Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine (17 page)

Read Ottoman Brothers: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Early Twentieth-Century Palestine Online

Authors: Michelle Campos

Tags: #kindle123

These rituals of revolutionary brotherhood led to expressions of a new discourse of the Ottoman nation.

Ottoman

became a term of self-identity; rather than referring solely to “them” —namely the bureaucratic ruling class—for the empire's many ethnic and religious groups Ottoman now referred to the first person plural: “we” and “us.” This first-person plural sentiment was already articulated in the first days by Mendel Kremer, the Jaffa-based correspondent for the Hebrew paper

The Observation (Ha-Hashkafa)

and an Ottomanized Jew: “Without a big mess or spilling of blood,

our people

had achieved the dearest thing possible”—a representative government.

79

As Kremer's articulation alluded, this imperial collective was to a great extent civic and recalled its base in political membership and citizenship rights. Phrases like “fellow citizens”

(vatandaşlar/muwātinīn)

, “Ottoman compatriots”

(muwātinīn ‘Uthmānīyīn)

, “all Ottomans,” and “dear voter(s)” were bandied around in speeches and articles as underscoring the core link between Ottomans.

At the same time, despite the fact that there was little pretense of an actual shared genealogical background that linked all Ottomans together, one of the cornerstones of primordial or ethnic nationalism,

the “Ottoman nation” was nonetheless discursively reformulated as a “family.”

80

The discursive formulation of an Ottoman family had existed before: the Greek Orthodox Constantin Adosside (1817-95) wrote an Ottoman language textbook for use among Greek Orthodox youth in which he used the expression “the great Ottoman family.”

81

However, the language of family and the corresponding implications of ties of kinship and mutual affection and obligation became much more widespread during the revolutionary era. In the words of one Jerusalemite, Avraham Elmaliach, in the euphoric first weeks “everyone felt they were brothers from birth, everyone danced together, everyone walked together arm in arm.”

82

Public speakers and newspapers alike appealed to their “Ottoman brotherhood” or “dear Ottoman brothers.”

In part, this bond of kinship and brotherhood was seen as having been born of the revolution, literally through the constitution and through the bonds of imperial citizenship. As one Jewish celebrant in Jerusalem, David Yellin (the older brother of Shlomo Yellin), noted, “Today we have reached that which was far and made familiar that which was strange, and justice comprises all of the Ottomans without difference to their rites or religions, and has turned them into one people henceforth in its progress and advancement.”

83

Months later, Yellin further elaborated the citizenship-kinship formulation of Ottoman brotherhood:

Thank God that tyranny and its men fell. Its replacement is unity and its beauty which caused the whole nation of the homeland to be brothers in one endeavor—the success of the homeland and its people and the pride of membership in one family: the Ottoman family. And who among us does not remember how the fire of brotherhood was kindled suddenly in the hearts of all the Ottomans, and how the whole nation experienced in one stroke the holy feeling—the feeling of unity to endeavor for the good of the country (and it is their country, all of them) and the success of the state (and it is their state without exception).

84

This Ottoman brotherhood was born of and suckled by constitutionalism, and as a result syncretistic phrases like “brother voter” combined civic Ottoman duties (voting) with the primordial language of kinship (brother). While brothers and families share blood running through their veins, the Ottoman civic brotherhood was born of the metaphorical mixing of its peoples. As the Muslim lawyer Ragheb al-Imam stated in Jerusalem, “The Ottoman races who were of different nations entered through the melting pot of the constitution [

būdaqat al-dustūr

] and came out as one bullion of pure gold which is Ottomanism, which unites the hearts of the

umma

and brings together their souls.”

85

In this metaphor of the melting pot, al-Imam was echoing Rashid Rida, who had declared months earlier that “all the groups (of the empire) mixed in

the melting pot of the basic law and became one bullion of gold which cannot be counterfeited and which does not rust.”

