Oswald and the CIA: The Documented Truth About the Unknown Relationship Between the U.S. Government and the Alleged Killer of JFK (46 page)

Authors: John Newman

Hosty Checks the "Postmaster"

The vagaries in the FBI's story of how and when it learned of Oswald's move to Magazine Street beckon us to look again at this central subject. Is it possible that after three months Dallas had still not learned of Oswald's forwarding address? What is the documentary evidence for the FBI's claim to the Warren Commission that it did not know about Oswald's move to New Orleans until two months after his arrival there? There are just two FBI documentsboth from Dallas-that buttress this proposition. One was a July 29, 1963, Dallas office memo stating that Oswald had left Neely Street without leaving a forwarding address.14 This was based on an earlier, May 28, internal memo from Special Agent Hosty to SAC Shanklin." Thus, the evidence boils down to one sentence in a memo written by Hosty: He said a "check with the Postmaster" showed that Oswald had moved without leaving a forwarding address.

As discussed in Chapter Fifteen, the Dallas FBI office had closed the Oswald case in October 1962 and reopened it in March 1963. A file on Marina had been opened in the interim, but no attempt to interview her had been made until March 11, 1963, when Hosty had learned from the apartment manager for Oswald's 602 Elsbeth apartment, Mrs. M. F. Tobias, that the Oswald family had moved on March 3. What did Hosty do to find out where Oswald had gone? He had a dependable source: the U.S. post office. Hosty wasted no time, and contacted an FBI informant there, Mrs. Dorthea Myers. She told Hosty that the Oswalds had moved into 214 West Neely in Dallas. 16 That was the address at which Oswald remained until he moved to New Orleans on April 24. The question is: When did Hosty find out Oswald was no longer on Neely Street?

On May 27, 1963, someone from the Dallas office of the FBI (probably Hosty) attempted to interview Oswald and Marina "under pretext." A pretext interview is a subterfuge in which the true purpose and often the true identity of the interviewer are disguised. The FBI person doing the checking discovered the Oswalds were gone, and the next day, May 28, Hosty wrote this memo to Shanklin, the special agent in charge in Dallas:

On 5/27/63 an attempt to interview subjects at 214 Neely, Dallas under pretext reflected that they had moved from their residence. A check with the Postmaster reflects that the subjects have moved and left no forwarding address.

The owner of subjects['] former residence at 214 Neely Dallas, M.W. George TA 3 9729 and LA6 7268 will be interviewed for information re subjects as will subject[' ]s Brother in Fort Worth."

This memo deserves our close attention. FBI director Clarence Kelly's account-much of it perhaps written by Hosty-claims that Hosty actually discovered the Oswalds had vacated the Neely Street apartment twelve days earlier, on May 15.18 Researchers have been unable to see this contradiction because the first paragraph of the above Hosty memo remained classified until 1994.

The release of the full memo in 1994 exposes more than the conflict between dates (May 15 and 27) for the attempted pretext interview at Neely Street. The unredacted version of this memo points to some glaring deficiencies in Hosty's account to Shanklin and the FBI's account to the Warren Commission. The second sentence contains three claims: I) Hosty or a colleague checked with "the Postmaster," 2) this check showed that the Oswalds had moved, and 3) this check showed that the Oswalds "left no forwarding address." It was strange that Hosty, normally so precise in the "who what when where, and how" department, neglected to give the name of the "Postmaster." The standard operating procedure for these internal memos was to name the informant and specify "(protect identity)" if the name was considered sensitive. For external memos an informant number was always used (such as "T-1" or "NO-6") and the names supplied in a detachable administrative cover sheet. The second point, that the "Postmaster" check showed the Oswalds had moved, is suspicious because it is logically incongruous with the third point, namely, that they had left no forwarding address. If the Oswalds had not provided a forwarding address, how did this "Postmaster" know that they had moved? Would Oswald have contacted the "Postmaster" just to say "we're moving"?

