One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America (11 page)

Read One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America Online

Authors: Kevin M. Kruse

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Religion, #Politics, #Business, #Sociology, #United States

After their visit, reporters pressed Graham's group to divulge details while a row of photographers shouted at them to kneel down for a photo on the White House lawn. To their later regret, they agreed to both requests. In sharing details with the press and posing for the picture, Graham had made a significant, if innocent, mistake. The president now viewed the preacher with suspicion, dismissing him as “one of those counterfeits” only interested in “getting his name in the paper.” Feeling used and furious as a result, Truman instructed his staff that Graham would never be welcome at the White House again as long as he was president, a decision leaked to the public by political columnist Drew Pearson. Graham continued to send unrequited letters to Truman, but he sensed that he had overstepped his bounds. “It began to dawn on me a few days later,” he wrote, “how we had abused the privilege of seeing the president. National coverage of our visit was definitely not to our advantage.”

30

While Graham was dismayed at how the meeting went, Truman's coldness toward him made it much easier for him to express his true

feelings about the president. “Harry is doing the best he can,” he joked at one revival. “The trouble is that he just can't do any better.” In a more serious tone, Graham soon ventured to criticize the administration from the pulpit. In January 1951, he warned that “the vultures are now encircling our debt-ridden inflationary economy with its fifteen-year record of deficit finance and with its staggering national debt, to close in for the kill.” He chided Democrats for wasting money on the welfare state at home and the Marshall Plan abroad. “The whole Western world is begging for more dollars,” he noted that fall, but “the barrel is almost empty. When it is emptyâwhat then?” He insisted that the poor in other nations, like those in his own, needed no government assistance. “Their greatest need is not more money, food, or even medicine; it is Christ,” he said. “Give them the Gospel of love and grace first and they will clean themselves up, educate themselves, and better their economic conditions.”

31

In January 1952, Graham returned to Washington, determined to make a better impression than he had two years before. This time, his team planned a five-week revival in the capital. The focus of the Washington crusade was a series of regular meetings at the National Guard Armory, but it also featured daily local broadcasts on both radio and television, weekly coast-to-coast broadcasts of his

Hour of Decision

TV show on Sunday nights, and a network of prayer services coordinated over the radio. Graham led prayer meetings all over town, including daily sessions in the Pentagon auditorium. On Monday mornings, he held “Pastor's Workshops” with local clergymen; on Tuesdays, there were luncheons at the Hotel Statler to discuss religion with “the men who have so much a part in shaping the destiny of the Capital of Western Civilization: the business men of Washington.” Graham courted congressmen as well, of course. When he first announced the crusade, he did so with a senator and ten representatives standing alongside him. Abraham Vereide, who had helped conceive the Washington crusade and served on its executive committee, invited members of his congressional prayer breakfast groups to attend a special luncheon with Graham for “a discussion on âThe Choice Before Us.'” Despite the rift between them, Graham hoped to convince President Truman to attend the first service and, if possible, offer some opening remarks. Truman steered clear. A staff memo noted the president “said very decisively that he did not wish to endorse Billy Graham's Washington

revival, and particularly, he said, he did not want to receive him at the White House. You remember what a show of himself Billy Graham made the last time he was here. The President does not want it repeated.”

32

As the Washington crusade began in January 1952, Graham made clear his intent to influence national politics. If Congress and the White House “would take the lead in a spiritual and moral awakening,” he said, “it would affect the country more than anything in a long time.” Those who supported the revival were given cards to place in their Bibles, reminding them to pray daily “for the message of [the] Crusade to reach into every Government office, that many in Government will be won for Christ.” Although the president remained aloof, many congressmen embraced Graham. Virginia senator A. Willis Robertson secured unanimous Senate approval of the crusade, as well as a prayer that “God may guide and protect our nation and preserve the peace of the world.” Several congressmen took roles in the revival, including four who regularly served as ushers. Many more attended, with roughly one-third of all senators and one-fourth of all representatives requesting special allotments of seats to the Armory services. “As near as I can tell,” Graham bragged to a reporter, “we averaged between 25 and 40 Congressmen and about five Senators a night.” Congressional attendance was noteworthy, but so too was the overall turnout. Despite the Armory's official seating capacity of 5,310, more than 13,000 people packed the venue on opening night, with crowds exceeding 7,000 allowed on subsequent evenings. Even with such limitations, the total attendance for the Washington crusade ultimately reached a half million. As Vice President Alben Barkley marveled to Graham, “You're certainly rockin' the old Capitol.”

