Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind (36 page)

Read Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind Online

Authors: Sarah Wildman

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Cultural Heritage, #Personal Memoirs, #History, #Jewish

Due to the age limitations, however, it may look pretty hopeless for me. But maybe, if we belonged together officially, this would be a possibility? I never wanted to propose this to you, and I really never ever wanted to talk about this again. But do you remember, my dearest one, once upon a time when you were with us in Troppau, you asked me what I wished for, and said that you wanted to fulfill my every wish. And then I wished so much for us to be together forever; but I did not want to take advantage of the situation, because I wanted you to make your own decision freely. Therefore, I did not say anything then. But today I believe I must tell you, if you really want me to be with you and if I did understand your last letter correctly. Karl, I ask you not to misunderstand me! Naturally, I would only want you to make your own free decision, even today. But the issue seems particularly relevant today and that’s why I put it forward “for discussion.”

I don’t want to write much more today. I hope to be able to write again next week. Now I have to go to my charge. He is so patient and grateful, highly educated and very bright. Today he presented me with an edition of “Faust.” He is, however, very challenging to deal with. Yesterday he fell straight on his face in the street, and I had to get help in order to get him up again. He is completely helpless sitting up and in bed, and he needs to be cared for right down to the smallest little detail. He is such a poor guy!

Every day I am waiting for your mail! If I only had a letter from you soon again! Please don’t let me wait too long!

How is your dear mama, and how are Zilli and Karl? Please give my regards to everyone.

Many, many kisses, my beloved

Your Valy

Here she has prostrated herself,

“I never wanted to propose this”

—she has done what she promised herself she would never do, she has asked him to marry her, to take her away from all this by making their relationship “official.” But it is 1941. A marriage, had it even been possible, had it even been what he wanted at that point, would not have been enough to pull her from the nightmare. And yet the humiliation is worth it, even for that sliver of a chance, even for the slightest hope it might bring her, even in just the proposal.

Writing is the only thing that keeps her sane. And yet now her writing has almost the quality of a fever dream:

10-31-41

My very dearest one,

. . . For the time being, thanks be to God, my situation remains unchanged. In the past I always resisted nursing work, or, at least, I was convinced that I would be really bad at it. Now it turns out that I am actually pretty good at it. At least, my charges seem very happy and wish God’s blessings upon me. If their wish only were to become reality and I could already be with you! Because this is my sole and only, my great, big desire for God’s blessing. Then I would be happy. I do not have any personal ambitions. Medicine means a lot to me. My station doctor used to laugh about the enthusiasm and joy with which I used to approach every new case. But you mean so much, much more to me!!! There really is no comparison—as I have often written to you, as you are the first and uppermost principle in my life. I cannot even exist alone and I don’t want to be anything but a part of you or something together with you. Everything else seems meaningless to me and I am often completely desperate because what is essential is so impossible. It would take a miracle for me to be with you soon, and miracles do not exist!

My darling, I must finish now, as Friday evening supper is about to begin. It is always a beautiful and festive occasion here with us. On Saturdays we always have a proper religious service in our foyer. My mother is so radiant when the people from the home show up for the service. Hopefully, she may experience this joy for a long time to come. And hopefully, I’ll be able to confirm the receipt of a letter from you before too long.

A thousand kisses, darling

Your Valy

This is the first time Valy really talks about God, or religion. Her life focus, her desire to remain a doctor, nothing seems more important than Karl now—but is it really him? Or is it the idea that being with him will mean she has survived all this?

For Valy, the terror that has crept into daily life is set against her relief to finally be living alongside her mother in Babelsberg.

“Hopefully she may experience this joy for a long time to come”

is an acknowledgment of the deportations, of the unknown that hovers outside their door, the uncertainty that cloaks them, chokes them, even more than their cut-off emigration options.

More than half of Valy’s letters were mailed from “Bergstrasse 1, Babelsberg, Potsdam.” This was the address, from 1940, of her mother’s old-age home, where Valy would escape to, as often as she possibly could, and then where she finally was able to work herself in 1941. The district of Babelsberg itself was the center of the German film industry before—and after—the war, with the oldest large movie studio in the world, a neighborhood marked by wealth, comfort, and

prestige. And Potsdam, in general, is a bucolic, pleasant place, a royal suburb filled with palaces and gardens to wander in, relics of Germany’s aristocratic past.

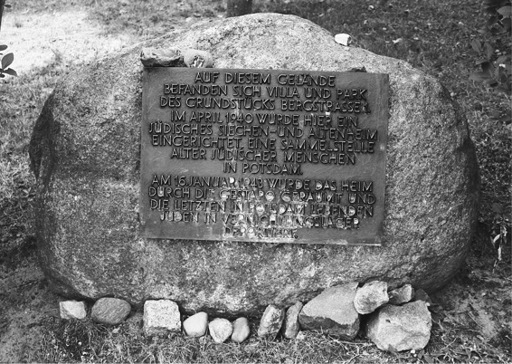

I find a photo of the villa Valy wrote from at Bergstrasse 1, and there I see the cupola Valy describes in her letters. The mansion was a massive, glorious structure, a mini capitol building; it had been the home of a wealthy Jew who successfully escaped, some years before Valy arrived in Berlin. It was located in what is now—and was then—a quiet, upscale suburb of large villas, a ten-minute drive from the tourist hubbub that makes historic downtown Potsdam a popular day trip from Berlin. In April 1940, Bergstrasse 1 became a Jewish infirmary and “almshouse” under the auspices of the Reichsvereinigung. On January 16, 1943, all the Jews of Potsdam were gathered at the house; most were sent to their deaths in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz and Riga.

I took the regional train from Berlin to Potsdam and then went by cab to the street that Valy wrote from for so many months. I knew there wouldn’t be much to see, exactly: the little palace she lived in had been destroyed, sometime in the 1970s. After the war, well after the conference that brought the three Allied powers together in Potsdam, even the street name, Bergstrasse, was changed, to Spitzweggasse, a combined memory suppressor as effective as anything I’d come across. No one I spoke to knew much, or anything at all, about an old-age home among the villas of Potsdam.

Online I read that—despite all the changes—there remained a tiny memorial on the site. When we arrive, I see the street is a dead end and there is no obvious memorial or marker at all, just a few quiet buildings and the woods beyond. I get out of the taxi and wander up and down the block, and the cabdriver and I are soon joined by a thirtysomething student and a sanitation worker, both of whom tell me that “if it’s about Jews, it’s long gone.” No one quite believes me when I say that the street name was changed or that there was once a nursing home here. But the driver, interested, perhaps, in someone

willing to let his meter run, remembers that, peculiarly, he has a 1928 map of the city in his car, and with it, we confirm that this was, indeed, once named Bergstrasse. With this odd stroke of luck, I am vindicated. In the end, it is the sanitation worker who finds the plaque, rusting and covered in lichen; it is nestled—half buried, covered in leaves and branches—in the ground, an homage to the small group-home of old people who clung to one another in the last years of their lives here.

At the spot, I add a stone to a small collection on top, and all the men go away feeling good that they helped this strange American find this strange

Denkmal

, or monument

.

Later, by regular mail, I receive a list of those living in the home in January 1943, provided by the Brandenburgisches Landeshauptarchiv, Oberfinanzpräsident, the Brandenburg State archives in Potsdam, and the financial archives that held all the indicators of Nazi looting during the period. It is among the papers I have requested

about Valy’s mother. All those who lived in the

Altersheim

Potsdam had birthdays decades before the turn of the nineteenth century—except for young Valy. All, surely, then, remembered a time when Jews were so well integrated in German life that their excision from that culture, and that life, would have seemed completely impossible, incomprehensible, as unlikely as our own separation from the lives we currently lead. Valy, by contrast, had known Germany to be only a place of incarceration, of separation, of desperation. Freedom was Vienna, Troppau, even—and the fantasy of America.

11-09-41

Darling,

Another week has come and gone, time is flying, so one grows quite dizzy, and still—it does not lead to the desired goal, at least not visibly and noticeably. My days are filled with work and cares and they pass in a jiffy. And yet, there is still no letter from you! Why do you always wait so terribly long before you write?! Darling, I have to ask you urgently to get me a visa for Cuba; and, if at all possible, also for my mother. I don’t know whether it still makes sense, but we have to try everything. Please get together all your and our friends. I hope they are not going to be stingy with their money. Don’t forget Dr. Friedmann and Dr. Huppert and/or their relatives. Regarding the various logistics etc. in connection with the visa, please contact Ruth Schnell, 1002 East 17th Street in Brooklyn New York. She is the sister of Elli Königsfeld who is the chief nurse of my former children’s station; she got the visa for her sister Elli and will surely be able to advise and help you. She is very competent and nice. Please make sure to contact her. We very much hope that sister Elli will soon be able to travel. Maybe you will also have an opportunity to speak with Elli’s friend or fiancé Dr. Proskauer. He is especially intelligent and fine. Last September he received a calling to NY University. But please, more than anything, do write to Ms. Schnell. And, above all, write to me!

Farewell, darling. I think often of you and of the time when I will be with you again. I know for sure that such a time will come. It is often so difficult for me in the present time with all its questions to believe in it and to get along here. But one is always reminded of that time—it does not let itself be repressed.

Please do write! A thousand kisses

Your Valy

Some had been able to get around the quota system by being named to posts at universities. Medical doctors could be “called,” as Valy puts it, as professors; it meant they were outside the visa system, they were “necessary.” It might have been possible in 1939. But November 1941? To Cuba? Even if Germany had not decided to close down emigration, this was nearly impossible at this point. The Cuba option had all but completely closed; the United States was suspicious of Jews using Cuba as a stopping point to America and had helped end Jewish emigration to the island. It was also increasingly, drastically, phenomenally expensive.

The U.S. State Department was of no help either. In November, Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long wrote in his personal diaries, quoting with approval the words of the (Jewish) American ambassador to Moscow, Laurence Steinhardt: “Steinhardt . . . took a definite stand on the immigration and refugee question and opposed the immigration in large numbers from Russia and Poland and Eastern Europeans whom he characterizes as entirely unfit to become citizens of this country. He says they are lawless, scheming, and defiant—and in many ways, unassibilible [

sic

]. He said the general type of intending immigrant was just the same as the criminal Jews who crowd our police court dockets in New York and with whom he is acquainted and whom he feels are never to become moderately decent American citizens.” In a month, the United States would enter the war

and make the conversation moot. But in the last weeks of Valy’s efforts to get out, there was little movement at the higher diplomatic levels of the U.S. government—even for those who were “someone”—and Valy was no one, really, of import.