On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society (23 page)

Read On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society Online

Authors: Dave Grossman

Tags: #Military, #war, #killing

They would not misuse or misdirect their aggression any more Chapter Six

All Factors Considered:

The Mathematics of Death

A

soldier who constantly reflected upon the knee-smashing, widow-making characteristics of his weapon, or who always thought of the enemy as a man exactly as himself, doing much the same task and subjected to exactly the same stresses and strains, would find it difficult to operate effectively in battle. . . . Without the creation of abstract images of the enemy, and without the depersonalization of the enemy during training, battle would become impossible to sustain. But if the abstract image is overdrawn or depersonalization is stretched into hatred, the restraints on human behavior in war are easily swept aside. If, on the other hand, men reflect too deeply upon the enemy's common humanity, then they risk being unable to proceed with the task whose aims may be eminently just and legitimate. This conundrum lies, like a Gordian knot linking the diverse strands of hostility and affection, at the heart of the soldier's relationship with the enemy.

— Richard Holmes

Acts of War

All of the killing processes examined in this section have the same basic problem. By manipulating variables, modern armies direct ALL F A C T O R S C O N S I D E R E D

187

the flow of violence, turning killing on and off like a faucet. But this is a delicate and dangerous process. Too much, and you end up with a My Lai, which can undermine your efforts. Too little, and your soldiers will be defeated and killed by someone who is more aggressively disposed.

An understanding of the physical distance factor, addressed in the section "Killing and Physical Distance," combined with a study of all of the other personal-kill-enabling factors identified thus far, permits us to develop an "equation" that can represent the total resistance involved in a specific killing circumstance.

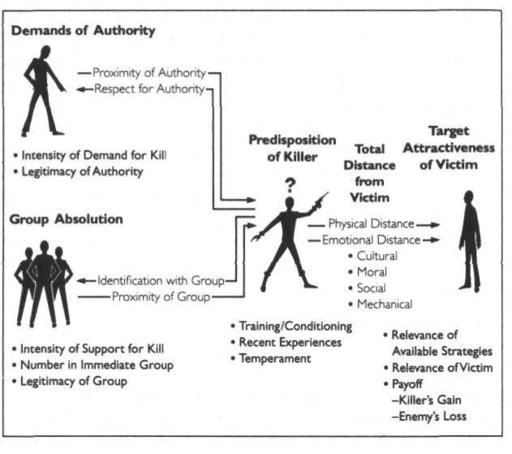

To recap, the variables represented in our equation include the Milgram factors, the Shalit factors, and the predisposition of the killer.

The Milgram Factors

Milgram's famous studies of killing behavior in laboratory conditions (the willingness of subjects to engage in behavior that they believed was killing a fellow subject) identified three primary situa-tional variables that influence or enable killing behavior; in this model I have called these (1) the demands of authority, (2) group absolution (remarkably similar to the concept of diffusion of responsibility), and (3) the distance from the victim. Each of these variables can be further "operationalized" as follows:

Demands of Authority

• Proximity of the obedience-demanding authority figure to the subject

• Subject's subjective respect for the obedience-demanding authority figure

• Intensity of the obedience-demanding authority figure's demands of killing behavior

• Legitimacy of the obedience-demanding authority figure's authority and demands

Group Absolution

• Subject's identification with the group

• Proximity of the group to the subject

188

A N A N A T O M Y O F KILLING

Intensity of the group's support for the kill

Number in the immediate group

Legitimacy of the group

Total Distance from the Victim

Physical distance between the killer and the victim Emotional distance between the killer and the victim, including:

—Social distance, which considers the impact of a lifetime of viewing a particular class as less than human in a socially stratified environment

—Cultural distance, which includes racial and ethnic differences that permit the killer to "dehumanize" the victim ALL FACTORS CONSIDERED

189

—Moral distance, which takes into consideration intense belief in moral superiority and "vengeful" actions

—Mechanical distance, which includes the sterile "video game"

unreality of killing through a TV screen, a thermal sight, a sniper sight, or some other kind of mechanical buffer

The Shalit Factors

Israeli military psychology has developed a model revolving around the nature of the victim, which I have incorporated into this model.

This model considers the tactical circumstances associated with:

• Relevance and effectiveness of available strategies for killing the victim

• Relevance of the victim as a threat to the killer and his tactical situation

• Payoff of the killer's action in terms of

—Killer's gain

—Enemy's loss

The Predisposition of the Killer

This area considers such factors as:

• Training/conditioning of the soldier (Marshall's contributions to the U.S. Army's training program increased the firing rate of the individual infantryman from 15 to 20 percent in World War II to 55 percent in Korea and nearly 90 to 95 percent in Vietnam.)

