Other Women (17 page)

Authors: Fiona McDonald

They set themselves up in the Hotel d’Angleterre and waited Byron’s arrival. Within ten days he too was settled at the hotel. Claire sent a letter to him straightaway telling him that she was there too and available for his pleasure. No reply was made.

Shelley was in heaven. He and Byron, after their introduction, were getting on like a house on fire. They could talk poetry, philosophy and boating. There were days of walking, sailing and talking, endlessly. Byron moved into a villa beside the lake and the Shelleys moved into one not more than ten minutes away. The parties met nearly every day. Claire managed to reignite Byron’s interest, although for him it was purely sexual. He is supposed to have told a friend that with a young girl throwing herself at him what else was he to do?

The weather turned bad, as it was want to do, and the friends were forced to spend long periods of time together indoors. It was one such occasion that led to the famous challenge that everyone should think up a ghost story. Mary, claiming she couldn’t think of one, then had a vision one night that led to the writing of

Frankenstein

. Later, Shelley helped her with its composition. He suggested plot changes and edited the story for her; when they were back in England he also arranged for a publisher to publish it. Byron told Shelley how much he admired Mary; Claire was not mentioned and felt left out yet again. Unfortunately it turned out that she was pregnant with Byron’s child. She confided in Shelley and Mary, and Shelley agreed to talk to his friend about it to find out what should happen with the child. Byron was not impressed, not even interested. He agreed that he would accept the child when it could leave its mother and that Claire could see the child whenever she wanted. At the time this declaration was made Claire seemed somewhat satisfied. Byron saw her as a common tart who had thrown herself at him until he finally responded – and who then wouldn’t leave him alone. He considered her far beneath him, both socially and intellectually.

After the Claire and Byron episode the friendship between the two groups cooled considerably. Shelley was not sure he liked Byron the man as much as he admired his poetry (is it possible he felt a pang of guilt in recognising his own behaviour towards Harriet in Byron’s for Claire). Shelley, Mary, their son William, and Claire returned to England. They settled for a time in Bath. Shelley commuted between there and London on writing and publishing business; Mary was engrossed in her novel and Claire, as usual, was feeling unwanted.

Out of the blue a letter arrived from Mary’s half-sister Fanny. She was desperate, she felt she had been left to look after her parents all alone. She felt used and abandoned; she threatened to kill herself. Shelley set out to find her and rescue her but he was too late. She had already taken an overdose of laudanum. It was shocking for everyone, no one expected such an outburst from Fanny or that she would act on her threat. She was buried in an unmarked grave.

Mary threw herself deeply into working on

Frankenstein

to help alleviate the pain and guilt caused by Fanny’s death. Claire wandered around bored and listless with pregnancy. In her own desperation Claire wrote to Byron, who eventually asked Shelley to tell her to stop pestering him. Then came the news that Harriet’s pregnant and partly decomposed corpse was found in the Serpentine in Hyde Park. She had left a suicide note that pleaded with Shelley to let the children stay with her sister Eliza, but if he were to take their son then he was to be kind to him. Shelley immediately reacted by going to the sister’s house and demanding custody of his children. If Harriet had not begged him to leave them with Eliza, whom he detested, then maybe he wouldn’t have considered uprooting them; more mouths to feed, more responsibility. But to be urged to leave them with the woman he hated was asking too much. Eliza would not let him in the house and refused to give up the children. Shelley threatened legal action, which he began to organise straightaway.

