Read One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution Online

Authors: Nancy Stout

One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution (44 page)

At eleven, Lydia had an anxiety attack and said she couldn’t spend the night in her brother-in-law’s house. She was too afraid. She wanted to go to 451 Rita, the address of a 26th of July safe house in a nearby Juanello neighborhood. Reinaldo Cruz (who had stayed to guard her) called Gustavo Mas, who informed him that the house on Rita was off-limits. It wasn’t safe, and no one could use it, on movement orders. Finally, they settled on going to a bar called the Catacombs, on Virgen del Camino, where they could hang out for the rest of the night.

El Joyero (The Jeweler), a well-known police informer, was assassinated that night and police started arresting anyone they could. Soon Lydia, Clodomira, Reinaldo Cruz, and Alberto Álvarez

left the bar, frightened by the police activity. They went to 451 Rita just before dawn. Two boys (Onelio Dampier and Leonardo Valdes), on the run, showed up there and Lydia and the others let them in. It was a bad move; in the next hours—it was now September 12—Ventura’s men arrested José Antonio Pinon, called “Popeye,” who, under torture, gave them information including the address of this house. The police took him back to Rita, where Reinaldo Cruz recognized Popeye’s voice, opened the door, and was killed immediately by rounds from a machine gun. Everybody in the apartment was armed. They killed four policemen. Lydia got hit with a bullet in one buttock, and Clodomira alone came out unharmed. Reinaldo, Alberto, and the two boys were killed. The two women were taken to the 14th Precinct police station in Juanelo and kept there for the rest of the day.

Lydia could barely stand, and one of the police gave her a shove where she’d received the bullet but she didn’t cry out. Infuriated, he picked up his club and hit her in the back of the neck, knocking her unconscious. Clodomira turned on the police, biting, punching, and scratching the policeman who’d hit Lydia. Both women were taken to the La Chorrera 9th Precinct, located near a fifteenth-century tower and the sea wall.

The rest of this account was given by one of Ventura’s policemen, called Carratala, who was interviewed in his cell in La Cabaña Fortress after the January 1959 victory. Carratala stated that Ventura, chief of police, admitted that his “boys had gone a little too far” and recalled that Clodo had bitten him on the shoulder (the report states that he showed his scar to the interviewer). “She was a real beast, that one.” He then described how Lydia and Clodomira were placed in bags by 9th Precinct policemen who then filled these bags with sand, lowered them into the sea near La Chorrera and would then pull them out again. The third time Lydia was submerged she died; they gave Clodomira a

coup de grâce

. Then their bodies were thrown into the sea.

This account was verified later, with only slightly different details, by one of the prisoners captured at the Bay of Pigs. A former member of the police (Calvino) said that Laurent, in charge of the precinct, had tried to get information from the women that “the others had not” by taking them in a boat offshore, where they were put in sacks into which sand was poured; and that Laurent

had them dunked in the water and brought up again. Lydia, “whose eyes were almost out of their sockets,” had died right away but the “younger and tougher” one had resisted.

When Lydia didn’t show up the next morning at the meeting spot, Griselda immediately got in touch with Monsignor Raúl del Valle, secretary to the Cardinal of Havana. He made arrangements for Griselda’s M-26 partner, Ismael Suarez, to go to the morgue, where he found Reinaldo Cruz’s body. He counted the number of bullet holes in his body—52 from the waist up—saw the bodies of the other three men, noticed that their hair was standing straight up since the bodies had been pulled by the feet down the stairs of the apartment building and the hair, already stiff with blood, dried upright. Suarez didn’t find Lydia or Clodo, so Monsignor de Valle made arrangements for Suarez to go to the cemetery. So many bodies had arrived that morning that some had already been covered, but the grave diggers were able to confirm that no one fit Lydia’s or Clodo’s description. Other reports say they had been sighted in a police car—which is possible—being given “a macabre tour of the streets,” as Che described it, to force them to give up information. Their deaths are usually dated September 17, but if you believe the prisoners, they died as early as September 13, 1958. Over the years, Celia’s staff at the Office of Historical Affairs collected evidence. A short biography of Lydia was published in 1974 as a pamphlet, which states that there are many versions of how she and Clodo were murdered and none is certain. The writers of this pamphlet were reluctant to quote—as I have done—anything from the mouths of

batistianos

, particularly policemen, or from a prisoner.

29. N

OVEMBER

1958

The Triumph

CELIA LEFT THE

COMANDANCIA

with Fidel and did not return there for the rest of the war. Neither seems to have regretted trading paradise for the battlefield. Fidel was about to command his final battle against Batista’s forces.

They traveled slowly, stopping at the rebel army’s training school in Minas de Bueycito first, and on the 17th were approaching Guisa (inland and to the northeast of Pico Turquino). In that town the army maintained a significant garrison, which the rebels were ready to engage. On the 20th, Celia left Fidel to start receiving and assigning recruits, at a place called Mon Corona Farm. She had gone ahead to set up his field headquarters and chose the hamlet of Santa Barbara, just west of Guisa.

The rebel army had grown enormously in the final months of 1958, and, at Guisa, Fidel deployed two of his all-women squadrons from the Mariana Grajales unit trained at the

Comandancia

. He’d be using five hundred troops, a major force for the rebel army, but they were outnumbered ten to one, and most of them were new to combat. But they had spirit. “The Battle of Guisa was one of those events that proved nothing was impossible for that small army,” Fidel said in 2000, when he commemorated the battle’s 42nd anniversary. The army’s 5,000 well-trained, well-armed soldiers were supported by air power and tanks. But Batista’s troops were low on morale.

The Battle of Guisa, a bloody engagement and not easily won, was waged from November 20 to 30.

