One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution (60 page)

Read One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution Online

Authors: Nancy Stout

Flávia had explained what happened when I talked to her in 1999. “Celia called me. She said, ‘I’m on my way to Calixto García. Something is happening to me. I can’t breathe. The air is missing from my system.’ When I arrived, she was already there; they’d taken an x-ray and had processed it. There was a tumor in one lung. The x-rays disappeared, but I saw it, and Celia saw it, too. . . . We wanted to see what the x-ray showed. The next day, when I got to Celia’s home, I found Dr. Selman, a very special doctor, Fidel’s, one of the most important doctors in Cuba. She sat down with us, Acacia and me, and told us that Dr. Selman told her that she ought to be operated on that day, if she were willing.”

“They took out one of her lungs,” Alicia explained. “After the operation, they told her that they had removed the lung because there were nodals with aspergillus fungi. This is a fungus that can be found in moist places.”

STORIES CIRCULATE THAT CELIA’S LUNGS

were contaminated by a fungus carried through letters from Africa. And Celia herself sparked this, because she told Flávia, “My house has to be cleaned up, and I must protect myself. I open up all the mail that comes from everywhere.” The doctor had mentioned this contamination

from an African source as possibility, according to Flávia. “They cleaned up the house,” Flávia continued. “They painted. Everything was ready in a month or so, and she was allowed to go back to the house . . . She started constructing a hotel she was interested in.”

I thought this story about the mail so bizarre that I wanted to speak to a doctor about it, and a friend invited me to meet Dr. Isolina Pacheco who confirmed the story regarding this diagnosis.

Alicia, speaking in 2006, stated the situation explicitly: “The doctors didn’t mention that they saw the spot on her lung. This led to everything else. We later found out that once they saw the x-ray, they knew she had cancer, but didn’t mention it. We all knew afterward. They didn’t inform her it was cancer. They just said they would operate. Two authorities were present. . . . It was a complete lie. She had no radiation therapy, no drugs, no chemotherapy. They worked out the lie so well that the plaster was removed from the whole building, closet doors were taken off, windows enlarged for greater ventilation. Miriam Manduley was moved out of her apartment while this was done. They tested. It was all a montage.” But there is one mitigating factor that surfaced in this discussion. A few moments later, Alicia, with real sadness, admitted: “She was aware, I feel, that she’d not been told the truth.”

Flávia died in 2003. I looked again at my 1999 interview with her. She’d said: “Her clinical history was kept somewhere, it was updated, but it was kept confidential. She knew where it was. Celia had a feeling that she hadn’t been told the truth. But the whole family believed the story of the fungus.”

Migdalia Novo, Celia’s private nurse, was present at the operation. She came to the Office of Historical Affairs for an interview in 2007. When I asked her about the fungus and whether it had been the source of Celia’s health problems, she answered, “No.” She continued: “When she was operated on, in Cuba, we weren’t accustomed to be told, to your face, the diagnosis. It was difficult to explain to her what she had. Her internist, in a meeting with the surgeon and another internist, decided to tell her a little white lie. They told her it was a fungus named aspergillus. A fungus she never had. Her bedroom in the apartment was humid, and this fungus originates in humid places—like caves. The internist said to me: ‘We need your cooperation once again. You

are going to the apartment. You are going to take samples. We are going to inform her that the aspergillus fungus exists there.’ We told her that this aspergillus is what she had, but it was a white lie.” I asked if Cuban doctors today tell their patients if it is cancer. She replied, “Now, yes. My husband suffered from heart problems and they spoke of it openly. It was just this particular illness.” I interjected, “You mean cancer? But Celia hated to be lied to.” To that, Migdalia replied: “That is true. But in my years as a nurse, you can help the patient psychologically. They won’t feel anguish. What hit Celia strongly, and what she felt most, was that she had so much still to accomplish. So, if there is a person you are treating, and you state this [honest diagnosis], you have to be careful. She knew what she had. When speaking with certain people, she would say: I know what my diagnosis is. Celia never actually believed she had this fungus.” Novo was repeating an age-old argument and a view commonly held into the 1970s.

