Outbreak! Plagues That Changed History (2 page)

Read Outbreak! Plagues That Changed History Online

Authors: Bryn Barnard

It took thousands of men and women working over many centuries to uncover the simple truths about infection we take for granted today. Of the many important names in the history of epidemics, a few stand out. First in line is an Italian physician, Girolamo Fracastoro, who in the early 1500s guessed that tiny, unseen

seminaria contagium

(seeds of contagion) might spread disease. More famous is the Dutch cloth merchant and amateur lens grinder Antoni van Leeuwenhoek. In 1674, with his own homemade microscope, he became the first person to see and describe microbes, the first person to truly comprehend the existence of this previously invisible world. He called these new creatures

animalcules

. But he did not link them to disease.

Antoni van Leeuwenhoek was the first person to see and describe bacteria.

Two centuries after Leeuwenhoek, people still didn’t think microbes caused sickness. They knew microbes existed. They knew they were present on wounds and other injury sites. But microbes were perceived as a by-product of illness. By 1865, French chemist Louis Pasteur had made the critical breakthrough: he proved that microbes actually

cause

infection. He called them

germs

. Pasteur’s “germ theory of disease” opened the doors to understanding how illnesses are contracted and spread. His method of killing pathogens with heat—

pasteurization

—is still used to make many foods safe to consume. By 1884, Pasteur’s German rival, Robert Koch, had developed a method for testing the microbe-disease connection. His Koch Postulates are still the gold standard for determining whether a microbe causes illness.

Over the decades that followed, the competition between Koch, Pasteur, their students, and their rivals unraveled the mysteries of one infectious disease after another. The thresholds these explorers crossed made it possible for their successors to produce today’s medical miracles: antibiotics and vaccines, organ transplants and gene therapy, low infant mortality and high population growth. Slowly, scientist by scientist, revelation by revelation, the veil was lifted and our perception of pathogens changed. Looking for the invisible hand guiding our destiny? You can track it in the economy, find it in holy scripture, or sense it in the grand sweep of the stars. But there’s another truth, a different truth, a smaller truth. It’s closer than you think. Just look in a microscope.

Great epidemics, like wars, natural disasters, and other catastrophes, can expose the fragility of human society. Given enough stress, what seems the most solid and immobile social system can shatter. Such was the case in fourteenth-century Europe, a frozen society built on vast inequality and limited social mobility. For nearly a thousand years, Europeans were held in the rigid, unyielding grip of two interconnected forces: the feudal aristocracy and the Catholic Church. A third group, the knights, enforced their will. These power centers controlled all the wealth, owned all the land, determined all the laws, and were gatekeepers of all knowledge. They ruled over a body of ill-paid, ill-housed, illiterate peasant serfs, who did the work. Compared to competing regions like the inquisitive and inventive realm of golden age Islam or the continent-spanning empire of the Mongols, Europe was a Podunk backwater.

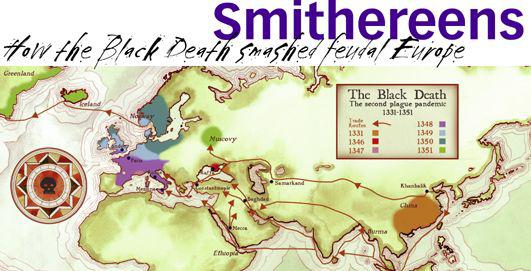

The arrival in 1346 of a new disease changed this situation. Arcing across Europe from the Medi-terranean to Scandinavia, the epidemic caused victims to become feverish and grow painful black welts that exuded a nauseating stench. Half who were sickened by the illness died. Europeans called it the Great Mortality, the Pestilence, and the Pest. We call it the Black Death. In four years, it destroyed a third of Europe’s population. Afterward, nothing in Europe was quite the same. The entire structure of European society became more porous, more mobile. With fewer workers, wages went up. With fewer consumers, prices went down. In both the countryside and the cities, a rising middle class was able to accumulate, at bargain prices, the land, businesses, and wealth the dead had left behind. This economic revolution in turn sparked other changes: in law (to make sense of the new order), in the arts (to reflect on the horror and show off the new money), and in trade (to accumulate even more). In the Church, the catastrophe smashed an ossified orthodoxy, leading to questions, inventions, heresy, wars, and ultimately a world with not one Christianity but many. Finally, in the world of the nobility, the social, economic, and political crises caused by the Black Death were blows from which the ruling classes never fully recovered. Bit by bit, their power seeped away to others, never to return.

