Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War (20 page)

Read Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War Online

Authors: Viet Thanh Nguyen

The real drama of

White Badge

is not between Koreans and Vietnamese, but between Koreans. Han Kiju’s former comrade, Pyon Chinsu, has contacted him in order to ask a final favor—shoot him and put him out of his postwar misery, which occurs against the backdrop of democratic struggles opposed to the military dictatorship of Chun Doo Hwan. The novel closes with the meeting between Pyon Chinsu, peasant, and Han Kiju, intellectual, without letting us know whether Kiju can pull the trigger. Either way is defeat for soldiers who are neither rewarded nor recognized by their fellow citizens, especially the businessmen that benefited most from the war. Unlike the War Memorial of Korea,

White Badge

shows the costs and myths of martial manhood. Whether this manhood succeeds or fails is due in both cases to its submission to the American giant “who had never learned how to live outside his own world” and who has demanded that Koreans live in his, via his capitalism, his literature, and his (white) war.

34

In return, this giant offers Koreans the opportunity to exploit what historian Bruce Cumings calls “El Dorado,” or Vietnam, where Korean engineers from Daewoo rented rooms from my parents in our amiable provincial town.

35

The disgust with both Americans and Koreans is profound in these antiheroic novels, but there exists a heroic trend in Korean memory about this war found in songs such as “Sergeant Kim’s Return from Vietnam.” This heroic version of Korean war memory does not circulate outside of Korea, however. Instead, audiences outside Korea are most likely to know these antiheroic novels and the movie adaptation of

White Badge

. In this way, the Korean case is similar to the American one. Perhaps the global image of the war was so negative that heroic stories did not match the expectations of global audiences.

White Badge

’s 1994 movie adaptation (also called

White War

in Korea) is still perhaps the best-known Korean film about the war, and retains the novel’s antiheroic, anti-American qualities.

36

At the same time, the movie signals how Korean memories of the war increasingly emphasized the way that Koreans experienced the war. While the novel is remarkable in the war’s global literature for its Vietnamese perspectives, the movie eliminates most of them. Han Kiju’s mistress vanishes and the Viet Cong woman whom the soldiers sexually humiliate becomes a suicide bomber. Without sympathetic Vietnamese women, the movie, even more than the novel, becomes a drama about and between Korean men. Their struggle is not so much about their own moral ambiguity in Vietnam but about their postwar relationship to a Korean society poised between dictatorship and democracy in the 1980s.

The movie portrays these struggles and is also an outcome of these struggles. It depicts a war which helps transform Korea into a muscular capitalist society and enables Korea to tell more powerful, more expensive stories. The movie is part of an art form that says as much about its society through its technical achievement, made possible by the development of an industrial complex, as it does by its narrative. As with the War Memorial of Korea, however, the spectacular language of cinema oftentimes comes with more than just a financial cost. Film, as an industrial production, must return profit on investment more so than literature, where the stakes are smaller. While literature can more easily afford to take risky steps such as empathizing with the enemy, film oftentimes lags far behind, as in the big-budget movie

White Badge

. This movie, for all its antiwar qualities, was part of the “New Korean Cinema” that was one more sign of Korea’s global competitiveness.

37

New Korean Cinema has made Korean directors the darlings of the international film circuit and captured the attention of Hollywood. This cinema tells Korean stories and is itself a Korean story. As shiny as the latest line of Hyundai cars, this cinematic soft power is a material artifact of Korean accomplishment and affirms Korea as worthy of inclusion among the world’s first rank. Framed in this way,

White Badge

the movie erases Vietnamese characters and by its very presence as a movie about Koreans in Vietnam contributes to the global dominance of the Korean point of view over the Vietnamese, a dominance maintained by Korea’s ability to export this and other movies overseas.

Three more Korean movies about the war would follow

White Badge

, together signaling the convergence of memory and power through the industrial art of film:

R-Point

(2004), a horror movie;

Sunny

(2008), a romantic melodrama; and

Ode to My Father

(2014), a historical melodrama and box office hit. These polished, sleek movies, considerably more advanced than anything coming out of Vietnam, are technically on par with Hollywood movies and share a similar theme. As American war movies of the 1980s engaged in what scholar Susan Jeffords called the “remasculinization of America” after the emasculating loss of the Vietnam War, critic Kyung Hyun Kim argues that postwar Korean cinema likewise remasculinized.

38

All three movies show an embattled Korean masculinity in Vietnam and also embody a rising Korea through cinematic flashiness.

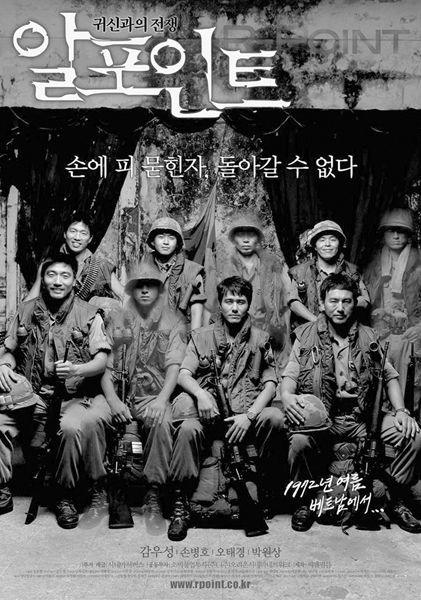

R-Point

follows a squad of Korean soldiers searching for a missing squad of their fellow troops. In an abandoned colonial villa, they encounter a ghost who has caused the deaths of those missing soldiers, a Vietnamese woman wearing a white

ao dai

who possesses these soldiers and makes them turn their weapons on each other.