• Recent experiences of the soldier (For example, having a friend or relative killed by the enemy has been strongly linked with killing behavior on the battlefield.)

The temperament that predisposes a soldier to killing behavior is one of the most difficult areas to research. However, Swank and Marchand did propose the existence of 2 percent of combat soldiers who are predisposed to be "aggressive psychopaths" and who apparently do not experience the trauma commonly associated with killing behavior. These findings have been tentatively confirmed by other observers and by USAF figures concerning aggressive killing behavior among fighter pilots.9

190

A N A N A T O M Y O F KILLING

An Application: The Road to My Lai

We can see some of these factors at work in the participation of Lieutenant Calley and his platoon in the infamous My Lai Massacre.

Tim O'Brien writes that "to understand what happens to the GI among the mine fields of My Lai, you must know something about what happens in America. You must understand Fort Lewis, Washington. You must understand a thing called basic training."

O'Brien perceives both cultural distance and training/conditioning (although he does not use those terms) in the bayonet training he received when his drill sergeant bellowed in his ear, "Dinks are little s s. If you want their guts, you gotta go low. Crouch and dig." In the same way, Holmes concludes that "the road to My Lai was paved, first and foremost, by the dehumanization of the Vietnamese and the 'mere gook rule' which declared that killing a Vietnamese civilian did not really count."

Lieutenant Calley's platoon had received a series of casualties from enemies who were seldom seen and who seemed always to melt back into the civilian population. The day before the massacre, the popular Sergeant Cox was killed by a booby trap. (Increasing the "relevance" of their civilian victims and adding the recent experience of losing friends to the enemy, while also increasing the intensity of group support for killing.) According to one witness, Calley's company commander, Captain Medina, stated in a briefing to his men that '"our job is to go in rapidly, and to neutralize everything. To kill everything.' 'Captain Medina? Do you mean women and children, too?' 'I mean everything.'" (Moderately intense demands of a legitimate and respected authority figure.) When we look at photographs of the piles of dead women and children at My Lai it seems impossible to understand how any American could participate in such an atrocity, but it also seems impossible to believe that 65 percent of Milgram's subjects would shock someone to death in a laboratory experiment, despite the screams and pleas of the "victim," merely because an unknown obedience-demanding authority told them to. Although it is

not

an excuse for such behavior, we can at least understand how My Lai could have happened (and possibly prevent such occurrences ALL F A C T O R S C O N S I D E R E D

191

in the future) by understanding the power of the cumulative factors associated with a soldier ordered to kill by a legitimate, proximate, and respected authority, in the midst of a proximate, respected, legitimate, consenting group, predisposed by desensitization and conditioning during training and recent loss of friends, distanced from his victims by a widely accepted cultural and moral gulf, confronted with an act that would be a relevant loss to an enemy w h o has denied and frustrated other available strategies.

A veteran quoted by Dyer shows a deep understanding of the tremendous pressures many of these factors place on the "ordinary, basically decent" American soldier:

You put those same kids in the jungle for a while, get them real scared, deprive them of sleep, and let a few incidents change some of their fears to hate. Give them a sergeant who has seen too many of his men killed by booby traps and by lack of distrust, and who feels that Vietnamese are dumb, dirty, and weak, because they are not like him. Add a little mob pressure, and those nice kids who accompany us today would rape like champions. Kill, rape and steal is the name of the game.

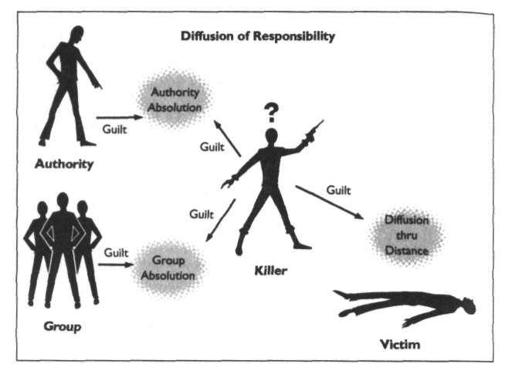

Each Man a Firing Squad

In summary, most of the factors that enable killing on the battlefield can be seen in the diffusion of responsibility that exists in an execution by firing squad. Because, in combat, each man

is

really a member of a huge firing squad. The leader gives the command and provides the demands of authority, but he does not have to actually kill. T h e firing squad provides conformity and absolution processes. Blindfolding the victim provides psychological distance.

