Outbreak! Plagues That Changed History (4 page)

Read Outbreak! Plagues That Changed History Online

Authors: Bryn Barnard

Europe’s decisive (albeit unwitting) advantage was disease. The explorers brimmed with pathogens to which the Native Americans had no immunity: hepatitis, influenza, typhus, typhoid, diphtheria, measles, mumps, and smallpox. The arrival of the Europeans was like the detonation of a biological bomb. In two generations, the majority of Americans (population

guesstimates range from ten to one hundred million) were dead. In two centuries, their cultures had been almost completely replaced by “neo-Europes”—not just European people and European culture, but European clover and honeybees, crops and weeds, cattle, horses, dogs, cats, and birds. Later, the same phenomenon was accomplished in Australia and New Zealand.

Of all the diseases Europeans introduced to the Americas and other new worlds, smallpox had the most devastating impact, killing more Native Americans than any other illness. Smallpox attacks the skin, internal organs, throat, and eyes. It causes a fever, headache, rash, and masses of painful, pus-filled bumps called pustules. From 30 to 90 percent of those who get smallpox die. For hosts who survive, the pustules scab over and fall off, leaving deeply pitted scars, possible blindness, and lifelong immunity to the virus. Smallpox was the decisive factor in the Spanish conquest of Mexico and Peru and the Portuguese invasion of Brazil, sowing confusion and terror among the defenders and reducing their numerical superiority. Later, smallpox swept across North America ahead of French and British colonists, emptying the land for occupation by the invaders. Given the terrible nature of the illness and the high mortality, it is remarkable Native Americans were able to offer any resistance at all.

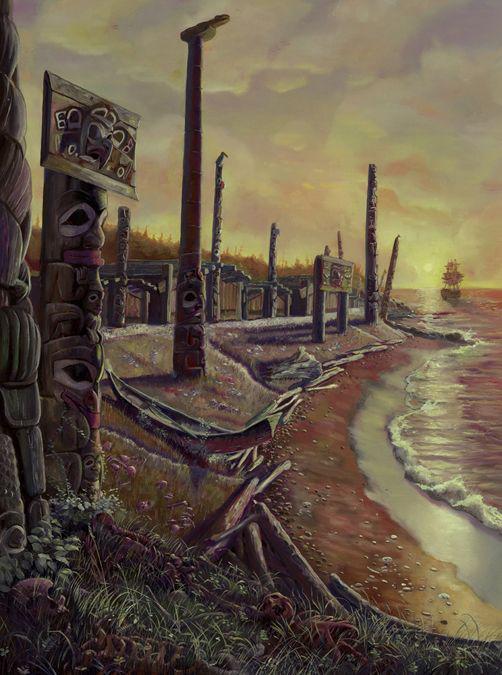

Smallpox raced across North America, depopulating the continent ahead of European colonists. In the Pacific Northwest, the Native American villages of Puget Sound were emptied of inhabitants well before George Vancouver arrived to explore the land for England.

Smallpox is believed to have originated in Africa thousands of years ago. The first recorded instance was during a war between the Egyptians and the Hittites in 1350

B.C.

It spread from there to Persia, India, and China. Both the Indians and the Chinese worshiped their own versions of a smallpox goddess, to whom they prayed for deliverance. Europe’s first contact with smallpox may have been Greece’s devastating Plague of Athens, which appeared in 430

B.C.

It killed the great orator Pericles and brought down the Athenian Empire. Continental smallpox epidemics did not appear until the Crusades in the tenth to fourteenth centuries, when thousands of European warriors in-advertently brought smallpox back from their invasions of the Middle East. By the time of Columbus’s voyage, smallpox was endemic in Europe. An epidemic in Paris in 1438 killed 50,000 people, mostly children.

After Columbus arrived on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, his reports back to Europe suggested paradise. The island’s Taino inhabitants had no monarchy and little hierarchy, a concept that flabbergasted Europeans. (Philosopher John Locke would later write, “In the beginning, all the world was America.”) The Spanish set to work to destroy this Eden. They forced the Taino to serve as beasts of burden. They took their food. They made them search for gold. They shot them for sport. Finally, they fed the corpses to their dogs. By 1516, when smallpox first appeared on Hispaniola, Spanish cruelty had reduced the indigenous population from an estimated two million to eight million to a mere 12,000. Smallpox finished the job. In 1510, the Spanish began importing African slave replacements. By 1555, the Taino were nearly extinct.

The Taino, like other Native Americans, had no immunity to European disease for several reasons. First, they were descended from Siberian immigrants. Thousands of years before, the ancestors of most Native Americans had walked across the frozen Bering Strait through the Arctic’s frigid decontamination zone. Pathogens accustomed to balmier climes couldn’t survive the journey and were left behind. Second, unlike Europeans, Native Americans didn’t keep much livestock. Domesticated animals are the source of many lethal human illnesses, including tuberculosis, influenza, measles, and smallpox. The Native Americans had neither many animal candidates for domestication, nor a useful version of the wheel to put them to work. Finally, the Americans had far better hygiene than the Europeans. They bathed regularly and kept their villages and cities clean, reducing contact with potential pathogens. They were tall, healthy, long-lived, and utterly defenseless.

One of the most infamous smallpox episodes occurred during the Spanish conquest of Mexico. In 1519, Hernán Cortés led a band of 550 conquistadors from Cuba to the Mexican mainland. Their goal was Tenochtitlán, capital of the Aztec Empire, a city rumored to be awash in gold. Cortés’s group reached the city in November. The emperor, Montezuma, welcomed the Spanish as descendants of the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl. In return, Cortés captured Mon-tezuma, ransomed him for gold, then tried to rule the Aztecs through him. By this time (the spring of 1520), a rival Spanish expedition led by Pánfilo de

Narváez had arrived in Mexico. One of Narváez’s crew had smallpox. Cortés left the capital to repel this rival. In the battle between the two invaders, one of Cortés’s soldiers became infected.

