Other Women (15 page)

Authors: Fiona McDonald

The marriage made the pair respectable at last. They could, if they wanted to, appear at parties together, but they chose not to. They lived a very quiet life together, talking and writing, the kind of life Harriet had dreamed of. Her children certainly did not resent the marriage and became the couple’s only family, as all their other relatives had washed their hands of them.

In 1858 Harriet died. Mill lived on for at least a decade after her death, still writing and dedicating works to her. He did not marry again. Helen Taylor, Harriett’s daughter by her first husband, had always been a supporter of her mother and Mill and helped him with his work on women’s rights for fifteen years after her mother’s death, in fact until Mill’s death in 1873.

And what happened to Lizzie Flower and William Johnson Fox? They continued to live together until their deaths, which both occurred in 1846. It has been long said that the relationship was chaste, but this seems unlikely.

HE

R

OMANTIC POETS AND

A TALE OF TWO SISTERS

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley and Claire Clairmont were brought together when Mary’s widowed father married Claire’s mother who lived next door. The two girls were about the same age and both very young when their respective parents got together. What bound them together over the years was their mutual affection for the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. The friendship between the women waxed and waned. Claire was jealous of Mary’s and Shelley’s relationship, Mary was jealous of Claire spending time alone with Shelley. Claire wanted more attention: she wasn’t as pretty as Mary, she wasn’t as clever, and she was not the daughter of two revolutionary thinkers. The lives of these two sisters are inextricably entwined and to talk about one means including the other. As they were both mistresses of married men they are each suitably qualified to have their stories told here, but for the sake of clarity it will be told as one tale.

Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley is probably most well known as the author of

Frankenstein

, she is probably next well known as the second wife of the Romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. She is also, as the first of her two names suggest, the daughter of the women’s rights advocate, Mary Wollstonecraft. As the daughter of Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, the radical philosopher, Mary was the heiress to some very avant-garde ideas and was brought up in an atmosphere of liberty and independence. Mary’s mother died shortly after her birth, leaving her and another daughter from a previous relationship, Fanny, for Godwin to bring up on his own. Despite Godwin’s ideals about love and marriage, he took a second wife, Mary Jane Vial, or Clairmont as she preferred to be called (it is unlikely that Mary Jane had ever been married to the man whose surname she used, although it may have belonged to one of her lovers). Mary Jane already had two children, a son and a daughter, both of whom were illegitimate. It is doubtful that Mary Jane was the wicked stepmother that Mary Godwin made her out to be; certainly Fanny Imlay, Mary’s half-sister on her mother’s side (and therefore unrelated by blood to either Godwin or Mary Jane) told her sister not to be cruel to their stepmother as she didn’t deserve it. Mary was the favourite child of her father, while his second wife was devoted to her own children. Poor Fanny was the one who was really left out, Godwin was not her natural father and Mary Jane was not her mother; Fanny was the quietest and most conventional of the lot and the one who was left to look after both parents when Mary and Jane had disappeared with Shelley. As children, the three girls and Charles, the eldest of the two Clairmonts, got on very well together. Charles and Fanny (unrelated by blood) were so fond of Mary and Jane that when Godwin banned them from visiting the tainted Shelley household, the two of them would sneak out and do what they could to help their sisters.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

As a child and teenager Mary Godwin was precocious. She already had a published work by the time she was 12. She could travel long distances by herself and was at ease in new and mixed company. Growing up in her father’s house Mary was exposed to many of the philosophers, writers and leading thinkers of the day. She could converse just as happily with men older than her father or not much older than herself.

Jane Vial Clairmont – a name that she later changed to Claire Clairmont and became known by – was the illegitimate daughter of Mary Vial and an unknown man, that is until 2010 when it came to light that her natural father was John Lethbridge of Sandhill Park in Somerset (he was not, however, the father of Jane’s brother). Jane was an attractive girl, dark haired and buxom with a lovely singing voice. It would be unfair to say she was uneducated or dull, she was neither, but it may well be that her stepsister outshone her. Also, poor Jane did not have that one fascinating feature that Mary had: she was not the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin.

The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley had become an acquaintance of William Godwin while Mary was away in Scotland. Shelley and Godwin were busy hatching plans for accessing some of Shelley’s inheritance so that it could be lent to Godwin and relieve him of deep debt. When Godwin’s beautiful, clever, 16-year-old daughter burst onto the scene back in her father’s house in London, Shelley suddenly increased his visits.

Shelley had long been an admirer of Godwin’s work and, as an inexperienced teenager, he liked to let everyone know where he stood on the subject of marriage. To Shelley it was deemed an incarceration; it shackled couples together for a life sentence when all passion, if there ever had been any, had long since died. It is rather extraordinary then, that after having embarked on a steamy correspondence with Harriet Westbrook, a schoolmate of his sister – in response to her cries for help he had taken it upon his teenage self to rescue her – they eloped to Scotland and were married. England at the time would not allow a 16-year-old girl to marry without her parents’ permission.

On their way to the border, the young couple dropped in on Shelley’s friend Thomas Jefferson Hogg to ask for some money. During their month-long honeymoon in Edinburgh, Hogg discovered that against all the odds, Mr and Mrs Shelley seemed as though they might make excellent lifelong companions. Harriet was keen to impress her husband and knuckled down to a serious regime of study. They read, wrote, translated and talked. Shelley was keen for all his women to learn foreign languages: Greek, Latin, French, Italian and German. Harriet was no exception.