The third point-that Oswald had left no forwarding address-is the most startling error. Oswald did leave a forwarding address. Tucked away in the twenty-six volumes of Warren Commission materials is Commission Exhibit 793, which is a change-of-address card that Oswald sent to the Dallas post office after his arrival in New Orleans." Oswald listed May 12 as the effective date, which is probably the date he mailed it. The card is stamped "May 14, 1963," indicating this was the date when the post office received it, which is either one day or thirteen days before Hosty checked with the "Postmaster," depending on which version of his story we are dealing with. The FBI's top handwriting expert, James C. Cadigan, who had more than twenty-three years of experience, testified that the handwriting was Oswald's.20 Cadigan's handiwork-a marked-up copy of the card-can be found in another location of the Warren Commission's published materials.21

Within hours of the Kennedy assassination, the Dallas office of the FBI sent an "urgent" cable to Bureau headquarters and the New Orleans FBI office. That cable included this information:

Inspector Harry Holmes, US Post Office, Dallas, advised tonight [a] check of postal records at Dallas rep(f)lects following info.

On May ten last [10 May 1963], USPO, main branch, Dallas, received forwarding order for any mail for Mrs. Lee H. Oswald to be forwarded from box two nine one five, located main PO, Dallas, to two five one five West Fifth St., Irving, Texas. On May fourteen last [14 May 1963], PO received forwarding order again for mail in box two nine one five, Dallas, for Mr. Lee H. Oswald to be forwarded to four nine zero seven Magazine, New Orleans, La. Post Office subsequently had forwarding order from Mrs. Lee H. Oswald, date unknown, to forward all mail for Mrs. Lee H. Oswald to box three zero zero six one New Orleans.22

Hosty's claim to have queried the "Postmaster" was dubious. Hosty's claim that such a check showed the Oswalds had moved without leaving a forwarding address is baseless. Hosty's claims provide the only documentary evidence buttressing the FBI's story that it did not learn of Oswald's move to New Orleans until June 26. This story is headed for a new conclusion.

More Than the Postmaster Knew

The idea that the FBI did not know where Oswald lived from April 24 until June 26 is incredulous, especially so in view of all the sources to whom Oswald had immediately mailed his Magazine Street address. This is the key point: For thirty years the first paragraph of Hosty's May 28 memo to Shanklin has been classified. Underneath that redaction has been the solitary sentence that is the documentary basis for the FBI's response to the Warren Commission on when and how the FBI learned of Oswald's move to New Orleans. The withholding of this evidence, which turned out to be false, did significant damage to the public's ability to understand the facts.

The list of problems that surround Hosty's suspicious May 28 story about a "check with the Postmaster" underlines the need to examine the facts to which the FBI had access indicating that on May 10, 1963, Oswald had moved into an apartment at 4907 Magazine Street.23 From the documents available, there were at least seven occasions when the FBI might have learned about Oswald's Magazine Street address prior to June 26-the date it claimed it learned of Oswald's post office box in New Orleans. Four of these opportunities occurred before Hosty's May 28 note to Shanklin, and all were well before June 26.

The first communication containing Oswald's Magazine Street address was the change-of-address card he sent on May 9, 1963, effective May 12, and received at the Dallas post office on May 14.24 Presumably the Irving change-of-address card that Marina sent to the Dallas post office on May 10 would have been available with Oswald's card. The second opportune communication with the Magazine Street address was the notice Oswald mailed to the Dallas post office on May 12, 1963, asking them to close his old box, 2915.25 Given the close cooperation between the Dallas post office and the FBI on Oswald's mail activities, the Bureau should have learned about this address card and the box closure soon after these events occurred.

The third communication that should have tipped off the FBI happened on May 14, 1963, when Oswald sent a change-of-address card-with the new 4907 Magazine Street address-to the FPCC.26 Given that the FBI gained access to Oswald's letters to the FPCC through an informant for the New York FBI office, the Bureau should have learned about this letter sometime in May. Skipping out of order, the fifth and sixth communications occurred on May 22, when FPCC national director V. T. Lee wrote to Oswald at 4907 Magazine," and on May 29, when the FPCC sent Oswald a membership card28 and told him it was all right to form a New Orleans chapter.29 Because access to FPCC offices probably required a breakin, we cannot be sure the FBI had access to these three letters.

The fourth and seventh events that should have enabled the FBI to learn of Oswald's whereabouts are more intriguing. They were the May 17 change-of-address card Oswald sent to the Soviet Embassy in Washington, D.C., alerting them to his new Magazine Street address,30 and a June 4 letter to Marina-mailed to 4907 Magazine Street-from the embassy, asking her why she wished to return to the Soviet Union." The early 1960s were tense years in the U.S.- Soviet Cold War, and the Soviet Embassy in Washington was enemy territory as far as the FBI and CIA were concerned. That embassy would have been among the highest priority targets of the American intelligence community, and the embassy's mail would have been carefully watched-especially mail to and from Soviet citizens in America.