39

As in American war movies, the Vietnamese woman is the most frightening figure of all. The most famous depiction in American film of the threatening woman is

Full Metal Jacket

, where a female sniper decimates an American squad until they capture and kill her. But in

R-Point

, the threatening ghost lives on, destroying all but one of the Korean soldiers for their sexual and territorial transgressions.

40

Ironically, the death of the Korean soldiers is also an absolution. Victims of their own “friendly fire”—even the last survivor is blinded—they cannot be held responsible in the same way that living American soldiers can.

41

The theme of absolution is also at the heart of

Sunny

, a strange and entertaining war film about recently married Soon-Yi, whose husband volunteers for the army because he believes his wife doesn’t love him (and she believes he has a mistress). Rejected by her in-laws and her family as a result of his abandonment, Soon-Yi travels to Vietnam to get him back. The only route is through becoming an entertainer for Korean and American troops, and she ships out with a bandleader who renames her Sunny, a name more appropriate for the Americans. Their degradation of her, and all Koreans, is driven home when an audience of American soldiers howls and leers at Sunny as she sings “Susie Q.” After the delirious GIs shower her with money, Sunny sleeps with their officer in exchange for his help in saving her husband. Her bandmates acknowledge her literal prostitution and their own figurative prostitution when they burn the dollars with which they have been paid. American villainy is rendered even more vividly when American soldiers shoot a little girl in the back and murder a Viet Cong commander who has spared the band members’ lives. In contrast to the evil Americans, Korean soldiers in the movie never commit atrocities. Shot, shelled, and ambushed in several battles, they are almost always on the defensive, terrorized by the enemy until Sunny’s husband is the last survivor of his ambushed squad. When Sunny finally meets this traumatized husband on the battlefield, she does not embrace or kiss him; instead, amid gunfire and shelling, she slaps him until he falls to his knees, the final frame of the film. As in

R-Point

, Korean men are the ones to be punished, both by Vietnamese and by women. But unlike

R-Point

,

Sunny

refuses to believe that Korean men did more than fight in self-defense.

Ode to My Father

is the story of Duk-soo, a refugee from the north who feels responsible for the loss of his father and sister during their flight. After his family is rescued by American forces, he takes on the responsibility of supporting his mother and siblings. He endures great personal sacrifice as a coal miner in East Germany and as a contractor in wartime Vietnam, but his hard work enables his economic success. His rise from beggar to middle-class patriarch mirrors the rise of South Korea from the 1950s until the present. The Korean war in Vietnam plays a small but crucial role in the transformation of both Korea and Duk-soo. As the war ends, communist forces trap him and other Korean contractors in a Vietnamese village. During a battle where Korean marines fight off the communists and rescue the contractors and friendly Vietnamese, Duk-soo is wounded when he saves a Vietnamese girl from drowning. Although he is permanently disabled, he is now the rescuer rather than the rescued, as is South Korea in relationship to South Vietnam. The story of

Ode to My Father

is harmonious with the story of the War Memorial of Korea in showing how South Koreans went from being abject and inhuman, in need of help during the Korean War, to human defenders of freedom during the Korean war in Vietnam. While the transformation of Korea is evident to all, Duk-soo’s heroism is unknown to his children, who also take for granted their father’s labor and suffering for them.

With these portrayals of wounded, victimized Korean masculinity beginning in

White Badge

, Korean cinema functions like American cinema of the war. Even if Americans depict themselves in criminal ways, the depiction is always shown through Hollywood’s bright light. Likewise with Korean war movies. As part of a New Korean Cinema that is not reluctant to depict Koreans antiheroically, some of these movies show that self-representation of the darkest kind is better than no representation at all. But viewing these films in sequence, from 1994’s

White Badge

to 2014’s

Ode to My Father

, what we see is a narrative that decreases darkness and increases revision of the past. Koreans are human in these movies, but more so, they are victims too, proxy warriors who do the bidding of the real villains, the Americans. This cinematic recasting of the other Korean war fits neatly with how Koreans can claim to be a “victim state” of the United States and its Cold War policy.

42

While Korea of the past may have been a vassal, Korea of the present pushes back, a competitor who demands worldwide recognition, both for its people and its products. In a world of global capitalism, commodities are more important than people and often travel more easily than people do. Like people, commodities are valued in different ways, expensive Korean goods more fashionable than cheap Chinese ones. In the case of Vietnam, one can find both expensive Korean products and expensive Korean people. Koreans have returned in unarmed force, as tourists, business owners, and students. Korea is seen everywhere, in hairstyles, pop music, movies, melodramas, and malls. For most Vietnamese, Korea and Koreans are spectacular images of a beckoning modernity, regardless of the realities underneath. For both Koreans and Vietnamese, this modernity requires amnesia about their previous shared past. Thus, while Korean commodities can be seen everywhere, memories of the Korean war in Vietnam are still hard to come by, even in their cinematic form.

When Vietnamese do recall Koreans, the memories are negative. At the Museum of the Son My Massacre, better known as the My Lai Massacre, a plaque in English and Vietnamese remembers the “violently atrocious crimes of the American aggressor and the South Korean mercenaries.”

43

The South Vietnamese who fought alongside Korean soldiers did not care much for them either. Nguyen Cao Ky, air marshal and vice premier of the Republic of Vietnam, accused them of corruption and black marketeering.

44

Average soldiers resented that American soldiers favored the Korean troops, whom they thought more aggressive. To add insult to injury, the Americans even made the South Vietnamese army buy Korean soy sauce to replace Vietnamese fish sauce.

45

The Vietnamese civilian view of the Korean soldiers was worse, for some of the Vietnamese remembered how, during World War II, when the country was under Japanese occupation, Korean soldiers were in charge of the prison camps.

46

And, according to Le Ly Hayslip, a peasant girl caught in the ground war in central Vietnam: