North Yorkshire Folk Tales (10 page)

Read North Yorkshire Folk Tales Online

Authors: Ingrid Barton

The children consider this interesting piece of animal physiology. ‘And does it make a noise?’ asks Paul.

‘Oh, there’s a terrible howling shriek when it catches its prey, but normally you’ll never hear it creep up behind you because its feet,’ she drops her voice to a whisper, ‘make no noise!’

‘No noise. Even when it’s a horse?’

‘Absolutely no noise. Its feet are as quiet as Tabby’s. The only sound you’ll ever hear comes when it’s very close to you. Just imagine, you’re coming home along the road one night and get a funny feeling that something is following you. You look around but you can’t see anything in the darkness. You go on a while but sooner or later …’

‘What?’

‘You’ll hear,’ Puff, puff, ‘a strange clinking-clanking noise.’

‘Like a harness chain?’

‘No, like a chain in a dungeon, a great big heavy chain. Bargest has one around its neck!’

‘What do we do if we hear it?’

Granny looks around at them all. They stare back expectantly but at that very moment there comes a muffled sound of clinking – or is it clanking? – a chain! The children gasp. Granny gets to her feet (dropping Tabby, hissing, to the floor). She clutches her heart dramatically and points with a shaking finger into the darkness of the room behind the children. ‘

YOU

RUN

!’ she shouts at the top of her voice. ‘

RUN

FOR

YOUR

LIVES

!’ And all the boys do just that, rushing for the stairs or the back door.

‘That got ‘em!’ says Granny, sitting down again. She knocks the ashes of the pipe out on the fender. Tabby jumps back up instantly. Sophie and Sarah, who, strangely, have not run away, are smiling and giggling a little.

‘Good work, Sophie!’ says Granny. ‘What was it Sarah gave you?’

‘Gyp’s old chain!’ Sophie holds up the dog-chain she has been hiding behind her back.

‘So, when will you tell us about the Gytrash?’ she asks.

HE

B

ARGEST

OF

T

ROLLER

’

S

G

ILL

Wharfedale

There was once a foolish man called Troller who decided that he wanted to see the bargest, though all his friends warned him against it.

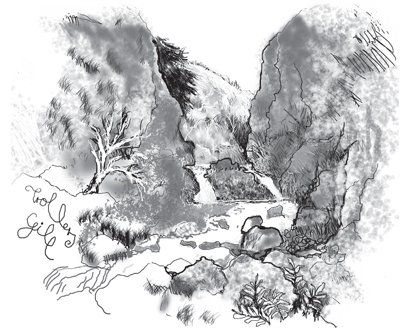

He decided to wait at a place it was known to inhabit, a dark gill between rocky cliffs where the Skyreholme Beck pours through a narrow channel before joining the Wharfe. No sane man would dare it at night, for though the fissure is very narrow, the gorge that the water has cut is very deep; any false step would mean death. The roar of the water in winter is deafening, the thunder of it resounding throughout one’s whole body.

Troller would not be deterred. He dabbled in magic and believed that he had a charm that would protect him from the bargest while allowing him to defy and perhaps even control it, like a magician of old. He was obsessed with the idea, drawn to the horror and convinced that he was the hero who would bend the creature to his will.

He rose from his bed at midnight and, armed only with a small ash twig, set off in the moonlight for the gill. The deep sound of rushing water beneath him did not daunt him. He felt only excitement as he reached a twisted old yew tree at the edge of the gill and knelt beneath it. With the ash twig he drew a circle around himself in the earth, turned himself clockwise three times, knelt and kissed the ground three times. Now, he believed he was safe, fool that he was, and settled down to wait.

On a nearby hill there was a shepherd camping out with his sheep to protect the newborn lambs against predators. It was he who caught sight of what happened next and later told the tale in Skyreholme village. His attention was first drawn to the gill by the sound of Troller’s voice calling out a challenge to the bargest.

‘Come and meet me, Bargest, if you dare!’

Curious, but glad he was no closer; the shepherd peered towards the beck. He saw a spectral green light that began to glow along the gill illuminating the rocks. As it grew brighter, it was accompanied by the ominous sound of a clanking chain, which swiftly became louder and closer. There was a sudden rush and clatter of falling stones. The shepherd’s blood ran cold as terrible shrieks burst without warning from the depths of the gill – whether those of a man or a beast he could not tell. They came again and again, dying away at last in a rattling howl that echoed across the moors. The shepherd and his dog waited, unable to move from fear, but they heard no more. The ghastly light died away and the beck flowed on undisturbed.

The shepherd was far too terrified to go and see what had happened. All night he huddled with his trembling sheepdog in the little lambing hut, unable to sleep, but the morning brought them more courage and they left the sheep and ventured down into the gill together. Almost immediately the dog began to bark.

Beneath the old yew tree lay Troller, his eyes open but unseeing, his face frozen in an expression of agonised terror. At first the confused shepherd thought that he must be wearing his red Sunday waistcoat, then he saw that terrible claws had torn open the poor man’s chest. The remainder of his heart’s blood was slowly trickling down into the beck.

From that night on, the place has been known as Troller’s Gill.

HE

F

ELON

S

OW

OF

R

OKEBY

Northern Moors

Ralph de Rokeby had a problem: she was large and fierce and covered with rusty-red hair. She was a pig, a sow, a felon sow vicious beyond belief!

Sows can be aggressive when defending their piglets, but this sow had no piglets. What she did have is ripping eye-teeth and molars that could crush bone like a twig. Larger than three ordinary sows she ranged the side of the little River Greta like a warlord, attacking – and sometimes killing – anyone who came near her.

