Other Women (11 page)

Authors: Fiona McDonald

Mistresses of the

Aristocracy

HE MISTRESSES OF THE DUKE

OF

D

EVONSHIRE

William Cavendish became the 5th Duke of Devonshire when he was age 16. His father had died a rather embittered man, dismissed from his post as Lord Chamberlain by George III because of his leadership of the Whig party. The young king subsequently assembled his own government; one he thought he could trust.

William, on becoming Duke of Devonshire, was automatically catapulted into the middle of Whig politics; a position for which he had neither the interest nor the talent. It was remarked by some of his colleagues in the party that, although he looked the part, he did not have the aptitude and was well known for his indifference. The same indifference seems to have spread to the feelings he had for his first wife, Georgiana Spencer. Various sources suggest that he was a man who liked his women particularly attentive to his comfort, who pandered to his whims and who did not make great public waves, as she tended to do.

Whatever the secret to his charm, twice during his lifetime the duke had both a wife and mistress – the same wife but a different mistress. The second mistress was taken into the bosom of his family and became indispensable to both husband and wife in a genuine ménage a trois.

The three women presented here have stories that intertwine so it seems best to tell their stories together: Georgiana Cavendish, the Duchess of Devonshire (b.1757; d.1806); Charlotte Spencer (d.1778); Lady Elizabeth Hervey Foster (later Duchess of Devonshire) (b.1759; d.1824).

Georgiana was a beautiful, intelligent young woman who earned a reputation for being both a leader of fashion and a notorious gambler. Her life with her husband and his mistresses is a fascinating one.

Georgiana’s father was John Spencer, 1st Earl Spencer; her mother was Lady Margaret Spencer (

née

Poyntz). Georgiana, the eldest child of three, was her mother’s favourite and the two declared themselves best friends. Poor little Harriet who came along five years later was not so lucky, her mother pronounced her as an ugly baby and left it at that.

When she was 16 Georgiana was introduced to the 24-year-old Duke of Devonshire. After a brief interlude, in which the two young people were thrown together socially, the duke put forward his request to marry Georgiana. The offer was accepted and the date of the wedding set for Georgiana’s seventeenth birthday. The match was considered a very good one. The Spencers and the Devonshires were socially on a par and Georgiana was going to have a splendid dowry settled on her at marriage; the duke was good-looking and charming.

Georgiana’s wedding was an expensive affair. Her family spent a lot of money setting her up with wedding clothes and jewels, post-wedding clothes such as walking dresses, ball gowns, morning dresses, riding habits, stockings, gloves, hats, shoes (reportedly sixty-five pairs) and anything else that would help make her happy in her new home and enhance her beauty as a showpiece for her husband. Even though a lot of time and money went into the preparations, only five people actually attended the wedding itself.

What more could a 17-year-old girl want? One thing she certainly did not want was a rival for her new husband’s affections. Charlotte Spencer – and no, she was not related to Georgiana’s family – already had a strong hold on the duke’s heart.

Charlotte had been destined to become a milliner in London. Her father was a clergyman with a poor living who died when she was a teenager. Although she could have made a go of it in the city, her life took an abrupt turn for the worse almost as soon as she stepped off the coach. A common practice in those days was for parasitic men to introduce themselves to young country girls as they alighted in London. They offered to help them find accommodation and work or offered them love and marriage; the results were usually disastrous. Seduced and abandoned Charlotte found refuge with a wealthy old man who took her in and looked after her. On his death, which was not long after they began living together, Charlotte found he had provided for her in his will, leaving her enough money to become the owner of a hat shop, not just an employee in one. Charlotte was back on track with her career – until the Duke of Devonshire happened to pass by her little boutique and fall in love with her.

There were perhaps worse things that could have happened to her. The duke established Charlotte in a comfortable house with servants to wait on her, and he would come and make love to her. She may have even kept the management of her hat shop.

One woman’s happiness often seems to be linked to another’s despair. Charlotte had a baby girl, also named Charlotte, not long before the unsuspecting Lady Georgiana married William, the 5th Duke of Devonshire. It was no wonder that Georgiana found his embraces rather cold, as his heart was elsewhere.

Charlotte Spencer, the thorn in the new bride’s side, only lived another four years, but these may have been four too many for Georgiana who, although she never mentioned any names, must have been aware of the mistress’s existence. Georgiana herself was having trouble conceiving or carrying a child to full term. It would be nine years before she successfully gave birth. Therefore it must have been painful to know that her husband was enjoying fatherhood at another woman’s house.

When Charlotte Spencer died, Georgiana had no objections whatsoever to the arrival at her house of her husband’s illegitimate daughter. Little Charlotte became Georgiana’s sweetheart, the child she could not have herself. They decided to give the child her father’s Christian name, William, as a surname, altering it only slightly by adding an ‘s’ to the end. This was common practice at the time, giving a father’s name as a surname, keeping the blood ties linked while not acknowledging the relationship any more than could be avoided. In the case of Charlotte Williams, her story was that she was the orphan child of a distant relation of Georgiana’s.

Georgiana Cavendish

By the time Charlotte Williams had made her debut into the household of her father and so-called distant cousin, Georgiana had found another absorbing but expensive hobby. She had become a ruthless and compulsive gambler. She was the darling of society with her beauty and fashion, her wit and general affability. Her open friendliness and compassion for those less fortunate than herself earned Georgiana many friends in the lower classes as well as with her peers.