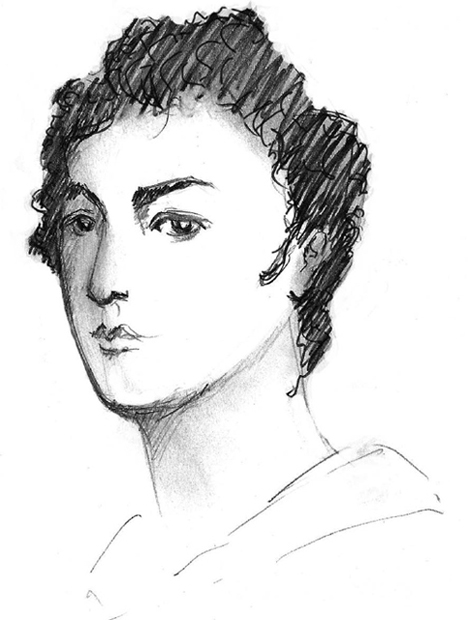

Byron

Harriet had been desperate. She loved her children but having been left by Shelley she had no future ahead of her. She could not marry again; she had to be dependent on her father (although Shelley eventually provided a £200 annual pension). She was shamed, lonely and, surprisingly, pregnant at the time of her death. It is now believed that the father of her unborn baby was Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Maxwell, who at the time of Harriet’s death was overseas. The story goes that his landlady refused to pass on his letters to Harriet because she knew it was an adulterous affair. Harriet believed she had been abandoned once more and could not stand the thought of it. It is pretty safe to say it was not Shelley’s child.

The only good thing that Harriet’s death brought about was that it meant Shelley and Mary could get married; an odd step for two people so adamant that they didn’t believe in the institution. Marry they did in a very quiet ceremony at the very end of December 1816. For his part, Shelley hoped that being married to his former mistress would help him get custody of his children by Harriet. Mary, although she may not have wanted to admit it, really wanted the stability of a monogamous relationship made with a legal procedure. With the marriage came permission to re-enter her father’s household. Shelley was able to purchase the lease on a house in Marlow and in January 1817 Claire had a baby girl whom she called Alba. At least with the arrival of baby Alba Claire seemed to settle down into the role of perfectly satisfied motherhood. For Shelley it was not such a good start to the year, as he lost his case for custody of his children. They were taken from Eliza and their grandfather and put into the care of a neutral party. Shelley didn’t see them again, although he was by law made to pay a regular amount for their care and upbringing.

Claire’s baby was followed by Mary’s whom they named Clara. Mary had finished her novel and Shelley had secured its publication. They had by this time settled into a fairly comfortable domestic group. It was only spoiled by Byron writing to demand his daughter be delivered to him in Italy. It upset them all. Claire was desperate to keep her beloved child; Shelley thought Byron a heartless brute and Mary did not see how a child as young as Alba could be sent all the way to Italy without people who loved her by her side. They planned and unplanned to take the child to Byron themselves. Also, by this time, Byron had insisted the girl be renamed Allegra.

The trip was finally settled and in 1818 the trio with three children went to Italy. Unfortunately little Clara Shelley, only a baby, came down with typhus and died. The Shelleys were left with little William, the son and heir. About nine months later he too got ill and died, he was only 3 years old. As seemed to be Mary’s way, she conceived another child after the death of little Clara; the baby was born after the death of his older brother. This child was named after his father, Percy, and Florence because that was the place of his birth. Percy Florence lived to old age, inheriting his father’s estates, though he was himself childless.

Allegra was duly delivered to Byron and Claire never saw her little girl again. Byron did not really want the bother of a child and when the little girl began to make demands on his time he had her given to the British-Consul General and his wife to look after. They were not too keen to have a man’s illegitimate child thrust upon them, and when they left Venice, Allegra was passed on to the Danish Consul and his wife. Finally the child, age 4, was sent to a convent in Ravenna where she died quite suddenly in 1822 of a ‘convulsive catarrhal attack’ thought to be either a form of typhus or recurring malaria; she was just 5 years old.

Shelley never forgave Byron for his callous disregard for the little girl who was taken from her mother as a form of punishment and no other reason. Even though he had abandoned a wife and two children himself, Shelley may have learnt the preciousness of what he had lost. Certainly he couldn’t understand why someone would act in the way Byron had done.