“Wasn’t she angry with her doctors?” I asked Novo. She replied, “She would call certain people and tell them that she had been lied to.”

“Good for her,” I replied.

Not to be silenced by my comments, Novo continued quietly, “Yes. She didn’t want to be lied to. She was a doctor’s daughter. The illness was in the family.”

She could live with that knowledge, was fully aware that her father and uncle had died of cancer, and that she was dying. But being lied to? She must have made a mental compromise. To my best knowledge, her surgeon, Dr. Eugenio Selman, and internist, Cuco Rodríguez de la Vega, Fidel’s doctors, were still alive in 2012.

What part did Fidel play? The family children, Sergio and Pepin Sánchez and Raysa Bofill, think Fidel made decisions for Celia because that is what she wanted.

41. S

EPTEMBER

–D

ECEMBER

1979

Two World Meetings and a Wedding

THOUGH SHE WAS ILL

, Celia took on one last significant project: overseeing the design and construction of a convention center to host a summit conference of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) to be held in Havana in September of 1979. Fidel had been named the president of that organization and Cuba would be the host of its big gathering.

The Convention Palace in Havana is a large white building that sits on the edge of a woods in Cubanacan, and was inaugurated in late August 1979. Sixty heads of state and several thousand delegates attended the conference, including Yugoslavia’s Marshal Tito, Palestine’s Yasser Arafat, and Vietnam’s Pham Van Dong. They walked a red carpet into the building to be greeted by the Cuban head of government. Fidel was at the pinnacle of his power and had come a long way since Celia had helped him host dignitaries of non-aligned nations at the Hotel Theresa in 1962.

For this conference, Celia had prepared—still insisting on doing most things herself—houses for the guests, converting confiscated residences in Laganilla and Cubanacan: refurbishing the carpets and furniture, hanging Cuban art on the walls. She had started in May 1979, and readied 132 protocol houses throughout the summer. In one, she became so ill that she could not leave, and had to go to bed there. Flávia chose this incident

to illustrate the beginning of the end of Celia’s life. “This was something she never did. Not in a room that was unfamiliar to her, not at an embassy house. And she asked that nobody call her, because she was feeling so ill.”

Celia was not quite sixty years old. Pictures taken in 1979 show that her face was lined, the skin somewhat slack, but her eyes still glittered, and her gaze remained serene. In the mid-1970s, Celia had had a face-lift (psychoanalysis and plastic surgery are part of Cuba’s idea of mental health), and several photographs show Celia with taut skin, long loose hair, wearing dozens of Mexican necklaces over a drawstring-gathered peasant blouse. Although completely uncharacteristic of the way she usually looked, these images reflect this one last willful attempt to look her best.

Between May and September, she developed a cough (although some people make a point of saying she didn’t cough) and was attending Saturday classes at the Nico Lopez School. It was her final year of study. Two students in her class say that she not only coughed, but had started smoking Cuba’s cheapest, harshest cigarettes. The evolving clinical history, not surprisingly, showed that her lymph nodes were inflamed.

BACK FROM ANGOLA

, Tony decided to get married. He didn’t want to disturb Celia and made all the arrangements. “I just told her one day that I was going to get married.” In Cuba, the state provides the wedding ceremony, pays for a few nights in a hotel, and provides a cake and refreshments for a reception. He set the date, booked a room in the Havana Libre Hotel himself. He stressed to Celia that he’d taken care of everything, and Celia said, “I am going to help you.” And he assured her that he had money. “It’s not about money,” she replied. “I’m going to help in other ways.”

She asked the lawyer at the Palace of the Revolution to perform the ceremony, found a place nearby, on 12th and 17th, hired a photographer, and had a special wedding cake delivered. “She had a suit made for me, a wonderful suit, and a dress for my wife. She had Cuco [the dressmaker, head of the Verano workshop] make it.” The wedding took place around nine at night. Celia attended. “The party lasted until five in the morning. When I was leaving for the hotel, she came over and asked me where I was going and I told her the Habana Libre, for my assigned honeymoon. And she

said, ‘No. No. Go to the Marazul. I’m giving you a present of 15 days there, at the beach. I’ve already paid for it. Go.”