33

Interest proved to be so high that Graham soon staged a huge rally at the Capitol itself. At first, the idea seemed impossible. But a call to his patron Sid Richardsonâwho, in turn, called Speaker of the House Sam Rayburnâprompted Congress to push through a special measure authorizing the first religious service ever to be held on the steps of the Capitol Building. “This country needs a revival,” Rayburn explained, “and I believe Billy Graham is bringing it to us.” Even though it took place in a cold drizzling rain, the February service drew a crowd estimated to be as large as forty-five thousand. (The gathering, the House sergeant at arms noted, was larger than the one for Truman's inauguration.) Graham reveled in the

turnout, taking off his tan coat to address them in a powder-blue double-breasted suit with a polka-dot tie. To those assembled, and to the millions more listening over the ABC radio network, he called for Congress to set aside a national day of prayer as a “day of confession of sin, humiliation, repentance, and turning to God at this hour.” The minister noted that a formal return to God would benefit not just the American people but also the political representatives who had the faith to make such a cause their own. “If I would run for President of the United States today on a platform of calling people back to God, back to Christ, back to the Bible, I'd be elected,” Graham insisted. “There is a hunger for God today.”

34

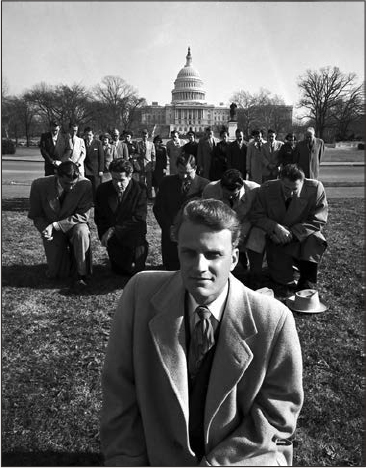

In January 1952, Reverend Billy Graham launched the Washington crusade, staging religious revivals at the National Armory and, in a first for the city, on the steps of the Capitol Building itself. If Congress and the White House “would take the lead in a spiritual and moral awakening,” he said, “it would affect the country more than anything in a long time.”

Mark Kauffman, The LIFE Premium Collection, Getty Images.

The proposal for a national day of prayer was nothing new; several presidents, including Abraham Lincoln, had called for similar religious observances in the past. Graham himself had tried to convince Truman of the need for a national day of prayer during their July 1950 meeting.

The idea generated considerable interest at the time, as ministers across the nation picked up Graham's proposal and urged Americans, in sermons delivered in their own churches and over the radio, to lobby the president. Thousands did. “The minds of the people must be directed more toward spiritual values,” a Cincinnati woman wrote. “The time is

NOW

for

spiritual mobilization

.”

35

Despite the outpouring of public pressure, Truman had not been swayed. The second time around, however, the president gave in. He still had reservations about public displays of prayerâin his diary that month, he noted that he abided by “the V, VI, & VIIth chapters of the Gospel according to St. Matthew,” which were often cited for their injunctions against the practiceâbut he read the national mood and decided to acquiesce.

36

As Congress took up the proposal in February 1952, House majority leader John McCormack let it be known that Truman now supported the plan.

