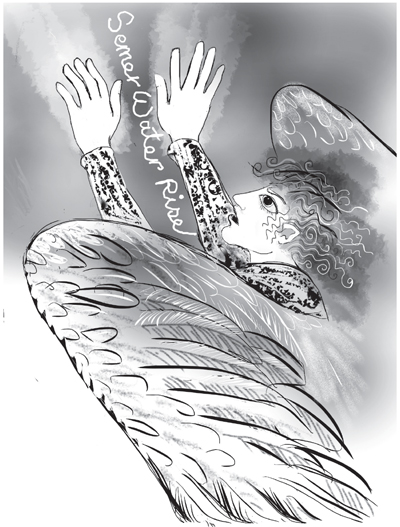

‘I hope tha slept sound?’ he asked. At the sound of the shepherd’s voice, the old man turned towards him. The shepherd gasped, doubting his own eyes. Where were the lines, the wrinkles? Where were the rags? The person who stood there dressed in shining robes was young and beautiful – beautiful in a way that made the shepherd tremble with fear.

‘Wha is thoo, (who are you) my lord?’ he whispered, falling to his knees.

‘Do not be afraid!’ said the young man. ‘You merit nothing but the highest praise. You took in a stranger and fed him when you had almost nothing. May you be happy! It is those without kindness who should tremble!’ He stared once more at the town and there was no mercy in his gaze. The sun began to dim as he grew taller and more terrible. Black clouds appeared from nowhere, borne on a rising wind. He flung out his hands in a wide gesture that seemed to embrace the whole town. Then he cried in a loud voice:

‘I call thee Semerwater, rise fast, rise deep, rise free!

Whelm all except the little house that fed and sheltered me!’

Instantly the black clouds over the town exploded with thunder and lightning; rain poured down. From every keld and beck in the valley great gouts of water spouted up in torrents, foaming and rushing with waterfalls becoming geysers. Spray filled the valley. The roar of water grew and grew; it was deafening but not so deafening that the shepherd could not hear the screams of the townsfolk as they tried in vain to escape their doom.

The radiant figure turned once more to the shepherd who was still kneeling, filled with fear and grief. There was a brief smile and a hand raised in blessing, then without another word the angel spread its magnificent wings and flew away into the pale-blue sky that still shone beyond the rolling clouds.