IN SEPTEMBER, SHE TRAVELED

to New York to attend a meeting of the General Assembly of the United Nations and to give a party at the Cuban Mission, hosted by Fidel. She brought all the staff she needed; in fact, she brought everything, even salt and water. This reflected the level of paranoia—or vigilance—to which U.S. aggression against the Revolution had driven the Cubans. The Cordova-Caignet team was called upon to plan and produce the party. Maria Victoria Caignet says that giving government receptions had become routine by then, and as usual, they gave the party an entirely Cuban theme. Everything was Cuban, from the dinnerware to the menu. Caignet led me to shelves and cupboards in her apartment to show me a sample of each item. Glasses—sets for cocktails, wine, beer and water, from the glass-blowing workshop. They used Cuban sand, which makes the glass come out green, and blown the glasses into wooden molds. Most were straight-sided goblets with a little pedestal.

Platters and serving dishes were kiln-fired from red clay, a vibrant, fiery shade found in tobacco fields. Serving platters, carved from the most precious woods of the Sierra Maestra, had been fitted out with simple rope handles. Buffet plates, eight inches in diameter, were made of all kinds of wood, some light, some dark. Serving spoons were wood, carved in one of Celia’s workshops. Mats, woven from fine grasses in Taino Indian tradition, and napkins cut from colorful textiles that had been woven, printed, and dyed in Cuba. All the food was imported from eastern Cuba, and from Oriente came an indigenous flatbread made by pounding cassava root. Meat and fish and vegetables were packed in ice, and transported to New York.

The meal started with rum cocktails. “There was a small bar, but mostly the cocktails were passed on trays, metal trays we also took along. We took rum, we took everything: cigars, even the salt. The only things we bought were flowers and plants. We took wine, Socialist in origin. The wine was from Chile.” Evidently exported before the military coup of 1973. “The silverware was metal, made in Europe. We always bought it from Sweden or Denmark.” They took cooks from the palace, and waiters. “They wore white guayaberas. There were eight or ten of these men.” And lots of security, Caignet says, in addition to the NYPD. “Three to four hundred people attended: Africans, Europeans, independents. Not so many Latin Americans [were friends of Cuba] at that time.”

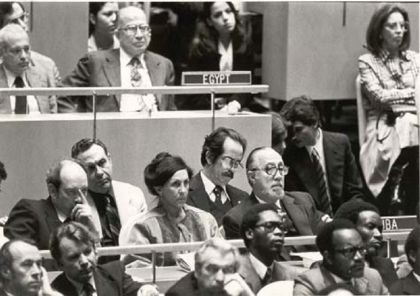

In September 1979, Celia traveled to New York to attend a meeting of the General Assembly of the United Nations and to organize a party at the Cuban Mission, hosted by Fidel. She brought all the staff she needed; in fact, she brought everything, even salt and drinking water. This was not mere scrupulous attention to detail, but a reflection of the level of paranoia—or vigilance—to which U.S. aggression against the Revolution had driven the Cuban government. (

Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos

)

After the meal, coffee was passed around. “We had a special tray with little holes in the bottom, because for cups we used

guiras

, which come from a tree.

Guira

is the same shell used to make maracas. We used very little ones cut in two, the outside is polished, with some simple designs cut in them—filled with black, sweetened coffee.”

Celia attended the arduous General Assembly meetings. Back home, the Cuban people seemed to know that she was dying—not officially, but by a very efficient grapevine that exists in the eastern section of the country, where everyone was particularly fond of Celia Sánchez. Marisela Reiners, a Spanish professor at the University of Havana, grew up in Santiago and described her parents’ concern. They took turns sitting in front of the television throughout the entire United Nations meeting (Cuba broadcast the sessions gavel-to-gavel) just to catch a glimpse of Celia and assess the state of her health. Her appearance, during that week, was widely discussed throughout Santiago, Manzanillo, Media Luna, Campechuela, Pilón, and Bayamo.