And the knowledge of the victim's guilt provides relevance and rationalization.

The killing-enabling factors provide a powerful set of tools to bypass or overcome the soldier's resistance to killing. But as we will see in the section "Killing in Vietnam," the higher the resistance bypassed, the higher the trauma that must be overcome in the subsequent rationalization process. Killing comes with a price, and societies must learn that their soldiers will have to spend the rest

192 AN A N A T O M Y OF KILLING

of their lives living with what they have done. The research outlined in this book has permitted us to understand that, although the mechanism of the firing squad ensures killing, the psychological toll on the members of a firing squad is tremendous. In the same way, society must now begin to understand the enormity of the price and process of killing in combat. Once they do, killing will never be the same again.

S E C T I O N V

Killing and Atrocities:

"No Honor Here, No Virtue"

The basic aim of a nation at war is establishing an image of the enemy in order to distinguish as sharply as possible the act of killing from the act of murder.

— Glenn Gray

The Warriors

"Atrocity" can be defined as the killing of a noncombatant, either an erstwhile combatant w h o is no longer fighting or has given up or a civilian. But modern war, and particularly guerrilla warfare, makes such distinctions blurry.

Atrocity has always been part of war, and in order to understand war we must understand atrocity. Let us begin to understand it by examining the full spectrum of atrocity.

Chapter One

The Full Spectrum of Atrocity

We often think of Nazi atrocities in World War II as all having been committed by psychopaths or sadistic killers, but there is a fortuitous shortage of such individuals in society. In reality, the problem of distinguishing murder from killing in combat is extremely complex. If we examine atrocity as a spectrum of occurrences rather than a precisely defined type of occurrence, then perhaps we can better understand the nature of this phenomenon.

This spectrum is intended to address only individual personal kills and will leave out the indiscriminate killing of civilians caused by bombs and artillery.

Slaying the Noble Enemy

Anchoring one end of the spectrum of atrocity is the act of killing an armed enemy who is trying to kill you. This end of the spectrum is not atrocity at all, but serves as a standard against which other kinds of killing can be measured.

The enemy who fights to a "noble" death validates and affirms the killer's belief in his

own

nobility and the glory of his cause.

Thus a World War I British officer could speak admiringly to Holmes of German machine gunners who remained faithful unto death: "Topping fellows. Fight until they are killed. They gave us hell." And T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia) immortalized 196

KILLING AND A T R O C I T I E S

in prose the German units who stood firm against his Arab forces during the rout of the Turkish army in World War I: I grew proud of the enemy who had killed my brothers. They were two thousand miles from home, without hope and without guides, in conditions bad enough to break the bravest nerves. Yet their sections held together, sheering through the wrack of Turk and Arab like armoured ships, high faced and silent. When attacked they halted, took position, fired to order. There was no haste, no crying, no hesitation. They were glorious.

These are "noble kills," which place the minimum possible burden on the conscience of the killer. And thus the soldier is able to further rationalize his kill by honoring his fallen foes, thereby gaining stature and peace by virtue of the nobility of those he has slain.

Gray Areas: A m b u s h e s and Guerrilla Warfare Many kills in modern combat are ambushes and surprise attacks in which the enemy represents no immediate threat to the killer, but is killed anyway, without opportunity to surrender. Steve Banko provides an excellent example of such a kill: "They didn't k n o w I existed . . . but I sure as hell saw them. . . . This is one f- ed up way to die, I thought as I squeezed softly on the trigger."

Such a kill is by no means considered an atrocity, but it is also distinctly different from a noble kill and potentially harder for the killer to rationalize and deal with. Until this century such ambush kills were extremely rare in combat, and many civilizations partially protected themselves and their consciences and mental health by declaring such forms of warfare dishonorable.

O n e of the things that made Vietnam particularly traumatic was that due to the nature of guerrilla warfare, soldiers were often placed in situations in which the line between combatant and noncombatant was blurred:

For the tense, battle-primed GIs ordered to seal off the village, the often subtle nuances and indicators used by interrogators to identify T H E FULL S P E C T R U M OF A T R O C I T Y 197

VC from civilian, combatant from non-combatant, were a luxury they felt they could not afford. The decision, VC or not VC, often had to be reached in a split second and was compounded by the language barrier. The consequences of any ambiguity sometimes proved fatal to Vietnamese villagers. In Ben Suc, one unit of American soldiers, crouching near a road leading out of the village, were on the lookout for VC. A Vietnamese man approached their position on a bicycle. He wore black pajamas, the peasant outfit adopted by the VC. As he rode 20 yards past the point where he first came into view, a machine gun crackled some 30 yards in front of him. The man tumbled dead into a muddy ditch.

