On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (2 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

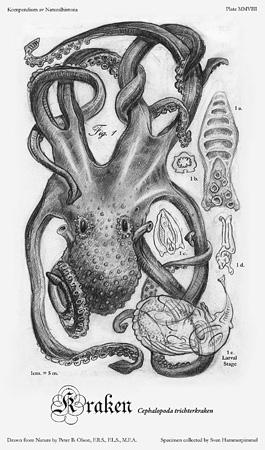

The Kraken is a mythical sea monster that has troubled sailors’ dreams for centuries. The legend may be based on glimpses of giant squids or abnormally large octopi. Drawing of the Kraken, complete with faux scientific nomenclature, by artist Peter Olson © 2008. Reprinted by kind permission of the artist.

www.peterolsonbirds.com

.

When the first two crazy people, I mean

scientists

, descended a quarter of a mile into the ocean in a crude bathysphere, they found unimaginable creatures. Off a Bermudan island in 1930 William Beebe and Otis Barton witnessed swarms of bioluminescent creatures—transparent eels, shrimp, and nightmarish fish—and giant shadowy figures looming just outside the range of their spotlight. They could descend only a fraction of the actual

sea depth, but when asked to describe the receding waters below them, Beebe said that the abyss “looked like the black pit-mouth of hell itself.”

2

A survey of popular culture indicates that I am not alone in my fear of sea monsters. Television, movies, and video games are rife with neck-tensing narratives about underwater peril. The literature and imagery of high culture, too, have long been fascinated with the idea of watery fiends.

3

But there may be deeper reasons, below the stratum of culture, for the ubiquitous sea monster phobia. Evolution may have built this into our species over the span of many prehistoric millennia. Fear of murky water may have been a good survival strategy for ancestors who regularly fell victim to real predators; trepidation at water’s edge may have been just the thing that helped some hominids to leave progeny. This is speculative, but it is consistent with basic Darwinian assumptions about the evolution of instincts.

In a telling passage from

The Descent of Man

, Darwin scandalously compares the intellects and emotions of humans and animals.

4

He tells several stories of his experiments at the Zoological Gardens, in particular his research at the monkey house. Darwin knew that monkeys had an “instinctive dread” of snakes, so he took a dead, stuffed, and coiled-up snake down to the monkey house. “The excitement thus caused was one of the most curious spectacles which I ever beheld,” he wrote. A stuffed snake was too horrifying and the monkeys stayed far away from it, but a dead fish, a mouse, and even a live turtle eventually drew the monkeys in and they displayed no fear in handling them. Pushing the experiment further, Darwin placed a live snake in a bag and put this inside the cage. “One of the monkeys immediately approached, cautiously opened the bag a little, peeped in, and instantly dashed away.” But then, in a human-like act of curiosity, “monkey after monkey, with head raised high and turned on one side, could not resist taking a momentary peep into the upright bag, at the dreadful object lying quietly at the bottom.”

5

To monkeys, snakes are monstrously threatening and so their instincts err on the side of caution. In a state of nature many snakes are real threats; from an evolutionary point of view, any monkeys that happened to be extra timid around them probably lived to procreate another day. One might say that monkeys have an

emotional caricature

of snakes in their instinctual vocabulary. The monsters of our human imagination may be similar caricatures, originally built on legitimate threats but eventually spiraling into the autonomous elaborations that only big brains can produce. In my brain, the piranha becomes the Loch Ness Monster.

Arachnophobia, or fear of spiders, seems to be a universal human dread, especially in children. The biologist Tim Flannery asks, “Why do so many

of us react so strongly, and with such primal fear, to spiders? The world is full of far more dangerous creatures such as stinging jellyfish, stonefish, and blue ringed octopi that—by comparison—appear to barely worry most people.”

6

Flannery speculates that a Darwinian story connects human arachnophobia to our African prehistory. Because

Homo sapiens

emerged in Africa, he wonders whether a species or genus of spider could have been present as an environmental pressure. Africa is the place where the human mind acquired many of its useful instincts. If humans evolved in an environment with venomous spiders, a phobia could have been advantageous for human survival and could be expected to gain greater frequency in the larger human population. The six-eyed sand spider of western and southern Africa actually fits that speculation very well. It is a crab-like spider that hides in the sand and leaps out to capture prey; its venom is extremely harmful to children. One can see how a fear of spiders would have been highly advantageous in this context. Our contemporary arachnophobia may be a leftover from our prehistory on the savanna.

7

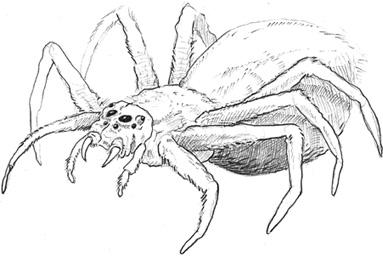

Many monster archetypes seem to tap into widespread arachnophobia. Some evolutionary psychologists believe that spider and snake phobias are the result of natural selection. Pencil drawing by Stephen T. Asma © 2008.

In recent cognitive science debates, fears of snakes, spiders, and other creatures have been held up as examples of preset mental circuits in the human brain.

8

Though it is a controversial idea, a growing number of theorists argue that our brains come hard-wired with some belief content, such

as “snakes = bad.” The fact that phobias seem so resistant to revision in light of new experiences suggests that they are closed information systems. Even after a phobic person is told that a snake is not poisonous or witnesses the removal of the venom ducts, he or she still dreads handling the reptile. The phobia stays like a stubborn piece of antiquated furniture in the architecture of the mind.

