North Yorkshire Folk Tales (2 page)

Read North Yorkshire Folk Tales Online

Authors: Ingrid Barton

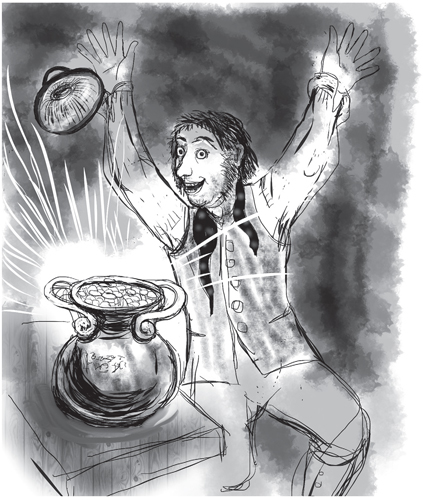

As he looked around he thought he could see a lightness in one corner. He peered closer: white blossom. A large elder tree stood there. He strode bravely across and thrust his spade between the cobblestones beneath the tree. They put up a good resistance for a while but he was persistent and soon he was able to pull several out. Beneath them he thought he could see a dark hole. Our man thought of giant worms and poisonous toads, but he gritted his teeth and reached into it. Almost at once he touched something cold and smooth – a box, or perhaps a pot or something. He glanced around quickly but no one was around. Swiftly he pulled it up – it was heavier than he expected and he had to use both hands – and then shoved the stones back into place. Standing up with difficulty, he hid the pot as best he could under his coat and staggered home.

In the dim light of his rush-lit cottage, our man excitedly brushed the soil off the pot. He could to see that it was ancient. On its lid there was writing. Our man was not too good at reading, but even he could see that the letters were not like the ones he had learned at dame school. He briefly wondered if it was a curse. ‘In for a penny, in for a pound,’ he muttered to himself with a shrug and wrenched the lid off.

There was a moment’s pause, then he leapt to his feet and did a silent dance, for the rush-light now sparkled on gold; coin after coin of solid gold!

The news of our man’s sudden wealth was a nine-days’ wonder in the village. Some folk were pleased at his good fortune, especially as he did not move out but spent his money locally. ‘He’s careful, but he’s not mean,’ they said. Some, inevitably, were jealous, but that is the way of the world since time began, and you can be sure that the jealous ones were just as keen to be bought a pint of ale by our man as the others were. People speculated about where he had come by his fortune (was he secretly a highwayman? An alchemist?), but he said nothing, only smiled, and, as no one local had been robbed recently, in time the gossip died down.

He showed the empty pot to the vicar, hoping that he would be able to read the strange writing, but though the learned man hummed and hawed it was clear that his learning wasn’t great enough. ‘Some pagan druidic language, I expect,’ he said.

There had seemed to be plenty of gold when our man first opened the pot, but it cost a great deal to set up the house of a wealthy man, and the same again to set up a carriage. Our man was careful, but even so the time came when the money began to run out. Needless to say he kept the fact to himself, but soon he was living on tick and began to worry. He was going to have to borrow money and he only knew one way to do that, much though he hated the idea.

One day he surprised his coachman by giving him the day off and driving himself out alone in a little pony trap. He headed into Thirsk. Down a narrow street, he drove and knocked on an unremarkable door. A maid answered it.

‘Is the Jew in?’ demanded our man.

‘Mr Isaac is within,’ she replied coldly. ‘Do you have an appointment?’

‘Damn it!’ spluttered our man. ‘I need brass!’ She led him to a comfortably furnished room where the moneylender was sitting at his desk.

‘This person has come to see you,’ announced the maid disdainfully. Mr Isaac saw his new client was upset, but he did not lend money just for the asking. Politely but firmly he delved delicately into his visitor’s history. It was a sign of our man’s desperation that, for the first time, he found himself telling the whole story.

Mr Isaac was fascinated. ‘God has been good to you,’ he said. ‘Do you still have the ancient pot with the strange writing on it?’

‘Aye, but vicar could mak nowt on it.’

‘I tell you what,’ said Mr Isaacs, ‘I will lend you enough money to pay your immediate debts – I regret that your collateral isn’t good enough for more – but the one condition is that you will show me that pot. I am a collector of antiquities in a small way. It would give me a great deal of pleasure to see it. Perhaps you might be persuaded to part with it for a suitable sum?’

And with that our man had to be satisfied.

A few days later, he returned with the pot. The old man took it to the window and inspected the writing with a large magnifying glass. He gave a short laugh. ‘Very interesting!’ he said.

‘Oh, aye!’ said our man. ‘But when shall I have the money?’

Mr Isaacs put down the glass. He went back to the fire and sat down. He put the pot on his desk. ‘You can’t have it,’ he said.

Our man’s face went as red as a turkey cock. ‘What? But you said! It were a bargain, spit and shake hands, you said!’

‘You can’t have it,’ said Mr Isaacs, ‘because you don’t need it.’

Our man was not stupid, but at that moment, he really did look like a gormless gavrison. Mr Isaacs smiled. ‘The writing is Hebraic script. Would you like to know what it says?’ Our man nodded.

‘It’s a verse:

Look lower!

Where this stood,

Is another twice as good,

You are indeed favoured by God!’

‘Keep the pot!’ gasped our man, when he could speak. ‘And say nowt to anyone!’

Mr Isaacs inclined his head. ‘I can assure you that all our clients’ affairs are treated with the upmost secrecy,’ he began to say, but our man was already out of the door.