One soldier grimly commented: "That's a VC for you. He's a VC all right. That's what they wear. He was leaving town. He had to have some reason."

Maj Charles Malloy added: "What're you going to do when you spot a guy in black pajamas? Wait for him to get out his automatic weapon and start shooting? I'm telling you I'm not."

The soldiers never found out whether the Vietnamese was VC

or not. Such was the perplexity of a war in which the enemy was not a foreign force but lived and fought among the people.

— Edward Doyle

"Three Battles"

As we read the words of these men, we can place ourselves in their shoes and understand what they are saying. They were men trained to kill in a tense situation; they had no real need to justify their actions. So why did they try so hard? "That's a VC for you.

He's a VC all right. That's what they wear. He was leaving town.

He had to have some reason." It may be that what we are hearing here is someone trying desperately to justify his actions to himself.

He has been placed in a situation in which he has been forced to take these kinds of actions, maybe even make these kinds of mistakes, and he

needs

desperately to have someone tell him that what he did was right and necessary.

Sometimes it was even more difficult. For example, consider the situation that this U.S. Army helicopter pilot found himself in in Vietnam:

198

KILLING AND A T R O C I T I E S

Off to our left we could see a couple of downed Hueys [helicopters]

inside the paddy. Strangely, just as I reached the center of the hub I noticed an old lady, standing almost dead center of the hub, casually planting rice. Still zigzagging, I looked back over my shoulder at her trying to figure out what she was doing there — was she crazy or just determined not to let the war interfere with her schedule? Glancing again at the burning Hueys it dawned on me what she was doing out there and I turned back.

"Shoot that old woman, Hall," I yelled, but Hall [the door gunner], who had been busy on his own side of the chopper had not seen her before and looked at me as if I had gone crazy, so we passed her without firing and I zigzagged around the paddies, dodging sniper fire, while I filled Hall in.

"She has a 360 degree view over the trees around the villages, Hall," I yelled. "The machine gunners are watching her and when she sees Hueys coming, she faces them and they concentrate their fire over the spot. That's why so many are down around here —

she's a goddamned weathervane for them. Shoot her!"

Hall gave me a thumbs up and I turned to make another pass, but Jerry and Paul [in another helicopter] had caught on to her also and had put her down. For some reason, as I again passed our burning Hueys, I could not feel anything but relief at the old woman's death.

— D. Bray

"Prowling for POWs"

Was the woman being forced to do what she was doing? Was she truly a Vietcong sympathizer, or a victim? Were Vietcong weapons being held on her or her family?

And would anyone have done any differently than these pilots under the circumstances? Possibly. But possibly they would not have lived to tell about it if they had done differently. Certainly no one will ever prosecute these men, and most certainly they will have to live with these kinds of doubts for the rest of their lives.

Sometimes the trauma associated with these gray-area killings in modern combat can be tremendous:

T H E FULL S P E C T R U M OF A T R O C I T Y 199

Look, I don't like to kill people, but I've killed Arabs [note the unconscious dehumanizing of the enemy]. Maybe I'll tell you a story. A car came towards us, in the middle of the [Lebanese] war, without a white flag. Five minutes before another car had come, and there were four Palestinians with RPGs [rocket-propelled grenades] in it — killed three of my friends. So this new Peugeot comes towards us, and we shoot. And there was a family there —

three children. And I cried, but I couldn't take the chance. It's a real problem. . . . Children, father, mother. All the family was killed, but we couldn't take the chance.

— Gaby Bashan, Israeli reservist in Lebanon, 1982

quoted in Gwynne Dyer,

War

O n c e again, we see killing in modern warfare, in an age of guerrillas and terrorists, as increasingly moving from black and white to shades of gray. And as we continue down the atrocity spectrum, we will see a steady fade to black.

Dark Areas: Slaying the Ignoble Enemy

The close-range murder of prisoners and civilians during war is a demonstrably counterproductive action. Executing enemy prisoners stiffens the will of the enemy and makes him less likely to surrender. Yet in the heat of battle, it happens quite often.

