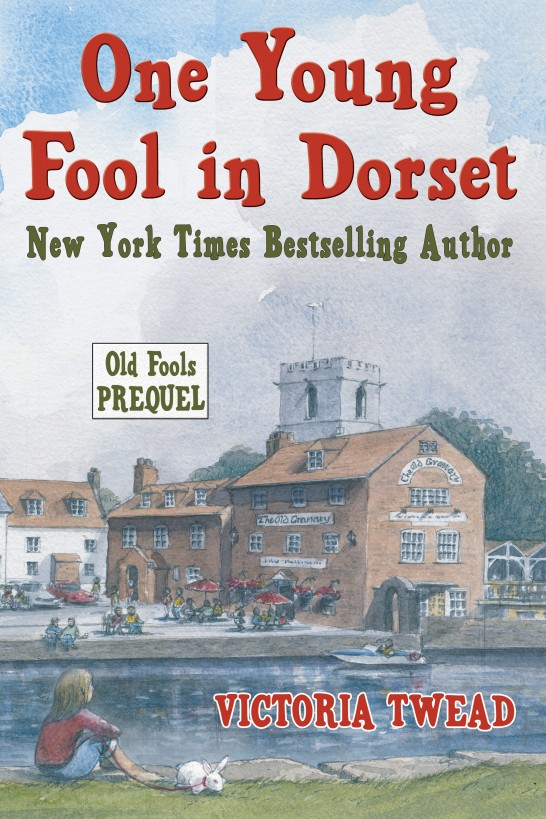

One Young Fool in Dorset

Read One Young Fool in Dorset Online

Authors: Victoria Twead

Tags: #childhood, #memoir, #1960s, #1970s, #family relationships, #dorset, #old fools

IN

DORSET

New York Times and Wall Street Journal Bestselling

Author

One Young Fool in Dorset

is the prequel to the

‘Old Fools’ series.

Also available in Paperback and Large Print

editions.

In loving memory of Jean and Frank.

And with heartfelt thanks to Annabel

who shared her parents with me so unselfishly.

Preview of Chickens, Mules and Two Old

Fools

Childhood and Dorset Recipe Index

Perhaps I’m two years old, maybe less. There is a

garden, and two big strong legs. The legs belong to Lena, our

German nanny. A wicker laundry basket sits beside me. I’m not

interested in the legs. Neither do I care about the wicker basket.

I’m far too busy marvelling at the perfectly spherical little balls

I’m finding in the grass. I amuse myself by collecting a pile. I

pick them up and drop them. They roll down the bank. I taste one.

It isn’t nice.

“She’s playing with rabbit droppings,” pipes a voice

above me. My big sister. “And now she’s eating them.”

Lena swipes the little balls from my chubby grasp. I

howl, but not for long. There is always something else to

explore.

* * *

Now I’m four and play in the front more than the

back, sharing toys with neighbouring kids. We live in a leafy

cul-de-sac lined with white houses, each identical to its

neighbour. There are tall pine trees where red squirrels twitch and

dance. Our quiet street opens onto a bigger, much busier road,

noisy with traffic. Sometimes a big black limousine, with a Union

Jack flag fixed to the bonnet, passes by. White motorcycles, ridden

by men dressed in white uniforms, surround the limousine.

“There’s somebody important in that black car,” says

my big sister.

My sister is four years older than me and already

knows stuff. She is clever and her hair is straight and shiny. Mine

is unruly and points in all directions.

“

Wer?

” I ask in German. “Who?”

“I don’t know, but those men on motorcycles are

called the White Rats.”

I watch, fascinated, until the convoy passes.

It is Germany in the late 1950s and we are stationed

in Bonn because my father is an officer in the Army.

“We’re going to help at the cocktail party tonight,”

says my sister, when the convoy has passed. “We’ll wear our party

dresses and carry trays. Lena says you can help, too.”

I like that idea. My sister has been helping at

cocktail parties for ages, but I’m always told I’m too young. This

will be my first cocktail party. I like my party dress. It is

swishy and white with puffed sleeves, a blue sash and a stiff lacy

petticoat.

Cocktail parties at our house happen often. I sense

that my parents dislike them but they are necessary because of the

Army. Days beforehand, Lena polishes the silver and sweeps the

carpets until everything is spotless. My mother is distracted and

edgy. It all has to be perfect. My father looks handsome,

resplendent in his dress uniform, his moustache bristling.

Upstairs, Lena sponges us down and wipes our faces

and hands.

“Just a lick and a promise today,” she says in

German, “there’s so much to do. Now, go and make a start on getting

dressed. Thank goodness your baby brother is asleep.”

Our clothes are laid out on our beds. My sister and

I dress ourselves as far as we can, petticoat first, then dresses.

I can’t manage the buckles on my party shoes or the many buttons

down the back of my party dress. I toddle off to find Lena.

“You’ve done well,” she says, adjusting my white

socks so that they are the right way round, buckling my shoes and

buttoning the dress. “Now you can go downstairs and hand out

nibbles when the guests arrive. Just for half an hour, mind. Now,

out of my way, and don’t mess up your dress.”

I don’t follow her all the way down. I sit on the

stairs and watch the final preparations through the bannisters. How

pretty Mummy looks with lipstick! How the sherry decanters sparkle

on the sideboard!

