Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind (32 page)

Read Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind Online

Authors: Sarah Wildman

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Cultural Heritage, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Jewish

Dr. Stern was born in Romania and immigrated to Germany in 1975, when he was twenty-four. His own father survived Auschwitz as a teen and would never speak of the experience; his paternal grandmother and aunt survived, but his grandfather and uncle were murdered.

“I’ve heard some stories from my father,” says Dr. Stern. We are sitting in a second-floor doctor’s lounge with brightly colored faux-leather seats. “But there are these experiences, they went so very deep and were so intense that—you know when you cook a soup with a pressure cooker? And if you open it when it’s boiling—well, you can’t. You have to wait till it cools down so there is no explosion. I’m convinced these experiences went on boiling in these people—but it was possible for them to go on living by keeping closed down. Because if you were to open it would be a kind of an emotional explosion that

would sap you of your strength to live. But his second wife told me that he woke at night––sweating and shouting. He never told us what was in those dreams.”

Stern explains some of what I already know from reading. “The Jewish Hospital was the only Jewish institution in Germany when all other institutions were closed. This hospital never stopped work as a hospital; and during the war, all during the war, there were still Jewish doctors treating patients. . . . They weren’t called doctors, they were called ‘Jew healers.’ It was a multifunctional place, this hospital. It worked as a hospital but also as a deportation camp.”

He means a transit camp. When the deportations began, he says, from the train station in Grunewald, “those Jews who were sick or couldn’t travel” were set aside. The Gestapo, of course, “didn’t tell them they would be deported to be murdered. It was said it was deportation for work.” But if people told the Gestapo they were sick, they were investigated by doctors or nurses at the Grunewald train station. If a person was sick enough, he would be taken for treatment and brief convalescence at the Jewish Hospital “to make him fit for the next journey.” The doctors and nurses would

cure

people in order to murder them later.

The Gestapo had a station at the hospital. “It was part of the hospital,” Stern says. “It was a prison.” The Gestapo would come and ask the doctors for a list of who was fit enough to go to the camp. “And if the doctor said, ‘I’m sorry, they are not fit enough,’ or ‘I have nobody,’ [what people told me was] the Gestapo would then say, ‘Okay, maybe I take your uncle or your aunt or someone of your relatives.’”

After the war, the hospital became the center of the remaining Jewish community. The first postwar bar mitzvah was held here. Stern tells me that in 2006, at the 250th anniversary of the hospital, a handful of nurses who worked through the war came back. They told the current hospital staff stories of work under occupation—and about Dr. Walter Lustig, the Jewish director of the hospital, who ruled like a little king. He has been described as having been something of a pig,

Lustig; he regularly took nurses to bed, controlling, as he did, everyone’s destiny, so that few felt they could refuse. (“We called him the

Schlächter

. The slaughterer,” Inge Deutschkron told me, indicating that everyone in the remaining Jewish community knew of him. She, too, spoke, with disgust, of his sexual exploits.) Eventually he took the helm of the Reichsvereinigung. At the end of the war, he disappeared.

It was rumored that he was killed by the Soviets for collaboration. In truth, no one knows.

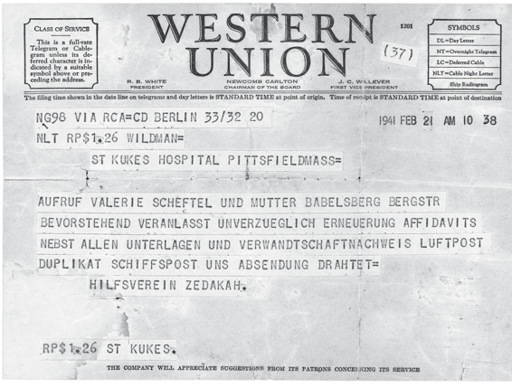

WESTERN UNION TELEGRAM

FEBRUARY 21, 1941

TO: WILDMAN, [ST. LUKE’S] HOSPITAL, PITTSFIELD, MASS.

TELEPHONE CALL VALERIE SCHEFTEL AND MOTHER BABELSBERG

BERGSTR. IMPENDING—INITIATE IMMEDIATELY RENEWAL OF

AFFIDAVITS PLUS OTHER DOCUMENTATION AND PROOF OF

RELATIONSHIP AIR MAIL DUPLICATE SHIP MAIL—CABLE TO US RE

SHIPMENT

AID ORGANIZATION ZEDAKAH

These days, unlike when Valy worked there, the hospital no longer has a children’s ward. When I ask to see what still exists, and operates, in the same manner as it did when she was here, Stern suggests we walk over to the small chapel on the campus of the hospital. It is a synagogue, nominally; there are cardboard-bound slim prayer books and small

kippot

waiting for those who would like to pray, though there is no longer a Torah scroll here: the

aron kodesh

, the small cupboard that keeps the Torah, is empty and the ceiling is peeling in places. It is no longer specifically Jewish, I suppose, more like those “prayer rooms” one sees in hospitals everywhere, or in airports. What remains is the shape of the room, a hint of its former life; on the wall there is a Jewish star, and the shape and structure and texts of a Jewish prayer hall.

In the early months of 1941, people were still leaving the hospital nearly daily, fleeing on the last trains and boats out of Germany; it was a scramble, it was awful, but it still seemed—however remotely—possible that emigration could happen. Valy clings to the hope of boarding a ship and sailing away from this nightmare.