Several of the Vietnam veterans I interviewed said, without detailed explanation, that they "never took prisoners." Often in school and training situations when it is impractical to take prisoners during operations behind enemy lines, there is an unspoken agreement that the prisoners have to be "taken care of."

But in the heat of battle it is not really all that simple. In order to fight at close range one must deny the humanity of one's enemy.

Surrender requires the opposite — that one recognize and take pity on the humanity of the enemy. A surrender in the heat of battle requires a complete, and very difficult, emotional turnaround by both parties. The enemy w h o opts to posture or fight and then dies in battle becomes a noble enemy. But if at the last minute he tries to surrender he runs a great risk of being killed immediately.

Holmes writes at length on this process:

200

KILLING AND A T R O C I T I E S

Surrendering during battle is difficult. Charles Carrington suggested, "No soldier can claim a right to 'quarter' if he fights to the extremity." T.P. Marks saw seven German machine-gunners shot. "They were defenseless, but they have chosen to make themselves so. We did not ask them to abandon their guns. They only did so when they saw that those who were not mown down were getting closer to them and the boot was now on the other foot."

Ernst Junger agreed that the defender had no moral right to surrender in these circumstances: "the defending force, after driving their bullets into the attacking one at five paces' distance, must take the consequences. A man cannot change his feelings again during the last rush with a veil of blood before his eyes. He does not want to take prisoners but to kill."

During the cavalry action at Moncel in 1914 Sergeant James Taylor of the 9th Lancers saw how difficult it was to restrain excited men. "Then there was a bit of a melee, horses neighing and a lot of yelling and shouting. . . . I remember seeing Corporal Bolte run his lance right through a dismounted German who had his hands up and thinking that it was a rather bad thing to do."

Harold Dearden, a medical officer on the Western Front, read a letter written by a young soldier to his mother. "When we jumped into their trench, mother, they all held up their hands and shouted 'Camerad, Camerad' and that means 'I give in' in their language. But they had to have it, mother. I think that is all from your loving Albert ."

. . . No soldier who fights until his enemy is at close small-arms range, in any war, has more than perhaps a fifty-fifty chance of being granted quarter. If he stands up to surrender he risks being shot with the time-honoured comment, 'Too late, chum.' If he lies low, he will fall victim to the grenades of the mopping-up party, in no mood to take chances.

Yet Holmes concludes that the consistently remarkable thing in such circumstances is not how many soldiers are killed while trying to surrender, but h o w few. Even under this kind of provocation, the general resistance to killing runs true.

T H E FULL S P E C T R U M O F A T R O C I T Y

201

Surrender-executions are clearly wrong and counterproductive to a force that has dedicated itself to fighting in a fashion that the nation and the soldiers can live with after battle. They are, however, completed in the heat of battle and are rarely prosecuted. It is only the individual soldier w h o must hold himself accountable for his actions most of the time.

Executions in cold blood are another matter entirely.

Black Areas: Executions

"Execution" is defined here as the close-range killing of a noncombatant (civilian or P O W ) w h o represents no significant or immediate military or personal threat to the killer. The effect of such kills on the killer is intensely traumatic, since the killer has limited internal motivation to kill the victim and kills almost entirely out of external motivations. T h e close range of the kill severely hampers the killer in his attempts to deny the humanity of the victim and severely hampers denial of personal responsibility for the kill.

Jim Morris is an e x - G r e e n Beret and a Vietnam veteran turned writer. Here he interviews an Australian veteran of the Malaysian counterinsurgency w h o is trying to live with the memory of an execution. His story is entitled "Killers in Retirement: ' N o Heroes, No Villains, Just M a t e s . ' "

This time we leaned against a wall on the opposite side of the room. He leaned forward, speaking softly and earnestly. This time there was no pretense. Here was a man baring his soul.

"We attacked a terrorist prison camp, and took a woman prisoner. She must have been high up in the party. She wore the tabs of a commissar. I'd already told my men we took no prisoners, but I'd never killed a woman. 'She must die quickly. We must leave!' my sergeant said.

"Oh god, I was sweatin'," Harry went on. "She was magnificent.

'What's the matter, Mister Ballentine?' she asked. 'You're sweatin'.'

"'Not for you,' I said. 'It's a malaria recurrence.' I gave my pistol to my sergeant, but he just shook his head. . . . None of them would do it, and if I didn't I'd never be able to control that unit again.

202

KILLING AND A T R O C I T I E S

" 'You're sweatin', Mr. Ballentine,' she said again.