North Yorkshire Folk Tales (6 page)

Read North Yorkshire Folk Tales Online

Authors: Ingrid Barton

The friar considers. ‘Come to the greenwood, eh? Well, we friars are supposed to preach to the poor. I might be able to bring some smattering of holy learning to you poor benighted souls. But tell me first, do you have venison pasties in the forest?’

‘Of course! What else are the king’s deer for?’

The friar smiles broadly. ‘Then Friar Tuck is your man. Lead on!’

G

IANTS

O

N

G

IANTS

In the days before Darwin, people imagined their ancestors to have been much bigger than themselves; after all they were closer to the hand of God than we dwellers in degenerate times. Surely they must have been giants of men and women, not just larger but stronger, braver and more skilled than their feeble descendants! When King Arthur’s bones were conveniently discovered by the monks of Glastonbury in the twelfth century, no one was surprised that they were of giant size, indeed, that was considered proof that they really were Arthur’s bones.

After the collapse of Rome, much technology was lost along with knowledge of the past. The ruins of Bath became the work of giants, Stonehenge their temple and long barrows their graves. Only lightly converted to Christianity, people knew that their ancestors had worshipped other gods, had perhaps been descended from those huge gods, mountain-crushers, sea-drinkers.

The half-forgotten gods were regarded as devils by the new Christian Church, which took every opportunity to vilify them. Eventually old gods, ancestors and the Devil became gloriously confused. This explains why there is sometimes uncertainty in European folk tales as to whether the villain of a story is a giant or the Devil (

See

The Devil’s Arrows).

As folk tales get closer to our own time, belief in real giants waned. No longer terrifying, they seem to become increasingly stupid; often tricked, as in ‘Jack the Giant Killer’, by the sort of thing a baby would see straight through. However, the four Yorkshire giants in this chapter are still powerful: one is a kind road-builder and three are, let’s face it, pretty seriously nasty.

HE

G

IANT

OF

D

ALTON

M

ILL

Western Moors

Jack was a lad full of mischief. He skived off any work whenever he could, not because he was lazy exactly, but because he was more interested in the things going on around him. He loved to wander the wild moorland at Pilmore near Topcliffe where he lived. There he collected birds’ eggs and set snares for rabbits, as was commonly done by lads in those days, but as well as eking out the family’s food, he also liked to watch things. There was plenty to entertain him: not just dragonflies, tadpoles or frogs, but deer, foxes and badgers as well.

One day he was lying on his front peering into a pool when a huge shadow fell across him. He looked up: it was a giant, a very big giant with only one eye.

Jack immediately knew who he was; everyone did. His mother had warned him only that morning, ‘Don’t go on the moor, Jack, or the giant of Dalton Mill might get you!’ He had, naturally, ignored her. Now he was realising, too late, that not everything your mother tells you is rubbish.

The giant reached down and picked up Jack as easily as if he had been a stick. Jack kicked, struggled and shouted, but, of course, no one came to help him.

The giant carried him up hill and down dale until they came to the mill. Dalton Mill has been rebuilt several times over the years, but when the giant lived there, it was a terrible place. You could smell it from miles away, and when you got closer clouds of flies would rise up, buzzing, from its gloomy walls. You see, the giant did not mill wheat – he ground human bones. Every couple of days he went off hunting for people, dragged them back to his mill, butchered them and then ground their bones into flour. The meat he would either cook into a nasty stew, or just eat raw and dripping. The bone flour he would mix with blood and bake into loaves of bread. They were a bit on the heavy side but the giant enjoyed them. After dinner, he would lie on the floor or in his chair by the fire and sleep, his big knife clasped firmly in his hand.

Jack thought that he was going to die as the giant strode up to his horrible mill. He was carried through the door and thrown carelessly onto the bloodstained floor. He waited, frozen with terror, for the giant to get out his famous knife, long as a scythe blade, so people said – but to his surprise the giant bent awkwardly down to him, and said ‘I’ll not eat tha if thoo’l work for me.’

It seems that the giant was getting old and a bit rheumaticky. He found it hard to do all the things that a mill requires to keep working properly; cogs need oiling and grindstones need dressing – especially when you use them to grind bones!

Jack grabbed the chance of survival with both hands, even if it meant that he was now the giant’s prisoner. There was only one door to the mill, which the giant always carefully locked when he went out.

He began to learn something of the miller’s art whether he wanted to or not: there was absolutely nothing else to do and he knew better than to ignore the giant’s instructions. He also learned to make himself scarce and put his fingers in his ears when the giant brought his victims home.

What did he eat? Don’t ask!

The giant had a truly nasty dog called Truncheon, who was a smelly, scurvy- and flea-ridden snappy dog who delighted in making Jack’s life a misery, nipping his ankles and lifting its leg on him when he was sleeping. Jack did not dare do anything to Truncheon in revenge, because the dog was the giant’s best mate. Their eating habits were very similar; sometimes Jack felt quite sick hearing them both gobbling down their dinners, growling when one thought the other had got too close.

Seven months – or was it seven years? – went by. Jack worked for the giant, fettling the machinery, fetching and carrying, doing an occasional mop up. He kept looking for a chance of escape but he never found one. The giant slept very lightly and that one eye was always half open.

One day Jack was idly looking out of the window, feeling more than usually homesick and miserable. It was sunny and hot outside. The moors would be full of life, he thought, and here he was shut up away from everything. It must almost be time for Topcliffe Fair, he realised with a pang. He loved Topcliffe Fair.