[Spring 1941]

Dear, dear boy,

Today I have to write to you again. It is so sad that by now our correspondence has come down to an exchange of letters only on certain occasions. It is much, much more than just sad. You don’t know how awful this is for me. But, my darling, do not think that I am reproaching you. I know that three years is an awfully long time! So much can happen during that time! And one can have so many experiences! A long, long time ago you wrote to me from Vienna, when I was supposed to go to Prague, that one should not be so small-minded to sacrifice the present to the phantom of the future. You wrote these words in a completely different context at the time. But you were so right then! And maybe that’s your thinking right now as well. And maybe you are right in not wanting to sacrifice your present either to the past or to the future. It is, however, so terribly sad for me because I live almost without a present, and I can live only for the past and for the future!

But, darling, I can understand! Especially right now I really can understand as I have just had a passing experience that showed me how strongly the present can demand its right from us. But, as I said, this experience touched me only lightly and everything was nipped in the bud. It was a man who often reminded me of you. He was a bit like you, somewhat older, quieter, a little less genial, but perhaps a bit kinder. But he is not free and I, too, still do not feel free enough and therefore we did not live the experience to the fullest. Therefore, Karl, I could understand everything, although it would make me incredibly sad! What I find almost impossible to understand, however, is the fact that you don’t write about anything at all!

I have wanted to write this to you for a long time.

The immediate reason for today’s letter, however, is our emigration. As you will have learned from the cable that was sent three months ago, the matter now has become current, thankfully. Whether it will be doable, however, is another, far less simple matter. A couple of days ago we received another affidavit from Dr. Feldschuh that we will pass on immediately. Hopefully, it will suffice for the two of us! Because we do hope that dear mama and I will be able to emigrate together. Now the additional, very important question of the passage arises. It is of the utmost importance that two passages be booked on a certain vessel and for a certain date to the U.S.A. It would be possible to deposit a down payment from the US; the rest could be taken care of from here. What is really important, however, is that they be reserved and secure places! From here I cannot judge which shipping company would be feasible. I have learned that the American line is sold out until February of 42. Starting from September, there may be places available with the Spanish–Portuguese line, but I don’t know whether this is certain. If there is a possibility via Sweden, I think this would be best, although it supposedly is very expensive. Please contact Uncle Isiu and Dolfi Feldschuh from Vienna. We have also written to both of them/please make it possible for us to get out of here, as well. Maybe you could also consult with Alfred Jospe. He cannot do anything financially, but maybe he has some good advice. He is currently trying to get some of his relatives out, and maybe he has already got some experience. I will also write to him. Darling, many, many thanks for all your effort and please, please do not get tired and let up on your efforts! . . .

Unfortunately, I don’t have much good to tell you about my work right now. A couple of days ago, alas, I returned from the course I had written to you about. It was quite wonderful! Full of youth, spirit and verve! For the first time, since Vienna, I again felt glad and young! Now it has finally come to an end, unfortunately. I did a lot of teaching there and I believe that I have become a well-respected teaching authority there—your legacy, Karl! Upon my return, I unfortunately had to learn that I no longer can continue my work at the hospital and at the seminary for kindergarten teachers due to a general cut in positions. If I do not succeed in becoming confirmed as an itinerant teacher for various retraining facilities, I will have to start working in a factory before too long.

Well, darling, this letter was not too exhaustive, was it? Now you know everything about me—really everything and honestly told. Just the way you always wanted it! And I don’t know a thing about you! Don’t you think I should know of the things that matter to you and thus also to me?! . . .

Farewell, darling! And many, many kisses from

Your Valy

This letter lays me low every time I read it, both in its devastatingly perfect mimicry of my grandfather’s manner of speech—

one should not be so small-minded to sacrifice the present to the phantom of the future—

and in its stark narration of a moment of pleasure she denies herself. Valy had a passing—what? Infatuation? Dalliance? It’s hard to say exactly: she had a passing love interest—a crush!—that she let pass in part because the man was married, in part because of Karl. I read and reread, trying to decide if Valy is still in love with Karl, or if Karl is simply the only lifeline she has, and therefore she mistakes desperation for love.

When I read it with a German journalist, Katrin, she sighs; she is sure of Valy’s intentions. “Because I still love you—that’s what she means here clearly, she’s still in love, so nothing came of the man she met.” I tell her that I’ve shown this letter to other native German speakers and some disagree—my friend Uli in Kassel, for example, thinks this is not a love letter at all, that it is merely her means of trying to free herself from the Nazi yoke, that my grandfather was nothing more than a life preserver by this point. Katrin scoffs at that; she thinks my grandfather has given up on Valy, but the reverse is not true. “I think she knows it’s over. Obviously Uli has never received a love letter. This is the sort of letter you write when you’re trying to revive memories. This is something you do when you want to win someone back. These are not the words of a lady who feels she is loved back. She is unsure. . . .”

It has been three years now since Karl has seen Valy; three years since he last heard her voice. He is twenty-nine years old; they had not made a commitment to each other; he has dated other women. But somehow I wished for him to be a bit purer, perhaps. It is unfair, and unrealistic. She is twenty-nine, too, but she is so much older than that now. As she tells him:

“I again felt glad and young”

—they have aged rapidly, the young people left in the Reich.

But worse, even, than Valy denying herself the chance to be with someone else is her belief that the waiting has not been in vain. The possibility of emigrating grows dimmer and dimmer. But it is the only

option. Valy and her mother request additional papers from my grandfather. They ask for more and more. She has no sense of what my grandfather can, or can’t, do—money-wise, influence-wise. But she implies her quota number had come due, that her affidavits—requested multiple times and sent, somehow, by members of my grandfather’s extended family—were in order. The only thing left was to secure seats on a ship. Just tickets! Just seats! The problem was: that in and of itself was nearly impossible. And neither she nor my grandfather knew just how difficult it would be.

Even if everything else had been in order, the challenges facing my grandfather and Valy went far beyond the sorry state of his finances, or even the status of her affidavits; they were diplomatic and policy driven, and they came from the other side of the world from where she sat, desperate, in her room.