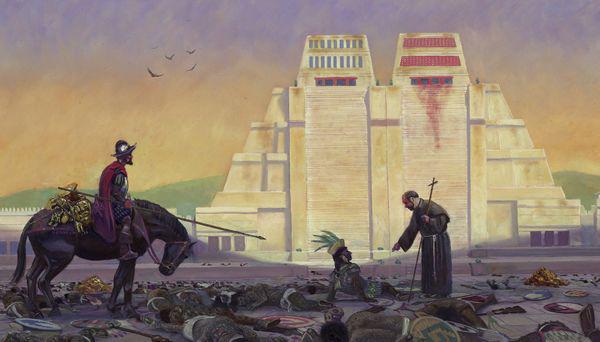

During Hernán Cortés’s conquest of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán, smallpox killed a quarter of the capital’s population within a few weeks. Although many of the demoralized survivors abandoned their gods and embraced Christianity, they continued dying from the disease.

The Aztecs, who outnumbered the Spanish a hundred to one, revolted during Cortés’s absence and defeated him upon his return. The Spanish fled for their lives. During the fighting, however, at least one of the Aztecs caught smallpox from the Spanish. A devastating epidemic broke out among the natives. Within a few weeks, a quarter of the capital’s population was dead, including Montezuma and much of the army. The corpses littered the ground “like bedbugs.” When Cortés regrouped and returned, the Spanish easily beat the demoralized survivors. The Aztec Empire was finished.

“Virgin soil” epidemics like this occurred wherever the Europeans set foot in the Americas. By 1527, the disease had spread south to the Inca Empire, killing the emperor and about 100,000 of his subjects. The epidemic sparked a civil war that had barely ended in 1532 when Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro arrived with about six hundred men. They captured the new emperor, Atahuallpa, ransomed him for a roomful of gold, then killed him. By chance, they also imported a second smallpox epidemic that killed so many Incans that fields were left uncultivated. Still more people died of famine. By the end of the sixteenth century, three-quarters of the Incans were dead. Meanwhile, in Brazil, the Portuguese were introducing the natives of the Amazon to Christianity and smallpox. The Indians died by the tens of thousands. Across the Americas, conqueror and conquered agreed that God was on the side of the invulnerable Europeans. It perplexed religious leaders, however, that though terrified natives converted to Christianity in droves, smallpox kept killing them.

Smallpox was essential to the English and French conquest of North America. In 1617, three years before the arrival of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, a virgin soil epidemic passed through what would become New England, killing 90 to 94 percent of the inhabitants. The Pilgrims found a nearly empty land of abandoned villages and fields covered with the bones of the dead. Smallpox returned again and again, making the first fifty years of British colonization a virtual cakewalk: they could take what they wanted with little resistance. No wonder King George III called the disease “the Blessed Pox.” Smallpox moved westward across the continent ahead of the pioneers in a great wave of death.

These epidemics were not always accidental. In 1763, during the final years of the French and Indian Wars, General Jeffrey Amherst, commander of the

British forces, recommended a gift of smallpox-laced blankets to jumpstart an epidemic among Native Americans. His goal was genocide, or as he put it, to “… Extirpate this Execrable Race.” This is only the most notorious instance of British and American biological warfare against the natives.

By the time English explorer George Vancouver cruised Puget Sound in 1792, the villages there were deserted, the beaches littered with skeletons. Smallpox had crossed the continent ahead of him.

Unlike the plague bacterium, smallpox is a virus that has no host other than humans. An epidemic can only spread from person to person. In the densely populated cities of Europe, smallpox moved through the population at a pace that ensured someone was always infected, so that each new generation of susceptible babies got exposed. In this continuous “chain of infection,” one got the disease, passed it on, and survived or died. Most city folk who made it to adulthood were invulnerable to smallpox outbreaks for the rest of their lives.

After the first generation of colonists established themselves in the New World, smallpox became nearly as bad a problem for their children as it was for the natives they were trying to exterminate. America’s colonial settlements were sparsely populated. Once smallpox had burned through all the susceptible people in a rural community, the chain of infection was broken. Smallpox could vanish completely for a generation. Only after enough vulnerable new hosts were born would a chance encounter with an infected individual start another epidemic. Between 1636 and 1717, Boston suffered seven separate smallpox epidemics.

Europeans tried the usual unproductive methods to stop smallpox—bleeding, enemas, purgatives, and prayer. They also used quarantine to some effect. But Asia and Africa already had a preventative that worked. For centuries, the Chinese had been using inoculation: deliberate infection with smallpox to create a mild form of the illness. In the Chinese procedure, smallpox scabs were ground into powder and blown up a person’s nose. Indians, Africans, and Turks used another variant: injecting scab power or smallpox pus directly into a wound in the skin. Either way, the patient would get sick, recover, and be immune for life. Inoculation had disadvantages: once inoculated, a person was fully infectious and could get others sick. Worse, one in fifty would die—not great odds, but better than those of an actual epidemic.

Variolization was practiced for centuries in the Far East, the Middle East, and Africa before the Europeans adopted the technique to immunize people against smallpox. In the Chinese version, dried smallpox scabs were blown up a patient’s nose, causing a mild case of the illness. People so treated had a one-in-fifty chance of dying. Survivors were immune for life.