That afternoon when the giant had eaten his dinner and was stretched out on the floor, his head on a sack, looking as relaxed as he ever did, Jack asked if he might go to Topcliffe Fair as he had not had a single day off yet.

‘I’ll come straight back afterwards,’ he said, looking at the giant as innocently as he could.

The one eye opened with a snap. ‘What sort of gobshite do you think I am?’ he said.

So that was that.

‘Right,’ thought Jack to himself, ‘this means war, thoo mean great naff-head, thoo vicious, ungrateful old – old –’ but he couldn’t think of a bad enough word.

Jack laid his plans – well, he would have if he could have thought of any plans to lay. The giant’s eye followed him more often than ever now and when its owner was not around the horrible dog was always there, scratching and drooling and waiting to give him a nasty nip.

The weather grew hotter and the mill smellier. Jack watched the giant after dinner hoping that the warmth would make him sleep more deeply. Several times he managed to make it to the door before that big eye opened and looked around for him.

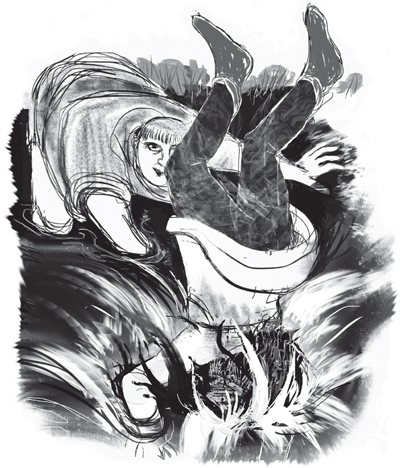

One baking hot afternoon, the giant did indeed fall into a deeper sleep than usual. As Jack watched, he saw the grasp on the terrible knife slacken. The huge fingers uncurled a little. Jack held his breath and gently eased the knife out of the giant’s fist. He gripped its handle tightly and looked at the sleeping monster; there was only one thing to do. Taking a deep breath Jack stabbed the knife with all his force into that one evil eye.

The giant uttered a terrible scream and, as Jack leapt away, he struggled to his feet fumbling with both hands at his wounded eye.

‘I’m blind! I’m blind! That miserable little worm has blinded me! Get him, Truncheon!’

He lunged, shouting and swearing around the room, thrusting his hands here and there to catch Jack. ‘I’ll catch thoo! I’ll squash thoo!’ He threatened Jack with every terrible death he could think of – and they were many! Eventually he realised that he would never catch Jack that way, so he went to the door and stood with his back to it.

‘I’ll stand here while I brak thah neck! I will! I’ll never rest! Thoo’ll never get out!’

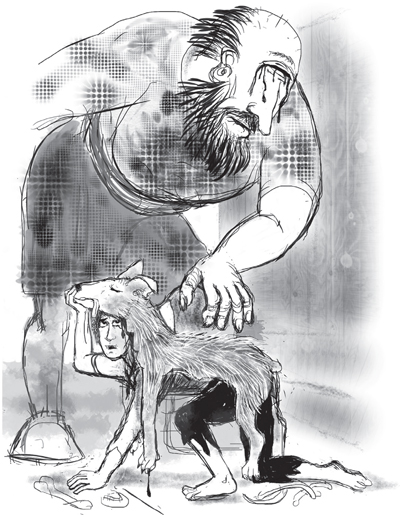

This was an unforeseen setback. Jack looked around. The horrible dog was barking and jumping about showing its yellow teeth, though it did not attack. (It was, basically, a coward.) Jack had a sudden idea – or perhaps he remembered an old tale his mother had once told him – he caught Truncheon by the scruff of the neck and, before the dog knew what he was doing, he had cut its throat with the giant’s knife.

Then he skinned it.

It took time because his hands were shaking so much and because all the while the giant was moaning and howling so loudly he could hardly think. When the skin was ready, he pulled it over his head and back. He had left the head on and, supporting it with one hand, he crawled towards the giant, whining. He butted the giant’s leg with the head and barked in quite a good imitation of Truncheon. The giant reached down a hand and felt the dog’s head. Jack waggled it a bit and whined again.

‘Tha’s sorry for me, Truncheon. Good dog, faithful dog!’ He patted the dog’s back. (Jack was nearly knocked over!) Another urgent whine. ‘Want to go out for a piss, does tha?’

Slowly the giant unfastened the great lock and slid back the huge bolts. The door swung open. Freedom! Jack scuttled out as fast as his legs could carry him into the beautiful summer sunlight. Throwing off the dog’s skin, he ran and ran and ran until he was safely back home.

![]()

Later that evening Jack, thoroughly washed and with his joyful parents, was to be seen at Topcliffe Fair telling his story to anyone who would listen.

‘A likely tale!’ some said, but others wondered if there might be some truth in it.

Time went by and nothing more was heard of the giant. No more unwary travellers or lonely shepherds disappeared. People began to think Jack’s tale might be true, however unlikely. Soon a well-armed band of brave folk ventured to Dalton Mill. There, right in front of the door they found the giant, dead and covered with a veritable mountain of buzzing flies. Jack’s blow had obviously done more damage than he had thought and pierced the giant’s brain.

They buried the giant in front of his house – the big mound is still there. The knife was kept inside the mill and shown to visitors as proof of the story well into our own time.

Jack recovered quickly from his adventure. Thanks to his stay with the giant, he was so skilled in the miller’s art that a few years later he actually got a job in that very trade (as far away from Dalton Mill as he could get), but to the end of his days he could never stand dogs!

ADE

AND

H

IS

W

IFE

B

ELL

Western Moors