Otherwise (49 page)

There was another chair there like the one he sat in, and gingerly I lowered myself into it. “No,” I said, and felt a strange lump in my throat. “No, I didn’t know that; but now I do.”

“Yes,” he said. He looked at me curiously, nodding his head and sipping his soda. I allowed my arms to rest on the arms of the chair. I knew—though I was afraid, as yet, to let myself wholly believe it—that I had come to a place I had long sought, and could stay.

FOURTH FACET

FOURTH FACET

A

nd I thought, as that summer went on and I was not sent away, when I would come through the woods with water and see the tree house amid its speaking leaves, that perhaps Blink had found me just as I had found him: someone whom he had long waited for. I would smile at our luck even through the complicated task of getting myself up, and then the water up, and then the water inside and into Jug.

Jug on its table stood as high as my chin; made of plastic, bright yellow, sleek and edgeless. It had a top that fit snugly, which had once been clear but was now cloudy. Water from its little tap, though it had been standing all day, tasted as fresh and cool as though you drank it from the stream. Painted or somehow sealed on its front was a picture of a man, or a creature like a man, with thick square running legs and arms thrown wide. One fat hand held a glass from which orange liquid splashed; the other hand thrust up one clublike finger. His head, orange as the liquid in his glass, was immense for his body, a huge sphere, and bore an expression of wild glee, of unimaginable shrieking joy. That was Jug.

I asked if it was one of Blink’s souvenirs from the city. He had made a trip to the city when he was young, and he would tell stories about it at night. “I took it to carry the rest of the things I found,” he said, “because it was light and big. I strapped it to my shoulders.” And he would tell about the silent city, more silent than anywhere, because almost nothing lived there to make noise. In ancient times there had been not only the men but the populations that lived on men, birds and rats and insects; they all disappeared when the men left. He had walked through the silence, and climbed into buildings, and took Jug to carry the things he found.

When he told stories of the city and the things he had found there, I thought Blink might be Bones cord, or even Buckle, though Buckle cord has no saints at all in it. But I wasn’t satisfied with this. When I saw him with his specs on, at the table working at his crostic-words, absorbed in their mystery, and beautiful in his absorption, brushing away a fly and crossing and uncrossing his big feet in perplexity, I was sure he was of St. Gene’s tiny Thread cord. But still it wouldn’t do.

Why didn’t you ask him?

Ask him what?

What cord he was.

Well, if I didn’t know, how was he to know?

But

you knew what cord you were.

Yes. And if I had known St. Blink in the warren, with his friends and his occupations and the places he chose to live, I would have known what cord he was, too. Your cord, you see, isn’t something you discover just by examining yourself, the way you look into a mirror and discover you have red hair. In Little Belaire, you are in a cord, and a cord is—well, a

cord,

like a piece of string, not like a name you bear. That makes it clearer, doesn’t it?

Well. Just go on. What was it you said he was doing, so absorbed, that made you think he was Thread cord?

He was at his crostic-words.

When St. Ervin came to learn to be a saint from St. Maureen in her oak tree, he was never once allowed up into the house she had built there, never once, though he stayed for years. She would dispute with him sometimes, and tell him to go away and leave her alone; he wouldn’t go, he insisted on staying, he brought presents and she threw them away, he hid and she discovered him and ran him off with a stick, well, the story is very long, but the end is that when St. Maureen was dying and St. Ervin came to her as she lay too weak to run him off, and wept that he could not now ever be a saint, she said, “Well, Ervin, that’s a story; go tell that.” And died.

When I had been a few days in the tree house, I told Blink, in some embarrassment, why I had come, and like St. Maureen, he only said, “You want to be a saint? A saint? Then why are you here? Why don’t you be about it?”

“I thought,” I said, head down, “that maybe I could stay here with you, and listen and watch, and see how you became a saint, and learn to do the same.”