37

Congress resolved, by the unanimous consent of both House and Senate, “that the President shall set aside and proclaim a day each year, other than a Sunday, as a National Day of Prayer, on which the people of the United States may turn to God in prayer and meditation.” The language of the legislation was significant, as all previous congressional proclamations for days of prayer “requested” that the president designate a day, while this one alone “required” him to do so. Truman was thus bound by the law, just as every one of his successors in the White House has been to this day. In an apparent nod to the previous year's “Freedom Under God” observance, which was set to be repeated in 1952, Truman selected the Fourth of July as the date for the first National Day of Prayer. The choice, he explained, was intended to coincide “with the anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, which published to the world this Nation's âfirm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence.'” In the official proclamation, Truman encouraged all Americans to ask God for strength and wisdom and to offer thanks in return “for His constant watchfulness over us in every hour of national prosperity and national peril.” For his own part, the president observed the day of prayer by taking in a doubleheader between the Washington Senators and the New York Yankees. His critics noted with satisfaction that the Yankees beat the home team in both games and that Truman had to leave early when the second was called on account of rain.

38

While Billy Graham welcomed the adoption of the National Day of Prayer, he saw it as merely the beginning of the political and moral transformation needed to save the nation. In late 1951, he insisted that “the Christian people of America will not sit idly by during the 1952 presidential campaign. [They] are going to vote as a bloc for the man with the strongest moral and spiritual platform, regardless of his views on other matters.” By that time, Graham believed he had already found the man who fit the description: General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

39

E

ISENHOWER SEEMED AN UNLIKELY CANDIDATE

to lead the nation to spiritual reawakening. For decades he had remained distant from religion and could not even claim a specific denominational affiliation. During his childhood, however, his family had been deeply devout. His grandfather had been a minister for the River Brethren, an offshoot of the Mennonites, and his father maintained that faith. His mother traveled a more circuitous spiritual path: born and raised a Lutheran, she joined the River Brethren at marriage but was later baptized as a Jehovah's Witness when Dwight was eight years old. While denominations may have varied, the family's commitment to a literal reading of the Bible remained constant, and a constant presence in their lives. In their white clapboard home in Abilene, Kansas, the Bible was a source of inspiration read each morning in prayers and a source of authority to be quoted again and again. “All the Eisenhowers,” one of Dwight's brothers later explained, “are fundamentalists.”

40

Dwight Eisenhower certainly bore the imprint of this upbringingâhe had been named after Dwight Moody, a popular nineteenth-century evangelist who was, in essence, a forerunner of Billy Grahamâbut for much of his adult life he showed little of it publicly. The River Brethren required strict observance of the Sabbath, but Eisenhower rarely attended services during his military career. The Brethren demanded abstinence from tobacco, but he became a heavy smoker, going through four packs of Camels a day during the climax of the Second World War. The Brethren were also strongly committed to pacifism on religious grounds; Eisenhower's mother condemned war as “the devil's business” and believed those waging it were sinners. While most members of the River Brethren

and the Witnesses sought to secure a conscientious-objector exemption from military service during times of war, Eisenhower actively pursued a military career during a time of peace, leaving home in 1911 to enroll at West Point and then rising through the ranks over the course of two global conflicts.

41

In spite of his outward indifference to the faith of his family, Eisenhower insisted that its lessons still resonated with him. “While my brothers and I have always been a little bit ânon-conformist' in the business of actual membership of a particular sect or denomination,” he wrote a friend in 1952, “we are all very earnestly and very seriously religious. We could not help being so considering our upbringing.” Indeed, while he lacked ties to any specific denomination, Eisenhower remained firmly committed to the Bible itself. Like his parents, he considered it an unparalleled resource. One of his aides during the Second World War remembered that Eisenhower could “quote Scripture by the yard,” using it to punctuate points made at staff meetings. After the war, his sense of religion's importance only grew stronger. In an interview before he assumed the presidency of Columbia University in 1948, Eisenhower declared himself “the most intensely religious man I know.” Faith, he believed, was important not just for him personally but also for the entire country. “A democracy cannot exist without a religious base,” he told reporters. “I believe in democracy.”

42