Octopus (20 page)

Authors: Roland C. Anderson

Plate 28.

This common octopus (

Octopus vulgaris

) in Bonaire could be described as boldâit is standing its ground and keeping its mantle inflated so it looks larger. James B. Wood.

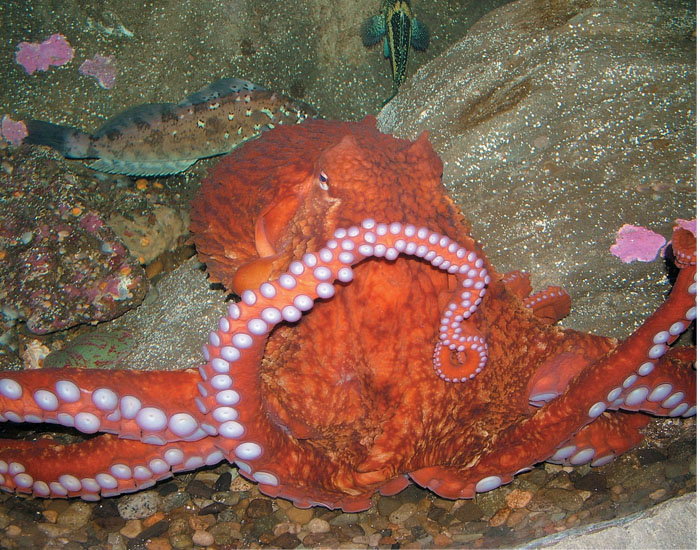

Plate 29.

This active male giant Pacific octopus (

Enteroctopus dofleini

) is not shy with aquarium guests. Seattle Aquarium.

Plate 30.

Foraging octopuses, such as this Caribbean reef octopus (

Octopus briareus

), keep track of where home is (spatial memory) and of where they are (working memory). Dry Tortugas National Park, Florida. James B. Wood.

Plate 31.

This common octopus (

Octopus vulgaris

) kept in a lab in Vienna is investigating a glass jar with a lid. Konrad Lorenz Institute. James B. Wood.

Plate 32.

A male common octopus (

Octopus vulgaris

) holding on to the front of an aquarium in Vienna shows the large sucker near the base of one of his arms. Konrad Lorenz Institute. James B. Wood.

Plate 33.

This pair of star-sucker pygmy octopuses (

Octopus wolfi)

is mating in a mounted position. Roy Caldwell.

Plate 34.

These two blue-ringed octopuses (

Hapalochlaena maculosa

) are mating in a mounted position, so close it's hard to tell they aren't just one animal. Roy Caldwell.

Plate 35.

Male Caribbean reef squid (

Sepioteuthis sepioidea

) have visual display contests over status and access to females. The lower male is making a more intense zebra display and will win this contest. Bonaire. James B. Wood.

Plate 36.

This little adult pygmy squid (

Idiosepius pygmaeus

) in Phuket, Thailand, is attached to an underwater leaf by her dorsal surfaceâa good hiding technique. James B. Wood.

Plate 37.

The common octopus (

Octopus vulgaris

) does well in captivity. Bermuda. James B. Wood.

Plate 38.

The Californian two-spot octopus (

Octopus bimaculoides

) is a good choice for keeping in an aquarium. John Forsythe.

8

Personalities

“P

ersonalities?” We can hear the skeptical reader asking, “Octopuses have personalities?” The simple answer is yes. When a species like the octopus has a big brain and is highly dependent on learning, different members of the species are going to behave differently, especially when faced with challenges related to survival.

Roland got us thinking about octopus personalities in 1987, when he wrote an article about the three species of animals at the Seattle Aquarium that volunteers gave names to: seals, sea otters, and octopusesâtwo mammal species and one cephalopod species. In the octopus group, there were Lucretia McEvil, who tore up everything she could in her tank, Emily Dickinson, who hid permanently behind the tank backdrop, and Leisure Suit Larry, described as ripe for citation of sexual harassment for excess touching if he'd been human. Volunteers gave these animals names because different individuals were behaviorally very distinct from one another, a characteristic they didn't see in fish or birds but one that reminded them of people.

Ten years ago, not many scientists were saying that there were individual behavioral differences in animals. Science had made a huge step forward in going from anecdotes about one or two animals to data from many. We were systematically looking at the average, making conclusions for populations or species but not for individuals. We said pigeons could home over a familiar range of up to 16 mi. (26 km), that mallard head tosses have a specific angle and differ from pintail head tosses in angle and duration. We might have said that rats can learn a T-maze in an average of XX trials, Y fewer than mice. Our ability to predict what members of a group could do was powerful.

The roots of Western science's attitudes toward animals are in two sources. One is our belief in objectivityâthat we can make value-free observations and experiments to get the truth about behavior. Eastern philosophers

hold the opposite attitudeâthat when you observe something, you inevitably change it. Turns out, we are learning that objectivity isn't really possible. Hank Davis and Dianne Balfour challenged the objectivity belief in 1992, collecting a series of accounts by behavioral scientists about the bonds between human scientists and their animal research subjects; Jennifer wrote an article, “Underestimating the Octopus,” included in that book. But the belief in objectivity is only slowly waning.