“Me?” he squeaked in consternation. “Me? Why, I’m not a saint! Whatever could have given you that idea? Me a saint! Boy, didn’t they teach you to speak truthfully in the warren? And couldn’t you have heard it in all I said? Do I sound to you like St. Roy?”

“Yes,” I said truthfully.

Abashed, he turned to look at his crostic-words. “No, no,” he said after a little thought. “I’ll tell you what. A saint will tell you stories of his life, and …”

“And so do you, about going to the city, and all the things you found there.”

“There’s a difference. The stories I tell are not of my life, but of our life, our life as men. It’s the difference between wisdom and knowledge. I’ll admit to knowledge, even to a lot of it, if it makes you happy to have found me; useless knowledge though it is. But wisdom—I’m no angel, I know this much, that wisdom need not come from knowledge, and sometimes can’t at all. If it’s knowledge you want, well, I haven’t had anybody to tell about it for years, so I’m glad you’ve come; if it’s wisdom, then you’d better be about it any way you can find; I’ll be no help.”

“Would it be possible to have knowledge and still be a saint?”

He hmmed a bit over that. “I suppose,” he said; “but being a saint wouldn’t have anything to do with how much knowledge you had. It would be like, you can be tall, or fat, or have blue eyes, and be a saint—you see?”

“Well,” I said, relieved, “maybe then I could start with getting knowledge, and take my chances with being wise as I go along.”

“It’s all right with me,” said my saint. “What would you like to know?”

“First of all,” I said, “what is it that you’re doing?”

“This? This is my crostic-words. Look.”

On the table where the morning sun could light it lay a thin sheet of glass. Below it was a paper, covered minutely with what I knew was printing; this took up most of the paper, except for one block, a box divided into smaller boxes, some black and some white. On the glass that covered the paper, Blink had made tiny black marks—letters, he called them—over the white boxes. The paper was crumbled and yellow, and over a part of it a brown stain ran.

“When I was a boy in Little Belaire,” he said, bending over it and brushing away a spider that sat like a letter above one white box, “I found this paper in a chest of Bones cord’s. Nobody, though, could tell me what it was, what the story was. One gossip said she thought it was a puzzle, you know, like St. Gene’s puzzles, but different. Another said it was a game, like Rings, but different. Now, I wouldn’t say it was only for this that I left Belaire to wander, but I thought I’d find out how it was a puzzle or a game, and how to solve it or play it. And I did, mostly, though that was sixty years ago, and it’s not finished yet.”

He ducked his head beneath the table and searched among the belongings he kept there. “I talked with a lot of people, went a long way. The first thing I found out was that to figure out my paper I had to learn to read writing. That was good advice, but for a long time no one I met knew how to do it.” He drew out a wooden box and opened it. Inside were dark, thick blocks that I had seen before. “That’s Book,” I said.

“Those are books,” said St. Blink.

“There’s a lot there,” I said.

“I’ve been places,” he said, lifting the top Book, “where books filled buildings as large almost as Little Belaire, floor to ceiling.” He lifted the cover to reveal the paper sewn up inside, which released the peculiar smell of Book, musty, papery, distinct. “The book,” he said slowly like a sleeptalker, drawing his finger under the largest writing, “about a thousand things.” His fingers wandered over the rest of the page, while he said “something something something” under his breath, and came to rest on a line of red writing at the bottom. “Time, life, books,” he said thoughtfully, and lowered the lid over it again.

“There are people,” he said, tapping the gray block, “and I found some of them eventually, who spend their whole lives with this, peeking into the secrets of the angels. They’re turned around, you see, and look backwards always; and though all I wanted to do was to solve my puzzle, the more I learned to read writing, the more I got turned around myself. It’s endless, the angels’ writing, they wrote down everything, down to the tiniest detail of how they did everything. And it’s all in books to be found.”

“You mean if we could read writing, we could do all those things again that they did? Fly?”