Back in England the repercussions of a hasty marriage on no income began to assert itself. Although Shelley would inherit handsomely on his father’s death, until that time he was as dependent on his father’s goodwill as any profligate son. He installed his new bride in lodgings and went off to Sussex to try to get access to some of his inheritance through the intervention of his uncle. During his absence Harriet was left in the care of Thomas Hogg who, as a friend of Shelley’s, also subscribed to his philosophy on free love. With Shelley conveniently out of the way Hogg made a move on Harriet, who was appalled. On Shelley’s return she told him what had happened. Shelley, preferring to take his new bride’s side, wrote to Hogg chastising him for trying to seduce Harriet, telling his friend he thought his actions to be sneaky and underhand.

In order that the couple’s first child, a daughter, Ianthe, should be considered legitimate, Shelley and Harriet underwent a second marriage in case their Scottish vows were not considered legal. For a man who didn’t believe in marriage, marrying once seemed a bit hypocritical, but then to marry the same woman a second time, so that their daughter should be legitimate, seems extra hypocritical. Shelley’s supposed disgust at marriage was for those very social reasons that he was now giving in to: social status and acceptance.

Just prior to his second marriage to Harriet, Shelley had met Mary Godwin. For Shelley it was love at first sight and may well have been for Mary as well. In contrast to the bright young, intellectual attractions of Mary Godwin was the deadening pall of marriage and fatherhood. Shelley was tiring of his young wife and her demands for attention and stability. Shelley saw this as a stifling of his creative faculties and began to resent Harriet and Ianthe. However, the Godwin’s were not very happy with the state of affairs when it became obvious that Mary was falling for Shelley, and vice versa.

The Godwins were liberal thinkers. William and Mary had explored ideas about marriage and what it meant for women’s rights and the freedom of the individual. However, when it became known to Godwin that his favourite offspring was falling in love with a man who was not only married but had one child and another on the way, his thoughts on free love began to waiver. It was one thing to talk about these things and another to witness the realities that accompanied them. While Shelley and Mary Godwin were relishing their new and profound love, Harriet, the abandoned pregnant spouse, was suffering extremely from hurt and fear of being left alone with two children to provide for. Without being too judgemental towards Shelley and Mary Godwin, it is hard not to think that by following one’s own passions at the cost of another’s the rights of that other person are diminished. In short, William Godwin forbade his daughter to continue relations with Shelley, and the young poet was banned from visiting the Godwin household.

Trying to put an embargo on Mary was futile. She, aided by her stepsister Jane Clairmont (later known as Claire Clairmont), connived to see Shelley frequently outside the house. One of their favourite trysting places was the graveyard of the Old St Pancras Church where Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Godwin’s mother, was buried. It is suggested that it was in the shade of her mother’s grave that Mary lost her virginity to Shelley and conceived their first child. Jane was the lookout as well as the supposed chaperone. It has long been speculated as to what young Jane got out of the adventure. It is possible that she was in love with Shelley herself, or that she longed for a similar grand passion. Perhaps she was just bored or lonely. Whichever it was, Jane Clairmont became an almost permanent attachment to Mary and Shelley throughout their lives.

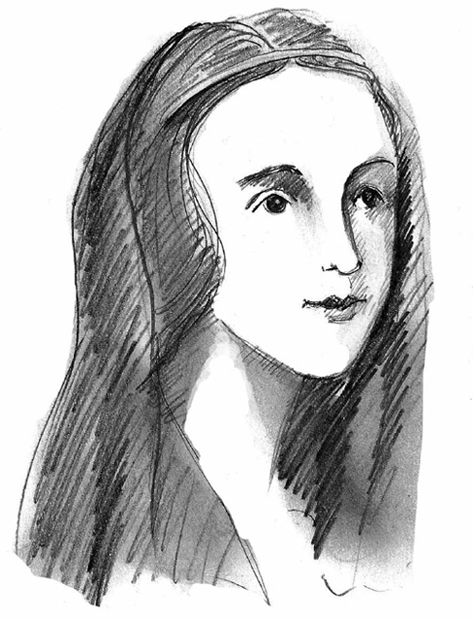

Mary Shelley

In 1814, towards the end of July, the two sisters eloped with Shelley. He had a hackney coach wait at the end of the street at about 5 a.m. Two cloaked figures slipped out of the house in Skinner Street and boarded the vehicle with the waiting Shelley inside. He had left his wife, pregnant with their second child, and had arranged for himself, Mary and Jane to flee to Dover so they could take a boat to Calais, well out of reach of angry fathers or abandoned spouses. When Jane was an old lady she wrote that she had gone with Mary and Shelley only because she was tricked into it and had been very reluctant to continue with the journey when she discovered what they were truly about. This seems highly unlikely and the story would appear to be Jane’s attempts to bring a semblance of respectability to her own youth.

Shelley’s constant problem was lack of money and he certainly had none to spare when he ran away with the Godwin girls. On arriving in Dover he had to break it to them that he couldn’t afford a proper passage for them to travel to Calais and the three of them ended up making the crossing in an open boat. Mary was seasick, which Shelley found touching and revelled in holding her in his arms for the entire journey. It is possible that she was already pregnant by this time and the seasickness was compounded by morning sickness.