86

Ottoman brotherhood went even further to incorporate the classic nineteenth-century nationalist elements of blood, soil, and homeland, all of which would help overcome the superficial differences of religion, ethnic group, and language. The

watan

—homeland—emerged as a central trope in the revolutionary period, directly building on the sentiments of loyalty and patriotism that had begun to emerge decades earlier. The iconic works of Namik Kemal were republished several times in the years 1908-10. As the Cairene monthly

The Crescent (Al-Hilāl)

reminded its readers, “If the people know the meaning of

watan

in its true meaning, the greatest responsibility goes to Kemal Bey alone. Because [before him] everyone considered his

watan

the region where he was born, but Kemal Bey told them that the

watan

is the whole of the lands where their flag flutters and where their army defends and where their hearts beat.”

87

In the fall of 1908, performances of Kemal's famous play

Vatan yahut Silestre

were held throughout the empire.

88

According to newspaper accounts reporting on a Beirut performance in October, there had been much popular demand for his “story of the homeland.” The performance took place in the military courtyard with over two thousand Beirutis in attendance, including notables, intellectuals, and the army, as well as foreign consuls. The newspaper report stated that the climax of the performance came at the end of the play, when a soldier-actor visited the grave of the playwright Namik Kemal, the “nightingale” and “martyr” of liberty. Upon opening the tomb, Kemal emerged wearing a white shroud, and was “carried in the glory of liberty” by the soldiers present before returning to his grave and his now-peaceful, eternal rest.

89

The connection that Kemal had forged between homeland and patriot, or land and body, went through martyrdom. The “Homeland Poem”

(Vatan §iiri)

, performed in the play and sung in chorus by the cast, illustrates this well:

Wounds are medals on the brave's body

The grave [martyrdom] is the soldier's highest rank;

The earth is the same, above and underneath;

March, you brave ones, to defend the homeland.

90

This emphasis on the intimate union of territory and individual-collective—blood and soil—is particularly resonant for observers of modern nationalism. In the words of the theorist Anthony Smith, “The cult of the glorious dead gives the most tangible expression to the idea

of the nation as a sacred communion of the dead, the living and the yet unborn. But, more important, the cult of the glorious dead, and the rites and ceremonies of national commemoration that accompany it, are themselves seen and felt as sacred components of the nation, intrinsic to its ‘sacred communion' of history and destiny.”

91

Indeed, martyrdom became a prominent theme of the Ottoman revolution, not only retroactively describing Kemal, Midhat Pasha, and the other early liberals, but applying as well as to the soldiers and others who fell as “martyrs” in the cause of liberty throughout the events of 1908-9 and after.

In the fall of 1908 prayer services and commemorative ceremonies honoring the martyrs of liberty were held in mosques, churches, and synagogues throughout the empire. For example a ceremony was held in the Red Armenian Church in Pera (Istanbul), to which members of the Young Turk central committee were invited; the priests led a procession to the accompaniment of the Ottoman military band which played the Armenian national anthem.

92

Another Armenian church in Cairo held a ceremony in tribute to the “Ottoman martyrs of liberty [

shuhadā' al-hurriyya al-'Uthmānīyīn].”

Schoolchildren sang the Ottoman anthem and speeches were given in Armenian, Turkish, and Arabic for the standing-room-only crowd.

93

Another service in memory of the “martyrs of liberty” was organized by the Committee of the Union of Ottoman Women and held at the Yeni Cami (New Mosque) in Istanbul.

94

Later, the approximately seventy men who fell in the brief April 1909 anticonstitutional coup were rendered martyrs. The body of one of the members of parliament killed by the rioters, Muhammad Arslan, a notable Druze from Lattakia whose family demanded that his body be returned to Lebanon, was left unwashed by order of Shaykh Abdullah at the Gülhane hospital. The

shaykh

reportedly exclaimed: “For it is the body of a martyr and his blood is ‘lotion' enough!”