Claire finally settled down after the initial shock of her daughter’s death. She wanted to return to Florence, where she had been making her own life for once, but the Shelleys were organising for her to go to Lerici with Mary, who was pregnant for a fifth time. Claire did not really have a choice; she was still dependent on the Shelleys for her maintenance. It was probably just as well that she did go with them as Mary suffered a terrible miscarriage, bleeding so profusely that she could easily have died. Shelley was full of the fact that he had ordered his wife to be placed in a tub of ice to stem the blood flow, but it was most likely Claire who gave the emotional support Mary needed. A month later Mary Shelley was to become a widow. Her husband, his friend Edward Williams and a young Englishman, 18-year-old Charles Vivian, went out sailing and were caught in a storm. The boat went missing. Mary and Edward’s wife Jane had no idea that anything had gone wrong until several days later when they had no word from their husbands. They both went down to Livorno, where the boat had been heading, to meet with Leigh Hunt and Byron, who also had no idea that anything was wrong. Nearly two weeks after Shelley and his friends went out in the boat their bodies were found washed up on the coast.

Mary reacted to her husband’s death in a quiet and dignified manner that was thought cold by some of her friends. Claire was still with her for support, they had both loved Shelley in their own way. Now Mary had no income; she didn’t know if Shelley’s father would continue to pay the allowance he had granted his son. Mary was going to have to earn her living and, as far as she was concerned, so was Claire. The sisters’ bond was broken at last.

Claire did not seem to resent the fact that Mary couldn’t keep her. She took herself off to become a governess. Her first stop was to visit her brother Charles in Vienna. However, she felt unwelcome in Austria and when she was able to Claire took up a position with Countess Zotoff to educate her children in St Petersburg. Before she had left Italy Claire had found she was suddenly bombarded with offers of marriage and declarations of undying love from a number of different men of varying ages and incomes. She refused every one of them although she was penniless at the time. Perhaps, after being tied to her sister for so many years, Claire liked the idea of total independence and freedom from love and men. After spending time with the countess, Claire went further north into Russia, at which time none of the family heard from her for more than a year.

Mary stayed in Italy with the Hunt family, until she was encouraged by Byron to go back to England. She had decided to devote the rest of her life (she was sure she would die at the age of 36, like her mother) to putting Shelley’s papers in order and trying to get his poems published. She would keep herself and Percy by writing. After all, she was the author of

Frankenstein

and another novel,

Valperga

. In August 1823 Mary Shelley and her 3-year-old son were back in England. She eventually managed to get a £200 loan from her father-in-law that would be paid back out of her old man’s estate when he died.

Then suddenly Mary Shelley found she was a celebrity author herself.

Frankenstein

had been turned into a stage play and was drawing huge crowds. Her novel went into a second publication and her name became a household word. Thus Mary was able to devote much of her time on returning to England to editing Shelley’s work and enhancing his reputation as a kind and gentle man.

Mary became a noted novelist in her own right and lived to see her only son, Percy Florence Shelley, inherit his grandfather’s estates and marry a respectable widow of independent means, Jane Gibson St John. While the kindly Percy was happy to ramble about his estates, his wife was keen to secure the Shelley, Godwin, Wollstonecraft legacy and helped her mother-in-law with Shelley’s papers. Mary lived well beyond her self-predicted 36 years of age but she still died relatively young at 53 of a brain tumour.

Claire lived to be 80. She did not have an easy life after Shelley’s death but she did maintain her new-found independence. She worked in Russia for several years, but always in fear of being discovered to have socially unacceptable relations. After Byron’s death in 1824 Claire was anxious that one of the many biographies coming out about him would reveal her part in his life. Eventually word did get out and she then found it hard to get employment. She struggled on for twenty years working as a governess with one family or another.

In 1846 Shelley’s father finally died and Shelley’s kind legacy to Claire was made available to her. It meant she could give up teaching. She retired to Florence and spent much of her old age making sure that the facts about her youth shared with Shelley, Byron, Mary and other famous people was not mistold. She did claim, outrageously, that Byron had only pretended their daughter had died in order to upset her – and had sent the body of a goat in the coffin to England, not that of a child.

Claire Clairmont died in 1879.

Mistress as Muse