As the poem says: ‘Was no barne that colde her byde.’ (Meaning there was no man who could stand up to her.)

Baron Ralph did not know what to do with her; none of his men dared go near her so he could not kill her for food and he hesitated to try breeding from such a monster. In the end, the exasperated baron decided that he would give her away. There was a daughter house of Grey Friars in nearby Richmond and he knew that, being a begging order, it was always short of food. ‘I’ll give the cursed thing to them,’ he thought. ‘Kill two birds with one stone. Get rid of the sow and benefit my immortal soul at the same time!’ He smiled wickedly.

The friars were overjoyed at the prospect of roast pork.

‘There’s just one thing,’ the baron told them. ‘You’ll have to bring her home yourselves.’

Well, that was not a problem; they would just tie a rope to her leg and drive her home with a stick. ‘Better take a couple of strong men with you,’ suggested Baron Ralph carelessly, ‘just in case.’

Friar Middleton was selected for this task and he picked two lay friary servants to help him, Pater Dale and Brian Metcalfe. The three men set off merrily with their rope and stick. They chatted of chitterlings and bacon, or stuffed chine and sausages.

They had no trouble at all finding the sow. There she was, lying under a tree by the River Greta. The three stopped abruptly.

‘Holy Mother of God!’

They stared in amazement. ‘Bacon for months, boys,’ exclaimed Friar Middleton. ‘Where’s that rope?’ Cautiously he began to approach the sow. She lifted up her head to watch him and very slowly got to her feet. Her muddy snout went snuffle, snuffle and her little red eyes peered at them from under her rusty eyebrows. She was about the size of a Shetland pony – but much more dangerous, as Friar Middleton discovered when she charged. Her trotters thundered over the ground. The three men turned and ran back into the wood, but the sow was much faster than any of them had expected and they had to hide behind trees. Their blood was up now, however; there was bacon at stake!

‘We’ve got to get that rope on her leg!’ shouted Friar Middleton. ‘You two grab her round the neck and wrestle her to the ground while I tie the rope. Altogether now: one, two, three!’

It was not an heroic scene. The sow shook off Peter and Brian like drops of water and chased the friar into the river. When she turned back to deal with the others, Brian just managed to avoid being run down by shinning up a tree, and Peter was chased round and round cursing and shouting for help.

The men were determined not to give up; they regrouped and flung themselves at the pig. Friar Middleton leapt onto her back and had a short but exhilarating ride before being flung into a briar patch. Peter made the rope into a noose and tried to lasso the sow’s head. There was a lime kiln in the wood, used for burning chalk into lime for the fields. The sow avoided the noose and backed abruptly, managing to get her backside stuck in the entrance to the kiln.

‘Quick! Get the rope on her!’ Peter slipped the noose over her head.

‘Got her!’ The three shouted with triumph, punching the air.

Now that she was stuck, the sow seemed to quieten down. She stood panting, appearing beaten. The men took hold of the rope and began to haul. The sow’s rear slowly became unstuck. As soon as she felt herself free, however, she suddenly leapt forward and attacked again, vicious jaws snapping. She took a lump out of Brian’s calf and butted Peter violently into a thorn bush. When she turned her attention to Friar Middleton, he did not stop to fight but leapt up into a nearby sycamore tree with un-friarly agility.

They had reached a stand-off; one man clutching his bleeding leg; one gasping for breath; one sitting like an unwieldy grey bird in a tree; the felon sow strolled back and forth keeping watch on them all.

Now Friar Middleton began to grow angry at the sow’s attitude. It was all very well for her to attack ordinary men like Peter and Brian, but he was a properly ordained friar and deserved more respect. He remembered how the birds fed St Cuthbert and how St Francis, the founder of his order, had preached to wild animals. She was an ignorant creature, he reflected, and would be improved by being instructed in the gospels. He slithered down the tree and, raising his hand in a dramatic gesture, he began to speak.

‘What’s he doing?’ hissed Peter to Brian.

‘I think he’s preaching to the sow.’

‘In Latin?’

‘In Latin.’

‘The sowe scho wolde not Latyne heare.’ Recovering from what was no doubt surprise at her enemy’s strange actions the pig squealed her rage and charged once more. Once more, the good friar had to take to his heels and flee to the wood.

When Baron Ralph saw his sow return home to her sty that evening, he noticed the rope hanging from her neck and knew that there had been a fight. He raised one eyebrow in amusement but said nothing. The sow settled down to sleep, well satisfied with her day.

It was a battered, scratched and miserable trio who stood before the warden of their friary attempting to explain why they had been defeated by a pig. Friar Middleton swore that she was not really a pig but the Devil in disguise.

The warden was not pleased with them, but neither was he going to give up. He settled down to write two letters. One was to the famous Gilbert Griffiths, a most renowned man-at-arms, and the other was to a well-known Spanish saracen-slayer. He begged them to go to Rokeby and slay the felon sow; a monster well worthy of their skill, he told them. In return, the friars would pray for their souls forever.

The two warriors could not resist the challenge and so the sow met her match at last – though vegetarians will be pleased to hear that she nearly managed to castrate the Spaniard before Gilbert felled her with his good sword. He took her back to Richmond cut in half and carried in two panniers strapped to a sturdy packhorse.

When the friars saw the pork arrive, their joy knew no bounds.

O how lustily they sang ‘Te Deum’ (We praise thee O God) before that night’s dinner!

HE

G

YTRASH

Western Moors

On the road from Egton Bridge to Goathland is a farmhouse called Julian Park. The land on which it is built was once, according to legend, the site of a castle built by an early member of the local de Mauley family. He was Julian de Mauley – and he was evil!