THE ARMY GARRISON WAS LOCATED

right on the main east-west highway. By taking the Guisa garrison, Fidel wanted to demonstrate the vulnerability of the army’s headquarters, which was just down that highway, in Bayamo. Fidel’s troops didn’t attack the garrison directly; they ambushed the army’s reinforcements trying to reach it, and did so with small contingents posted along the route. Their most useful point of defense was a hill—not a large nor a high one—with just enough elevation to see Batista’s convoys as they came up the road. The rebel army lost and recaptured this hill many times during ten days of battle, but used it to strategic advantage; at one point, so the story goes, every fighter in one of the little rebel bands managed to fire his or her rifle in unison, and they brought down a plane. At the peak of combat, the rebels surrounded an entire enemy battalion loaded into fourteen trucks and protected by two light tanks, simply by attacking from every direction.

“We have a strong line of defense between Bayamo and Guisa,” Fidel wrote to Ricardo Martínez (a letter he treasures) who had stayed at the

Comandancia

. “It’s like Jiguani, but at the doors of Bayamo. Here, our fight is against tanks; one has been overturned. The veterans aren’t with me,” he added, referring to former battles when Che, Guillermo García, and Crescencio Perez had been at his flank or elsewhere nearby. Now his most seasoned comrades were leading their own troops, in other parts of the country. “But the troops are behaving well. Cordolun has turned into a lion. He has opened more than 200 trenches. We have picks and shovels all over the place. The people are good. Everybody is anticipating being able to buy something, [because] in Guisa there are many goodies. An embrace for all of you, Fidel Castro.” He apparently handed the letter to Celia who closes with “A hug, Celia Sánchez.”

At Guisa, Captain Baulio Coroneaux, called “Cordolun,” operated the rebels’ one and only .50-caliber machine gun, apparently with great effect, until he was killed by a precision shot from a tank. The troops, Fidel noted in 2000, were “children of workers and farmers; most of them could not even read or write. And in their training, they had hardly made any real shots. They had learned and practiced shooting theoretically.” His reminiscence recalls the early 26th of July actions, when Frank País drilled his men for the Battle of Santiago with “no bullets” exercises.

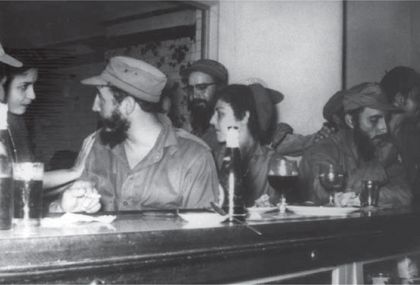

The evening of December 31, 1958, Fidel, Celia, and Pedro Miret sit at a bar in the city of Palma Soriano, waiting to negotiate with the Cuban army and end the war. Celia’s stalwart assistant, Felipe Guerra Matos, stands behind her. They watch an admirer who has come to speak to Fidel. (

Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos

)

The heaviest fighting came in the last three days, when the army sent in B-26s and F-47s, from bases in Havana and Camaguey, to bomb the area and rescue their battalion. To create a “zone” for the government forces’ escape route, the army unleashed thirty hours’ air support, showering the rebels with bombs. But the rebel army, in Cordolun’s trenches, held out.

To rescue the besieged battalion, in the end, the army was forced to abandon the garrison. The rebels had their victory, and Bayamo lay within their sights.

Celia’s two younger sisters, Acacia and Griselda, had traveled to the locale to experience a battle firsthand. Shortly before the intensive bombing started, Griselda, who hated noise, took refuge in a cave outside the city. Celia, even as the battle raged, sent a note to them, remarking that the army was shooting as if it were the end of the world. The Gironas, in Havana, received a postcard

from Griselda. She wrote that she was vacationing in lovely Guisa, and: “Wish you were here.”

CELIA AND FIDEL THEN TRAVELED EAST

. On December 2, 1958, they stopped in Charco Redondo, where Celia set up another field headquarters. The date would have been significant for her: the second anniversary of her escape from the SIM in Campechuela and the bar La Rosa. Now, with several victories behind them, she and Fidel waited for Camilo and Che to conclude their long march across the island, heading for Havana. By December 20, Fidel and Celia had moved onto a sugar estate called “America.” They left to spend Christmas with Fidel’s oldest brother, Ramon, a farmer who sat out the war, returning to the America sugar mill on the 28th. There they rendezvoused with one of Batista’s generals, Eulogio Cantillo, to discuss ways to bring the war to an end. While Fidel and Cantillo talked, Ricardo Martínez says that he and Celia waited in a room filled with sugar-processing machinery. Fidel emerged confident that he and the general had come to an agreement, assured that Batista would remain in Cuba.

On the final day of the year, they drove to Palma Soriano, up in the mountains, and the last town of any size on the way to Santiago. There they learned of Batista’s escape. Fidel was furious. They went to the local station (an affiliate of Radio Progresso), from which Fidel broadcast an appeal to all citizens of Cuba, imploring people not to take the law into their own hands. Following the broadcast, he ordered an advance on Santiago. Simultaneously, across the nation, members of the 26th of July Movement, the Revolutionary Directorate, and other anti-Batista groups occupied police stations. At the news that Batista had fled, cheering crowds came out into the streets. Unpopular members of the police and military were assassinated; some were jailed to await trial; others quickly got out of Cuba. Historians consistently remark on the fact that there was little violence.

When Fidel met in a final parley with the army’s commanders, Celia took part. On January 1, 1959, at El Escandel, an outpost northeast of Santiago (now within the National Park Gran Piedra), Colonel José Rego Rubido, regimental chief, surrendered Santiago de Cuba and its forces to the rebel army.