9

Perhaps monsters are also part of our furnished mind. As cultural and psychological realities, monsters certainly seem unwilling to go away, no matter how much light we shine in their direction.

More important for my thesis, however, is the wonderfully ambivalent tension in Darwin’s zoo monkeys. The monkey cannot fully confront the snake, but he cannot leave it alone either. He is repelled

and

attracted. Of course, we are just like him; we cannot “resist taking a momentary peep…at the dreadful object lying quietly at the bottom.”

While perusing the disturbing deformed specimens at the Hunterian Museum in London,

10

I found myself standing beside a young boy and his mother. We were all staring at a display case that contained a series of tragically malformed babies floating in large jars of alcohol.

“Oh my God!” the boy cried out. He repeatedly shrieked as he moved around the frightening display cases. The Hunterian Museum is a treasure trove of macabre specimens, some dating back to the mid-1700s. The collection, like the one in the American Mutter Museum in Philadelphia, is an unsettling compendium of the ways Nature can go wrong.

“Oh Lord, I can’t believe it!” the boy gasped in his thick north England accent. He was moving into the pathology section of the museum now, and he was being drawn into the morose magic of Hunter’s collection. As he stared intensely at a fetus with two fused heads, his mother suddenly turned to him and asked, “Is this disturbing to you, William?” He didn’t look away from the cases, but responded, “God, yes. Very.”

“Shall we go, then, dear?”

“No,” he shot back, “absolutely not.”

WHEN MY SON AND I LIVED IN CHINA

he demonstrated the same ambivalent human impulse. In China today, as in other parts of the developing world, it is still possible to see adults who suffer from birth defects that would have been routinely remedied in the West by early surgeries or procedures. Lack of decent health care has doomed many poor people to lifelong struggles with otherwise easily curable maladies.

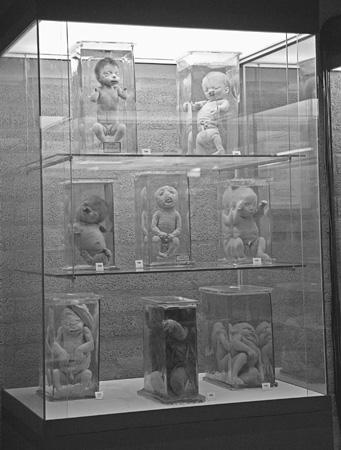

Similar to those of the Hunterian and Mutter Museums, here is a vitrine of teratological birth defects from the Vrolik Museum. Many of us find them difficult to look at, and yet it is difficult to look away. Photo by Joanna Ebenstein © 2008. Reprinted by kind permission of the artist and the Vrolik Museum, University of Amsterdam.

In our neighborhood, an undeveloped suburb of Shanghai, my three-year-old son and I walked to school every day and stopped to drop a few coins in the begging cup of a hydrocephalic woman. Her head was swollen to the size of a large beach ball, perhaps three times normal size, and she rested it sideways on her shoulder as she sat on the sidewalk. My son was frightened of her, but he staunchly resisted my attempts to avoid her and insisted every day that we stop to say “Ni hao” to the “big head lady,” as he referred to her.

These are examples of what we’ve all experienced at some time or other: the simultaneous lure and repulsion of the abnormal or extraordinary being. This duality is an important aspect of our notion of monsters too.

Monster

is a flexible, multiuse concept. Until quite recently it applied to unfortunate souls like the hydrocephalic woman. During the nineteenth century “freak shows” and “monster spectacles” were common; such exploitation of genetically and developmentally disabled people must be one of the lowest points on the ethical meter of our civilization.

11

We have moved away from this particular pejorative use of

monster

, yet we still employ the term and concept to apply to

inhuman

creatures of every stripe, even if they come from our own species. The concept of the monster has evolved to become a moral term in addition to a biological and theological term. We live in an age, for example, in which recent memory can recall many sadistic political monsters.

In 2003 I lived within walking distance of the infamous Security Prison S21, a torture compound in Cambodia. It took months for me to get up the nerve to visit. Pierrot, the Swiss owner of my guesthouse, told me that he still refused to go after ten years in Phnom Penh. “You will not get me in that place, mon ami.” He explained, “It is the maker of bad dreams, and I wish to sleep well.” Like Pierrot, I didn’t want to go to S21 either. But S21 was a place of monsters, real monsters and real victims, and I could not altogether leave it alone.

Over and over again one hears the same story of torturers—whether Nazis, Pinochet lackeys, American soldiers at Abu Ghraib, or Khmer Rouge teenagers at S21—the story that they were just “following orders.” But before we dismiss these people as demons that bear no resemblance to us, we should remember Stanley Milgram’s famous experiment on the psychology of obedience to authority, in which average Americans were made to believe they were shocking other average Americans with lethal doses of electricity simply because a man in a white lab coat insisted that they do so.

12

Most people who hear about Milgram’s study ask themselves what they would do as a test subject. Or we wonder how we would respond if we were told that prisoner

X

is an enemy of freedom and that we must pressure him to give up information about an imminent terrorist plan. Or worse yet, we wonder what we would do if someone held a gun to our head and told us to cut someone else’s throat. That’s what happened at S21, over and over again. If we were in that situation, would we become monsters? Or does such heinous action require freewill agency in order to qualify the perpetrator as monstrous?