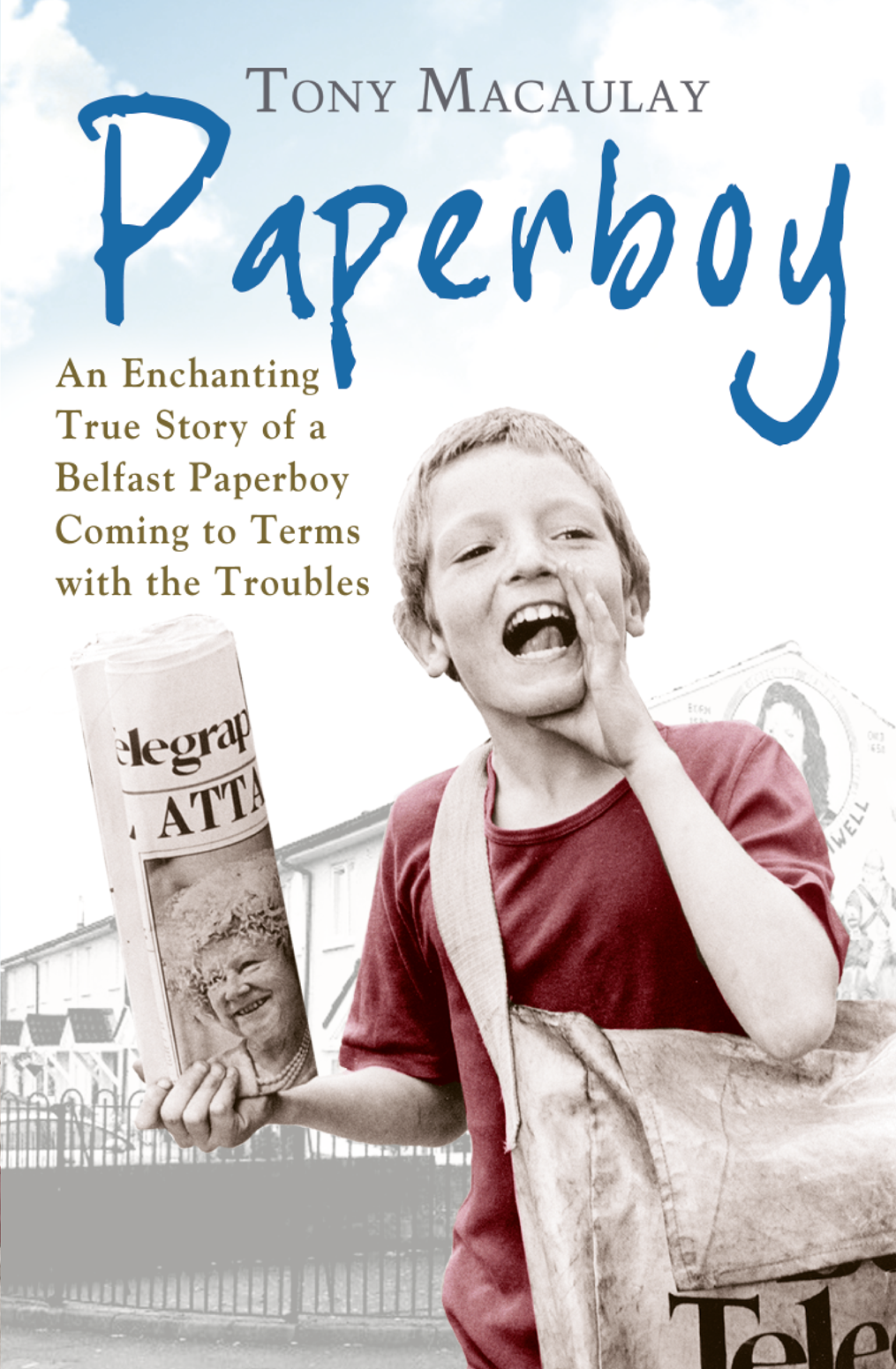

Paperboy

Authors: Tony Macaulay

Tony Macaulay

Paperboy

An Enchanting True Story of a Belfast Paperboy Coming to Terms with the Troubles

Contents

Â

Â

This book is dedicated to my parents, Betty and Eric Macaulay, their good friends, Ella and Harry Maguire, and all the voluntary youth leaders who kept young people off the streets and safe in Belfast in the 1970s.They are the unsung heroes of the Troubles.