“Well. They had a phrase, they said, ‘Necessity is the mother of invention’; and I can imagine that there could come a time again when some inner necessity makes us begin all that again. But I can more easily imagine that all that is done with, put away in these books, like toys that don’t amuse you any longer but which are too much a part of your childhood to pitch out.

“Those old men, you know,” he said, putting away all the Book and sliding it back into place under the table, “they wouldn’t dream of actually trying to follow the instructions in any of the million instruction books. That it was once all like that is sufficient for them. That it could ever be like that again—well, it’s like smiling over the sadnesses of your youth, and being glad they’re all quite past.”

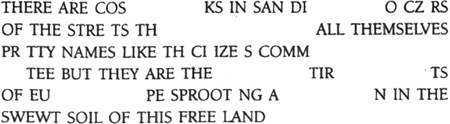

He bent again over his ancient puzzle. He sighed. He wet a finger and wiped a mar on the glass. “You put letters in the boxes,” he said, “according to instructions written here. But the instructions are the puzzle: they are clues only, to words which, when broken up into letters, will fill the empty boxes. When every clue has been deciphered, and the word it hints at guessed, and all the letters rearranged rightly and put in their proper boxes, the letters in the boxes will spell out a message. They will make sense as you read them across.”

That may not have been exactly what he said, because I didn’t ever really understand how it worked. But I understood why he had spent so many years at it: to have been hidden so well, what at last appeared in the boxes must be of vast importance. I looked down at what composed the message, filled with gaps like an old man’s mouth. “What does it say?”

He was

right, that it was a puzzle or a game; you were wrong to think it must be important, to be so well hidden. It was one of thousands like it; the angels solved them or played them in a few minutes, or an hour, and tossed them away.

Angels…. If I could believe only a part of what St. Blink told me, the hundred years or so before the Storm must have been the most exciting to be alive in since there have been men. I spent a lot of time daydreaming about those times, and what it would really have been like. The stories to furnish my daydreams poured out of Blink like water; I think he had been like me when he was young, and still was in a way, though he snorted when I talked about how wonderful it must have been. “Wonderful,” he said. “Do you know that one of the biggest causes of death in those days was people killing themselves?”

“How, killing themselves?”

“With weapons, like the ones I told you about; with poisons and drugs; by throwing themselves from high buildings; by employing oh any number of engines that the angels made for other reasons.”

“And they did that deliberately?”

“Deliberately.”

“Why?”

“For as many reasons as you have to say the time they lived in was wonderful.”

Well, there was no convincing me, of course; I would still sit and dream away the hot sleepy afternoons, thinking of the angels in their final agony, their incredible dreaming restless pride that covered the world with Road and flung Little Moon out to hang in the night sky and ended forcing them to leap to their deaths from high buildings still unsatisfied (though I thought perhaps Blink was wrong, and it was only that they thought they could fly).

Oh, the world was full in those days; it seemed so much more alive than these quiet times when a new thing could take many lifetimes to finish its long birth labors and the world stay the same for generations. In those days a thousand things began and ended in a single lifetime, great forces clashed and were swallowed up in other forces riding over them. It was like some monstrous race between destruction and perfection; as soon as some piece of world was conquered, after vast effort by millions, as when they built Road, the conquest would turn on the conquerors, as Road killed thousands in their cars; and in the same way, the mechanical dreams the angels made with great labor and inconceivable ingenuity, dreams broadcast on the air like milkweed seeds, all day long, passing invisibly through the air, through walls, through stone walls, through the very bodies of the angels themselves as they sat to await them, and appearing then before every angel simultaneously to warn or to instruct, one dream dreamed by all so that all could act in concert, until it was discovered that the dreams passing through their bodies were poisonous to them somehow, don’t ask me how, and millions were sickening and dying young and unable to bear children, but unable to stop the dreaming even when the dreams themselves warned them that the dreams were poisoning them, unable or afraid to wake and find themselves alone, until the Long League awakened the women and the women ceased to dream: and all this happening in one man’s lifetime.