Even before the arrival of the Black Death, Europe was heading for a brick wall of trouble. By the beginning of the fourteenth century, the population had grown to an unprecedented seventy-three million. Cities were crowded and filthy, filled with people who hardly ever bathed. Sewerage was inadequate, so rotting garbage and human waste were heaped in streets or dumped in rivers. Moreover, around 1280, the climate had begun cooling. Summers became shorter, winters harsher, and harvests worse. Nearly all the forests had been cut down. No more farmland

was available. People began to starve. Pessimism and persecution grew.

Adaptation to changing conditions was difficult, for the Church discouraged innovation and independent ideas. Priests enforced unswerving loyalty to the Pope and belief in orthodox Christian dogma. This included the conviction that we were born with original sin and lived cursed. Illness, like all of life’s troubles, was the result of sin. Christians dared not waver from these teachings. They risked excommunication or worse.

Medical knowledge had also stalled. Since 1300, Pope Boniface VIII had forbidden the dissection of human cadavers (pigs were used instead). Human anatomy remained a mystery. The function of many organs, even the circulation of the blood, was unknown. Physicians continued to depend on the thousand-year-old teachings of the fifth-century-

B.C.

Greek physician Hippocrates and his second-century-

A.D.

Roman follower Galen. These two influential doctors believed that illness was caused by an imbalance in bodily “humors.” An excess of hot blood, for example, was thought to cause fever. It was curable by phlebotomy: bloodletting. This approach to human health would prove utterly useless in combating the plague. Physicians did their best with the tools at their disposal, but for the most part they could only watch helplessly as their patients died.

To protect themselves from the Black Death, physicians wore a special outfit: a waxed-linen robe, a wide-brimmed hat, gloves, and a mask that featured glass lenses and a long beak filled with vinegar-soaked cloth and spices to counteract the stench of dying patients. Their preferred way of trying to cure patients was by bleeding them.

The Black Death probably started in 1331 in Central Asia, carried there by infected Mongol troops returning from Burma. By 1346, having killed millions and traveled with armies and traders along the Silk Road, the epidemic arrived on the Black Sea’s Crimean Peninsula. There a Tartar army was besieging the city of Kaffa. To break the city’s defenses, the attackers catapulted diseased corpses over the walls. Genoese merchants trading there fled via ship to Messina, Sicily. Sick and dying, they arrived in October 1347, bringing plague to the Italian peninsula.

Nearly everywhere the plague reached, victims died faster than they could be buried. In Pisa, five hundred people a day died. In Paris, eight hundred a day died. In Vienna, six hundred a day died. In Avignon, when the graveyards were filled, corpses were dumped in the Rhône River. In Bordeaux, rotting cadavers were stacked on the docks and in the streets. By December 1348, the epidemic arrived in England. Bodies there overflowed mass graves. It soon spread to Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Prussia, Iceland, and even distant Greenland. In 1351, when the epidemic seemed to be finally over, officials of Pope Clement VI estimated that 23,840,000 people were gone. Nearly a third of Europe’s population had been killed by the disease.

What was the Black Death? The most common explanation for the epidemic is bubonic plague, a disease passed to people by rodents. Historically, plague had been confined to populations of rats in isolated mountain regions, one in South Asia and the other in East Africa. When human activities like war and trade disturbed these ancient reservoirs, the plague escaped its natural confines. The devastating Justinian’s Plague that hit the Mediterranean in

A.D.

542 was likely bubonic, imported by Roman soldiers returning from Ethiopia. The Roman Empire never recovered, and European power shifted north; a century later, Islam became the predominant civilization of the eastern Mediterranean. The World Health Organization calls this the first plague pandemic. The Black Death was the beginning of the second. In all, that second pandemic lasted over three hundred years. Plague returned several times in the 1500s, struck London in the Great Plague of 1664–66, and finally sputtered out in the 1750s.

Plague is caused by a bacterium called

Yersinia

pestis,

named after the student of Pasteur who discovered it in 1894, Alexander Yersin. This microbe is a parasite that lives in fleas that live on rodents. These animals—fleas and rodents—are

vectors

(transmitters) of the disease. If an infected flea jumps from a rodent host and bites a person, it injects thousands of plague bacteria into the wound. They travel through the body’s lymph system to nodes in the groin and armpits, excreting toxins that kill human cells. As the body’s immune system tries to destroy the invaders, the skin blackens and the nodes swell into the disease’s characteristic buboes (from the Greek

boubon,

“groin,” thus the term “bubonic plague”). This isn’t the worst of it. Victims get feverish and suffer from vomiting, bouts of diarrhea, and respiratory distress before recovering or dying. If the bacteria migrate

to the lungs (pneumonic plague), death is virtually certain. A victim who breathes in

Yersinia pestis

from a bacteria-loaded cough can die within hours.