I

was a paperboy. This never made it to my CV. So, just for the record, the dates of employment were 1975â1977. The place was Belfast.

I delivered the evening

Belfast Telegraph

â forty-eight

Belly Tellys

each night in the darkness. Belfast in the seventies was like the newspapers I delivered. Everything was black and white, albeit Orange and Green. Everything got smudged and ruined, like dark ink from the stories that dirtied my hands every day. But there were chinks of colour too, like in the weekly glossy magazines I provided to the more affluent customers of the Upper Shankill.

I was a paperboy. Aged twelve. Thin and easily crumpled. Blown around the streets by greater forces. More smart than tough. Yearning for peace, but living through Troubles.

And yet, as you will learn in these slightly less fragile pages, I was happy with my calling. I was a good paperboy. I delivered.

Chapter 1

Recruitment and Induction

I

was too young, so I was. You had to be a teenager to be a paperboy for Oul' Mac. He gave my big brother the paper round in our street when he was thirteen. By the time I was twelve I was jealous of the money and the status. I couldn't wait an extra year to get my foot on this first rung of the employment ladder. So one wet Belfast night I persuaded my brother to introduce me to Oul' Mac and to inform him of my eagerness to enter his employment.

My first job interview was a nerve-wracking experience.

âHave you any rounds going, Mr Mac?' I asked. (You never called him Oul' to his face.)

âAye, alright,' said Oul' Mac, âbut no thievin', or you're out!'

I concluded that my application for the post had been successful. He hadn't even asked if I was thirteen yet, so I didn't have to tell lies. Lies were a sin back then.

So, at the age of twelve, I set out on my career as a paperboy. My fear of age exposure gradually dissolved as I approached my thirteenth birthday, when I would become completely legit. I no longer had nightmares about being arrested by the RUC for underage paper delivery.

No sooner had I taken up my new position than my big brother decided that paper rounds were only for wee kids and he summarily left the arena of newspaper delivery entirely to me. I did nothing to dissuade him. I was delighted. Now the papers would be my exclusive territory. My wee brother was still more interested in Lego and Milky Bars and

Watch with Mother,

but I could sense that he envied my new career and was longing for the day when he too could follow in the family tradition.

Oul' Mac liked me. He said I was a good, honest boy. This was important to him. It meant you wouldn't steal the paper money that you collected from the customers on a Friday evening. He was a tough boss, though. He sacked wee lads all the time. Half our street had been sacked by Oul' Mac. But if you did a good job, with no cheek to the pensioners and no thieving, he didn't shout at you much and your position was secure. Oul' Mac had been a newsagent on the Upper Shankill for decades: no one could remember anybody else ever delivering the papers up our way. But he was getting on a bit now. Oul' Mac smoked and said âf**k' a lot. Of course, most men smoked and said âf**k' a lot, but Oul' Mac did both, simultaneously and ceaselessly. He was a thin man with no beer belly to hold up his tatty trousers, so he was always hoisting them up in between cigarette drags. I never saw him smile, but sometimes his eyes twinkled and I couldn't work out whether he was coughing or laughing. On these rare occasions when his mouth opened wide, I would worry for his last few wobbly, yellowing teeth, teetering on the brink.

Oul' Mac had dark yellow fingers, where the nicotine of ten thousand cigarettes blended with the printing ink of a million newspapers. His skin was dark and leathery because he was outdoors most of the time, filling and emptying his van. His face and arms were also a yellowy hue. Mrs Mac said he was bad with his liver. He had only a few remaining tufts of hair, mostly white, but in places the same dark yellow as his stained hands. His hair always stood upright, gelled in place by the binding glue of a million magazines on his fingers.

Oul' Mac's van had also seen better times. It was the same shade of dirty yellow as his hair and nails, apart from the rusty red bits around the bottom that sometimes fell off when it went over security ramps. The van spluttered around our puddled streets every day, the exhaust pipe just about hanging in there. Whenever you went outside, Oul' Mac's Ford Transit was always there on the street, like dogs and marbles and soldiers.

I would wait at the end of our street every night for the van to arrive. You heard the roar as it struggled up the hill in the distance, sounding like some part might drop off at any moment, in the titanic struggle between gravity, tons of paper and the failing power of an ageing Ford Transit engine. But Mac always made it, even in the snow when you hoped he wouldn't so you could have snowball fights with the other paperboys. Even through the barricades, when you feared his temper might get him hurt as he told the paramilitaries to f**k off and give his head peace.