The doorbell rings, and Lena hurries away to open

the door to the guests.

Gradually, the room fills up with ladies who screech

with laughter and wear jewellery that flashes signals when the

light catches it. Their husbands stand tall in their uniforms, deep

in conversation with each other. My sister carries a tray and

weaves in and out through the knots of people, pausing to offer

dainty nibbles. My mother wears a painted-on lipstick smile. At

first, I can hear her making conversation using her brittle

telephone voice, then, as the room fills and the noise level rises

to a continuous buzz, I can no longer make out individual

voices.

“Victoria! There you are!” Lena grabs my arm and

helps me down the stairs and into the throng. “Don’t be shy! Take

this bowl and offer it to the guests. Just like your sister is

doing.”

I like the way my party dress rustles and swishes. I

walk though the haze of perfume and forest of legs, then stop and

hold my bowl up. Perhaps my sister has already done her job too

well, because nobody takes any. I move on. Even when I tap on legs,

the guests barely notice me.

I set the bowl carefully back on the sideboard. Now

I just meander between the clusters of people, listening to the

buzz, the sudden brays of laughter, hypnotised by the rustle of my

own skirts. I lift my party dress to see the lacy petticoat

beneath. Then I lift that, too.

“Lena! Victoria has no knickers on! And she’s

showing

everybody!

”

Strong German arms whisk me away and I am put to

bed. The party is over for me and Lena resolves to supervise my

dressing more closely in future.

* * *

I was born in 1955, in Dorchester in the UK, the

nearest hospital to Bovington Army Camp where my father was

stationed. The hospital, built in 1841 from local Portland stone,

has now been converted to flats, but still looks much the same as

it always did. I only just managed to be born on British soil

because six months later our family was sent to Bonn. My sister was

already four years old and my brother was destined to be born two

years later. I was the peanut butter in the middle of the

sandwich.

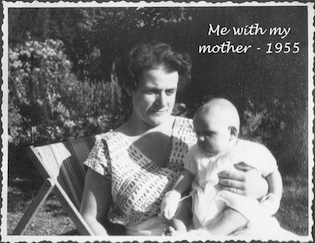

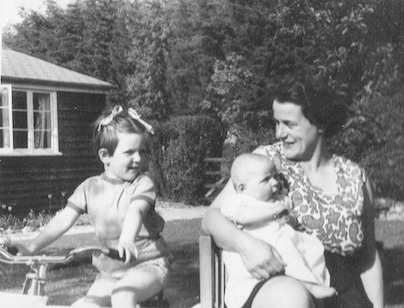

My mother, big

My mother, big

sister and me at Bovington

Only ghosts of memories stay with me when I think of

those first five years in Germany. Being Austrian, my mother’s

first language was German, although she was fluent in English, too.

Lena, our nanny, spoke only German. My father, although English,

spoke good German. I grew up knowing only German, but my sister,

who was now at the army school, was already bilingual.

I remember there were monkeys at the petrol station.

I always begged Lena to walk that way so that we could see the

monkeys in the cage. As we passed, the monkeys leapt from one side

to the other, making the cage rattle alarmingly.

I remember walking beside Lena as she pushed my

newborn brother in a huge pram alongside the river Rhine. The water

was brown and the river was so big I could hardly see the other

side. Dirty waves lapped at the bank. I licked at my ice cream

until, horror, the cone crumbled in my hand and the ice cream

splatted on the cement path. I opened my mouth to howl, but stopped

when a dachshund popped up from nowhere and lapped the path clean

with a few deft licks from his pink tongue.

I recall taking a ferry across the Rhine to go to

kindergarten. At Christmas, I remember a wonderful cardboard

structure on a table in the classroom. It was like a church but

with turrets, battlements and windows with arched shutters. Each

little window was numbered and we children took it in turns to open

a set of cardboard shutters every day to reveal a stained-glass

window made from coloured tissue paper. Candles had been lit inside

the structure. It was the first Advent calendar I had ever seen,

and still remains the most beautiful. I suspect it must have been a

huge fire hazard and would certainly have never passed today’s

stringent health and safety rules.

Later, I think I was also sent for a short time to

an army-organised preschool group, where only English was spoken. I

understood very little that the teacher said. I wasn’t happy

because one of the rules was that you had to ask permission to

leave the room if you were going to sneeze. I was terrified that a

sneeze might sneak up on me, unannounced, before I had time to ask

permission to leave the room. And what was the point of saying

‘Present’ when my name was called in the morning? That present

never materialised.

Our car was a black Rover 90 and my sister said it

belonged to the Queen. Apparently we were just borrowing it.

Most of my memories of Germany are mere snatches.

Like the terrifying person called

Schwarz Peter

(Black

Peter) who carried a small whip and followed St. Nicholas (Father

Christmas) looking for bad children to punish; eating yoghurt from

glass jars with long spoons; the children’s book

Der

Struwwelpeter

(Shockheaded Peter) which showed a boy who never

cut his hair or nails, a cautionary tale to scare young children;

and staring curiously at the floppy thing the boy next door kept in

his underpants and insisted on showing me whenever he had the

opportunity.

When I was five, the family returned to Dorset,

England, leaving Lena behind. But my parents refused to stay in

Army quarters this time, and the search began for ‘the perfect

house’.