The second pot turned out to be, indeed, twice the size of the first. Our man had to take the pony trap with him when he went to get it. It had enough gold in it to last him – but who knows how much gold will be needed in a whole lifetime? Especially when you marry a willing lass and start fathering children a little late in life. Our man did not have to worry, though, for on the second pot was more strange writing – exactly the same as on the first. He knew what it meant now. He said nothing. A true Yorkshireman always likes to have a little something put away for a rainy day.

HE

W

HITE

D

OE

Wharfdale

It is Sunday. Folk are coming out of Bolton church when they see a white shape under the trees of the churchyard. At first they hang back, fearful of ghosts. Then, stepping lightly among the hoary gravestones, a snow-white doe comes towards them. It stops at a safe distance and regards them with its great brown eyes, poised to run.

The churchgoers give it a wide berth, but the next Sunday it is there again – and the next. Sunday after Sunday, it returns, now standing further back, by the graves of the Norton family. Folk agree that it is no natural deer, with its sad eyes, but appearing as it does on the Lord’s Day, neither can it be evil. No one attempts to drive it away.

Soon the gossip had a sighting at Rylstone church too. There is speculation as to whose ghost it might be, some favouring one deceased candidate and some another, but most agree that it is the fetch of Emily Norton, come to mourn at her brothers’ grave. ‘A sad tale,’ they agree.

![]()

Richard Norton had nine tall sons, archers and swordsmen all. They lived at Rylstone Hall and had a hunting lodge, Norton Tower, near Rylstone Fell where they stayed at times to hunt the red deer. He also had one daughter, Emily, who was quiet and pale and devout.

Among so many boisterous men Emily was often forgotten or neglected, left behind when they went hunting (for she would not join them) and silent as a mouse at the table where they talked loudly of their exploits. She loved them fiercely though: their easy grace on horseback, their rough playful ways and their good spirits. Best of all she loved to see them when they all knelt together at prayers in the evening, silent and respectful for once; a row of brothers united by their religion, a strong wall protecting the family.

She had a particular fondness for her eldest brother Francis and he returned it in the careless way of young men. He often brought her little presents, but one day he surpassed himself by bringing out from under his cloak a little fawn: a white one. It was tiny, bleating feebly.

‘A white deer is good luck!’ he told her. ‘I’ve never seen another. I thought you would make a good mother for it.’

Emily kissed him happily, though she soon learned the hard way what it is to care for another creature’s baby. The little fawn could go for a long time without food, but the moment that it smelt milk it would begin to struggle to its feet, and its bleating grew loud and shrill. The old family shepherd showed her the trick of putting her hand in the milk and getting the fawn to suck her fingers to persuade it to drink by itself.

The fawn survived and began to grow into a fine doe. It followed Emily wherever she went; they became inseparable.

But times were changing. Richard and his children did not realise how much. They were shocked to hear that King Henry had decided to put away his true wife, Catherine, and marry his whore, Anne Bullen. How was it possible for a marriage – especially one of such a long duration – to be dissolved on a whim?

Worse was to follow, for the king, no doubt influenced by bad council, foreigners and above all his base-born chancellor, Cromwell, seemed determined to break with the Holy Father in Rome and bring damnation upon the whole country.

The male portion of the family debated and argued at table and away from it. They were united in their determination not to change their faith in any way. ‘How can a king change what God has ordained?’ they asked. In this, they shared the opinion of most of their neighbours in the North. What they could not agree on was what to do about it. The younger hotheads were all for local landowners raising troops and riding to London to demand that the king change his evil advisors. Older and wiser heads pointed out that this king was not a man who brooked criticism from anyone. ‘Your heads would decorate London Bridge before your feet were out of the stirrups!’ said their father.

Francis said, ‘The king listens to arguments. We should write to him setting out our points carefully.’ But the other sons laughed at him, saying that they were not lawyers but the sons of a gentleman. In the end, the wiser councils prevailed and nothing was done – for the moment.

Meanwhile Emily’s doe was fully grown. She saw that the time had come for her pet to return to the herd and that it would be cruel to keep her a prisoner. She knew that her brothers would never kill her doe and so one day she took her into the deer park, where the herd was feeding. The doe trembled with excitement when she saw others of her kind and tentatively approached the herd. A fine stag caught her scent and came trotting out to meet and claim her. Emily returned home a little sad, but knowing that she had done the best she could for her friend. In the years following Emily often saw the doe running with the herd; flashing in the sunlight as the deer streamed along a hill or shimmering white among the trees of the wood, but they did not approach each other again.

One day a neighbour came galloping to the gates of Rylstone Hall. He brought news that, at first, no one could believe: the king had ordered commissioners to investigate all monasteries and decide whether they were being properly administered. They had the power to close any that were found wanting.

‘It’s just an excuse invented by court lawyers for stealing the Church’s property!’ declared Richard.

‘Like enough it’s the king who will eat the goods,’ said Christopher, another of the sons. ‘He grows as fat as Pig Ellen – and as greedy!’

His father struck him for insulting the king, but his view was silently held by many. The news soon spread to the commoners and they were consumed with fear. If the monasteries closed, who would help to feed the poor in times of famine? Who would provide them with care when they were ill? Who would keep the powers of darkness at bay?

The great landowners of the North and their people were never friends of change. They wished to live the life that their forefathers had lived, safe in the certainties that had sustained them for centuries: their religion, administered by priests in the magic language, Latin; the social hierarchy where everyone knew their place, their responsibilities, their obligations. New ideas, new men, new practices they rejected as dangerous to order, and order, in a troubled region like the North, was thought more important than anything.

Emily heard talk of a pilgrimage as she sat at the family table. It would not be to a holy place but it would be a holy thing itself, formed of abbots, priests, lords and ordinary people. They would go to London humbly and prayerfully to beg the king to spare the monasteries and, by ridding himself of certain evil councillors, to make his people happy.