Often the papers were late and the reason was right there in the headlines â dark words on grey pages. I seldom read the

Belfast Telegraph

, though. It was full of charmless men talking about âthem and us', and depressing bombs and killings, and why it was all the other side's fault, and, sure, I was living in the middle of the whole thing anyway. I was more interested in tips and TV and bonfires and music and outer space and Sharon Burgess. Sharon Burgess was lovely. I fancied her, so I did. She was my first sweetheart. I wanted her to be my own personal Olivia Newton-John.

Showaddywaddy were in the charts and the tartan tones of the Bay City Rollers played on the radio. Dad enjoyed the blonde one in Pan's People dancing on

Top of the Pops

, when the Osmonds from America were No. 1 and couldn't get to the BBC in London, where Harold Wilson with the pipe was Prime Minister. Elvis was getting fatter and I was getting taller.

We bought our first colour TV on hire purchase, complete with miraculous push buttons to switch between the three television channels. In

Blue Peter

on BBC 1, Valerie Singleton, John Noakes and Peter Purves showed me how to make an

Apollo

spacecraft from toilet rolls and silver milk-bottle tops. I wept when Freda, the

Blue Peter

tortoise, didn't make it through the winter in a cardboard box held together by sticky back plastic.

Then came our first black-and-white portable TV, clunky and bright red, with a handle on top. My big brother would use it to watch

Little House on the Prairie

in secret in the sitting room (hard men were not supposed to care about the trials of Laura Ingalls). Meanwhile, my wee brother would watch

Romper Room

on UTV, waiting excitedly for Miss Helen to see him through her magic mirror and say his name at the end of every programme. My granny kept a tally of Irish-sounding names, to check if Miss Helen was seeing more Catholics than Protestants.

It was the electrifying age of

Doctor Who

with the long scarf who travelled in the TARDIS through time and space to save the universe. The

Thunderbirds

blasted off from Tracy Island to save the world, and Ian Paisley shouted a lot down a microphone at the City Hall to save Ulster.

My mother watched old people in a pub on

Coronation Street

on UTV, and fancied Tom Jones when he sang âThe Green Green Grass of Home' on BBC 1. The appeal of both was lost on me. I rarely pushed the BBC 2 button, but my father did and he watched long documentaries and

Monty Python's Flying Circus

, laughing hysterically when the posh Englishmen wore dresses, talked in high-pitched voices and did silly walks. The family was safe and happy, and everyone was still alive, apart from my other granda.

Parallel trousers were the fashion statement to die for, and tartan turn-ups and trouser legs were savagely shortened to every shin on the Shankill. Platform shoes were all the rage, and you would sprain your ankle for the sake of style when you jumped a fence and landed awkwardly in dog's dirt after raiding old Mr Butler's orchard, even though your mother had told you to âleave the poor oul' fella alone because he was bad with his nerves'.

The Co-op Superstore in town was always on fire, while the chippy down the road was always open. Familiar smells were the hint of Tayto Cheese & Onion crisps on the breath, the whiff of vinegar from warm fish suppers in fresh newspapers, and an aromatic mix of Brut aftershave, Benson & Hedges cigarettes and burning double-decker buses that often hung heavy in the air.

For me, those years followed a familiar pattern, punctuated by School Term, Summer Holidays, the Eleventh Night, the Twelfth of July, Hallowe'en and Christmas Day. The changing seasons diverted my attention from pencil sharpeners to candy floss, from flags and bonfires to sparklers and Santa. Every week followed a well-trodden path too, like an experienced paperboy doing his rounds. School started again every Monday, Scouts was on Wednesdays,

Top of the Pops

was on Thursdays, the Europa Hotel got blown up on Fridays, the Westy Disco was on Saturdays, and on the seventh day I had to have a bath and go to Sunday school.

Life was action-packed and fast-moving, like an episode of

Starsky and Hutch

. We had thirty-minute school classes and five-minute bomb warnings. One minute, I would be in the classroom learning about the transverse section of an earthworm and the next I was in the playground learning about girls and perfecting the lead guitar section of âBohemian Rhapsody'. If I wasn't being good by having a jumble sale for the Biafran babies or going to âwee meetin's' to sing songs about Jesus, then I was being bad by bullying a wee ginger boy with National Health glasses or going to discos with rock-and-roll songs about sex and drugs and other things I didn't know how to do.