95

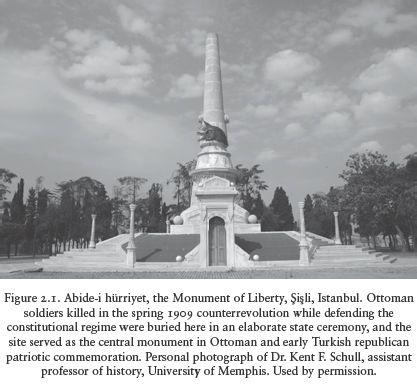

The remaining martyrs were buried in a collective grave in Istanbul in Şiş;li, which happened to be a mixed neighborhood with numerous churches, synagogues, and Christian and Jewish cemeteries. In the patriotic state burial service, CUP leaders emphasized that Muslims and Christians were lying side by side, a daring assertion that the law of patriotism and Ottomanism trumped religious law.

96

Later, a national monument was established on the site, called Abide-i hürriyet (Monument of Liberty), on which we see engraved: “the tomb of the martyrs of liberty [

maqbarat-i shuhada hürriyeti].”

This became the single most important site for Ottoman (and later early Turkish republican) constitutional and patriotic ideals, the location of the “national holiday”

(iyd-i milli)

ceremonies for almost a quarter of a century, as well as the site of various military parades and ceremonies.

97

Prime value was placed on this sentiment of self-sacrifice for the homeland in the press and in the revolutionary public sphere, a sentiment that would be pressed into constant service from 1911 onward as the Ottoman Empire engaged in three major wars before its final military enterprise, the First World War. Ottoman soldiers who fell in battle in Libya (1911), the Balkans (1912-13), and the First World War (1914-18) were accorded martyr status, both rhetorically and in terms of survivor benefits. Importantly, though, for many observers this martyrdom remained linked to the Ottoman citizenship project. Reuven Qattan, the Jewish poet from Izmir, expressed the value of national sacrifice in his two-part article “Our Line of Conduct: To Die and Kill for Liberty.” According to Qattan, the Ottoman government should know that “among its most sacred duties is to defend the natural rights of the nation, liberty and the constitution, and not to allow anything to touch these inviolable things. The nation prefers to kill the diseased dog. The nation prefers to die than to lose liberty.”

98

The political model of revolutionary brotherhood was a fulfillment of Namik Kemal's emancipation trade-off that he had offered decades earlier: in exchange for full equal rights in the Ottoman nation, non-Muslims were to give up their unique privileges and take on the duties of other Ottoman citizens. In other words, the theater of revolutionary brotherhood was premised on the expectation that all Ottomans would share not only rights but also obligations, and that all communities—being recast as Ottoman first and foremost—would work for the public good in a republican spirit of shared citizenship. This was presciently expressed by one public speaker who proclaimed that “from now on we will no longer hear another ‘Armenian,' ‘Muslim,' ‘Hebrew,' or ‘Christian,' but rather ‘Ottoman'! We're all brothers! We all need to work for the good of the homeland, and we hope that it will [in fact] be good.”

99

Along those lines, a similar sentiment was expressed in

The Lighthouse

newspaper: “On this day the Ottomans showed that they are an

umma

which has rights over its state, and their unity will bring it utility, and upon them are obligations and commitments to their government, and they have a law that treats them equally in its dealings, and they have a nationality that unites them irrespective of lineage, language, sect, and religion.”

100

Thus, to a great extent the “Ottoman

umma”

was premised on the underlying principle of civic nationhood, bounded by the legal borders of the Ottoman Empire, united in the mutual rights and obligations of Ottoman citizenship. This was explicitly articulated in the political program of the CUP, translated and republished widely in the Arabic press, which stated in Article 9: “Each person will enjoy complete liberty and equality irrespective of his race and sect, and is expected of the same things as each Ottoman irrespective of race and sect.”

101

More specifically, the CUP charged that “all the Ottoman subjects are equal before the law and have the right to government positions, and each individual who fulfills the conditions of competence will serve in the government according to his worth and competence just as the non-Muslim subjects will serve in the army.”