Probably in a bid to stem some of her hurt and loneliness, Georgiana had taken to the gaming tables, as much for social contact and to be admired and loved as for any other reason, but she was soon hooked on trying to win money. Unfortunately she lost more than she won, often exceeding her already generous allowance of £4,000 a year. The first time she found herself in real debt she applied to her parents for help. Her mother, always ready to stand by her eldest daughter, agreed to pay off the sum but only on the condition that Georgiana tell her husband about it. The duke’s reaction to his wife’s profligacy was extremely surprising. He paid her parents back in full and walked away, never mentioning the subject again; there was no admonishment, no outrage. Georgiana must have felt as though she was invisible to such a cool husband.

One of the greatest influences on the young duchess’s life was meeting the politician Charles James Fox. He was 28 when they met in 1777 and not at all good-looking. His short, stout figure was not particularly suitable for the extravagant fashions he chose to wear, but he, like Georgiana, enjoyed attracting attention with his bizarre styles; changing his hair colour from one day to the next was one of his favourite pastimes. Charles was also a gambler and had run up debts that made Georgiana’s look petty.

Apart from being lively and entertaining Charles Fox gave Georgiana intellectual stimulation and a strong, supportive friendship. It was Charles who first got the duchess interested in politics. She became a devout campaigner for his party.

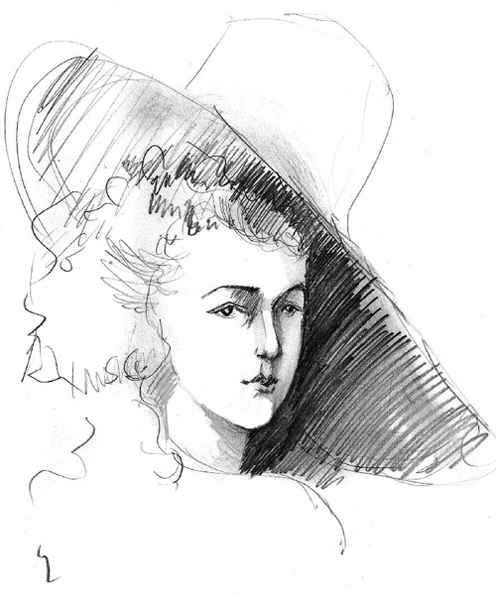

Elizabeth Hervey Foster

With motivation coming from several of her friends, including Fox, Georgiana wrote a novel,

The Sylph

, which was published anonymously in 1779 although it was attributed to ‘a young lady’. The contents were often autobiographical and dealt with a loveless marriage like her own.

During a visit to Bath, for health reasons, Georgiana made friends with a young woman of social standing, Lady Elizabeth Foster,

née

Hervey. Elizabeth was the daughter of a clergyman, not a poor one as Charlotte’s father had been but one who lived well beyond his means. As a younger son he had entered the Church, as was common for those being the third in line for inheritance, thinking it unlikely that he ever would inherit. At some point he was appointed the Bishop of Derry, although this did little to relieve the constant financial difficulties the family found itself in. It was as the daughter of the Bishop of Derry that Elizabeth in 1776 was married off to Irishman John Thomas Foster, a respectable man who did not feel the need for a dowry (the bishop, as a spendthrift, had nothing to offer the man who took his daughter off his hands). Mr Foster seemed to be a rather serious young man who was the opposite of his father-in-law, in money matters at least.

At the time of Elizabeth’s marriage it was deemed a very good match for a penniless young woman, even if she did come from aristocratic stock. Three years after her marriage, the unexpected happened and her father inherited the title of 4th Earl of Bristol on the death of his second eldest brother who, like the eldest brother before him, had been without legitimate children. Plain Elizabeth Foster became Lady Elizabeth.

Although Elizabeth complained bitterly to her new best friend Georgiana that she had never wanted to marry John Foster, and had begged her parents not to make her accept, a different point of view had been put forward by her parents. They claimed that it was entirely a love match between the two young people and that they were only too happy to approve their daughter’s choice.

If the marriage of Elizabeth Christiana Hervey to John Foster was originally a love match, by 1780 it most definitely was not. Elizabeth was pregnant with the couple’s second child. Foster was accused of seducing his wife’s maid and this was the story that Elizabeth’s family supported when their daughter’s marriage failed. Foster refused to try to reconcile and insisted on a permanent separation. Under the rules of the separation Foster enforced his right to have custody of the two children. Elizabeth was not allowed to see her two boys for fourteen years. Foster also refused to maintain his wife after their break-up. Elizabeth Foster was returned to her parents to be supported by them.

The Earl of Bristol gave his daughter an allowance of £300 a year. It was an amount that was considered well below that needed to maintain the standard of an earl’s daughter. Even in this the earl was so careless with money that the allowance was not paid regularly and Elizabeth was often short of money, even for necessities.

It was as the penniless and abandoned wife of a man who had used her cruelly that Elizabeth came to be friends with Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. Perhaps the two young women felt an affinity through the lack of love from their spouses. The result was that during the Devonshires’ time in Bath, Georgiana took it on herself to take Elizabeth Foster under her protective wing.