We know from FBI files that "the highly confidential mail coverage of the Embassy" was handled by agents from the FBI's Washington field office.32 The day after the Kennedy assassination, FBI director Hoover, in a telephone conversation with President Johnson, explained:

Now, of course, that letter information, we process all mail that goes to the Soviet Embassy-it's a very secret operation. No mail is delivered to the Embassy without being examined and opened by us, so that we know what they receive.33

Based on this statement, it is reasonable to believe that at least the May 17 Oswald change-of-address card and the June 4 embassy letter to Marina were known to the FBI.

We can now return to the FBI's incredible claim that it did not know about Oswald's move to New Orleans until June 26, and recall that it was on this date that a New York informant mentioned seeing P.O. Box 30061 on Oswald's June 10 letter from New Orleans to the Worker.34 Since New York was being credited as the source for this story, the purpose of feigning ignorance of any of the above seven events could not have been to hide the Bureau's sources in New York-as sensitive and valuable as those sources were. No, the purpose would more likely have been to cover something even more sensitive. Perhaps it was to cover the FBI's interception of the letter to the Soviet Embassy, or perhaps even to cover the CIA's interception, on May 22, of the Titovitz letter to Marina by its super-secret HT/LINGUAL program (this letter opening was discussed in Chapter Fifteen). On the other hand, there does not appear to have been enough time for Marina to have notified Titovitz of the Magazine Street address and receive his reply between May 10 and 22.

The FBI's operation to open the Soviet Embassy's mail might have required a false cover story to hide it, but this would still not explain why Hosty would not have learned from any of Oswald's three communications to the Dallas post office about his relocation to Magazine Street in New Orleans. Furthermore, Special Agent Hosty's May 28 memo said that Oswald's brother and the owner of Oswald's old West Neely address would be "interviewed for information re subjects [Oswald and Marina]." There is no indication that Hosty followed up anytime soon. If Hosty really wanted to find out, all he had to do was go to the post office, just as he had done when he had learned of Oswald's previous move, from Elsbeth to Neely Street.

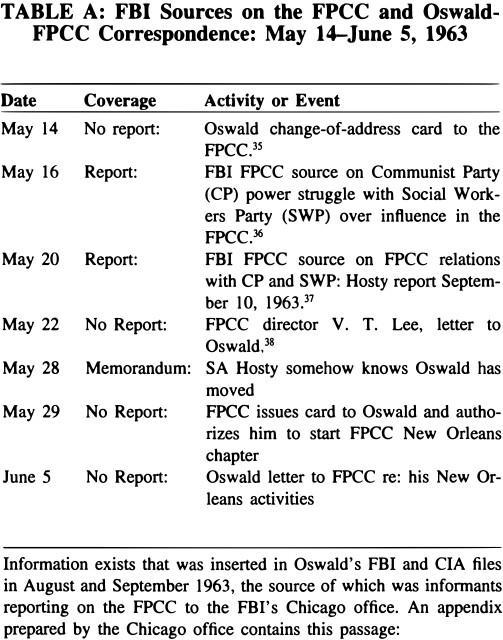

It is possible but unlikely that the FBI did not intercept mail between Oswald and the FPCC on May 14, 22, and 29, and June 5. We do know that the FBI had access to Oswald's mail to the FPCC. In addition, we also know that the FBI had productive sources in the FPCC.

On May 16, 1963, a source advised that during the first two years of the FPCC's existence there was a struggle between Communist Party (CP) and Socialist Workers Party (SWP) elements to exert their power within the FPCC and thereby influence FPCC policy. However, during the past year this source observed there has been a successful effort by FPCC leadership to minimize the role of these and other organizations in the FPCC so that today their influence is negligible.

On May 20, 1963, a second source advised that the National Headquarters of the FPCC is located in Room 329 at 799 Broadway, New York City. According to this source, the position of National Office Director was created in the Fall of 1962 and was filled by Vincent "Ted" Lee, who now formulates FPCC policy. This source, observed Lee, has followed a course of entertaining and accepting the cooperation of many other organizations including the CP and SWP when he has felt it would be to his personal benefit as well as the FPCC's. However, Lee has indicated to this source he has no intention of permitting FPCC policy to be determined by any other organization. Lee feels the FPCC should advocate resumption of diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United States and support the right of Cubans to manage their revolution without interference from other nationals, but not support the Cuban revolution per se.39