But as soon as I was employed, all of these distractions melted into the background of my existence. Being a paperboy took top priority. It was my vocation, so it was. Oul' Mac had discovered me. He had entrusted me with a great responsibility, and I was determined to fulfil the potential he had clearly discerned in my candid blue eyes, skinny four-foot frame and stringy, straight black hair.

Every night when Oul' Mac arrived in our street with the papers, he would fling open the double doors at the back of the van and jump up inside to dispense both papers and judgement. We paperboys held our collective breath. This was Oul' Mac's stage and if a customer had complained or if your paper money hadn't added up, a gritty drama would unfold. I witnessed several summary sackings at the van doors, when the guilty faced the humiliation of having to hand over their paperbags in front of their former colleagues. Oul' Mac would snatch the bag roughly from the dirty-handed guilty one, who would then run down the street, telling him where he could stick his paper round.

Your paperbag was an important tool of the trade. Actually, it was the only one. On my first day, I was handed a clean white canvas bag, strong enough to hold a hundred

Tellys

. As my career progressed, the ever-darkening colour of my bag was a testament to my level of experience as a paperboy.

On my first night Oul' Mac handed me a database of my customers. It was a list of street numbers scrawled on the back of one of the dirty wee paper sweetie bags he used for the humbugs he sold in the shop.

âThis is my mission if I choose to accept it,' I thought, imagining I was an American spy being sent out on

Mission Impossible

. I followed the numbers on the dirty wee paper bag as seriously as any secret agent hoping to crack a code to stop evil Russians from trying to take over the world. I criss-crossed the streets between odd numbers and even numbers, identifying target letterboxes and then launching paper missiles through them.

Some customers had impressive shiny brass numbers screwed onto their front doors, while others had simply painted their house number on a gatepost with some white gloss paint left over from painting the skirting board in their hall. Some of the houses had lush botanical gardens, while others had paved over the grass to park a motorbike. I learned that some gates were there to keep dogs and small children in and must always be closed, while other gates were for impressing the neighbours or just for swinging on.

On my virgin paper round, I was tentative and careful, just feeling my way. It was my first time, so I jumped no fences and closed all gates. It took me a while to work out exactly how to fold the paper and insert it correctly into the letterbox.

I smiled at all my customers, even at the ones who scowled back, like Mr Black from No. 13, who felt compelled to comment: âThey'll be delivering your paper in a pram next!'

I wanted to develop good customer relations from the outset. I met Mrs Grant from No. 2 at her front gate. She was just back from the shops with a bagful of pigs' trotters from the butchers and a prescription from the chemist for her Richard's throat. I opened her gate and offered to carry her shopping bags.

âOch, thank you, love,' she said, âI'm late for the dinner and my Richard's in bed with his throat.'

âI'm the new paperboy,' I proclaimed proudly.

âOch, that's lovely, love. Close the gate after you,' Mrs Grant replied.

I could tell we were going to have an excellent customer/supplier relationship. My mind was already drifting towards an assessment of Mrs Grant's tip potential. My big brother said the good tippers would tell you to keep the change, while the âstingy bastards' would expect every last halfpenny, even at Christmas.

My first few papers were awkwardly folded and ended up a little torn around the edges, but by the time I had delivered my final

Belfast Telegraph

on that first night, I had become nearly competent. The last newspaper of the night was withdrawn from my paper bag, folded perfectly and delivered swiftly within a mere ten seconds.

As I bounced away from No. 102, I heard the door unbolt behind me, and then the voice of Mrs Charlton with the Scottish accent calling: âOch, that's great, love. Don't forget my

Sunday Post

â and will you bring my bin round the back on a Wednesday, and I'll give you 10p for a wee 99 from the poke man?'

Mrs Charlton had âgood tipper' written all over her.

I knew already that I was going to be great at this. My hands were so black now that I had smudged the writing on the dirty wee paper bag Oul' Mac had given me. I would need this vital source of information with me for the rest of the week, by which time I would have committed all my odd and even numbers to memory. It was like learning algebra, but with a purpose.

When I got back to our house after my first paper round, my mother was in the living room on the sewing machine, making another dress for a swanky lady on the Malone Road. Mammy was always sewing for someone, and she had the very latest sewing machine from the Great Universal Club Book. It was so expensive she was allowed to pay it off over sixty weeks instead of the usual twenty.